May 2, 2020 marks 15 years since the passing of Greenpeace co-founder Bob Hunter. Although Hunter remains legendary within Greenpeace lore, readers may not know about his life outside of Greenpeace or the social-change philosophy that inspired his ecological strategy.

Hunter was born on October 13, 1941 in St. Boniface, Manitoba, the French district of Winnipeg in Canada. Young Bob rarely saw his war-veteran father, and then one day he was gone. Curiosity about his absent father’s war experience led Hunter to World War II books, and these books inspired the young man to write his own fantasy adventures.

The writer

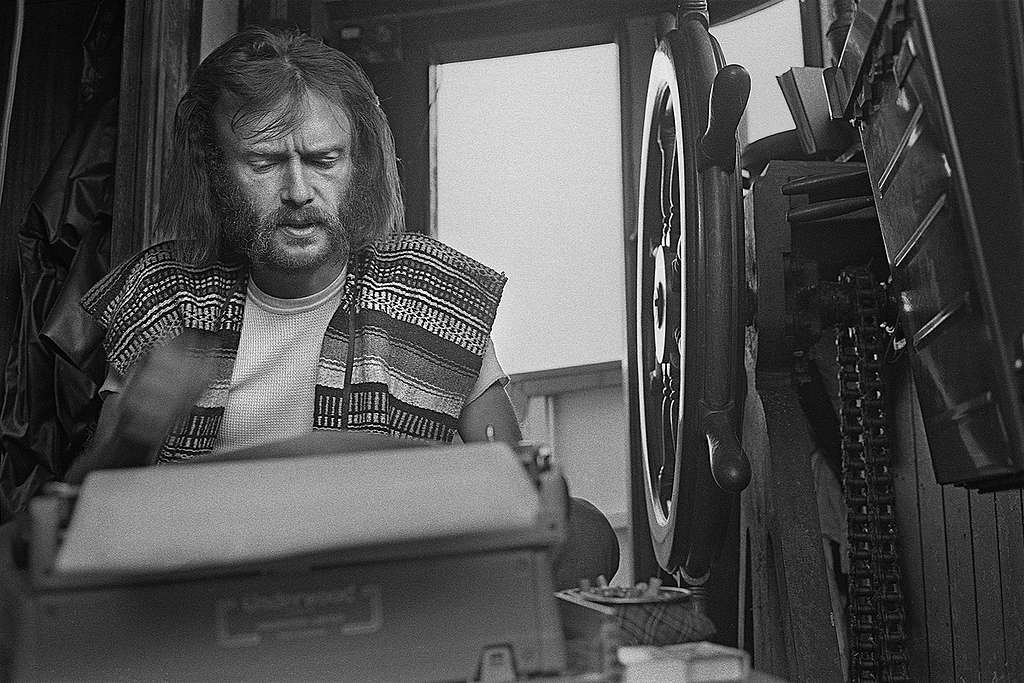

By the age of 14, Bob had filled ten thick notebooks with handwritten science-fiction stories. His mother bought him an Underwood typewriter for his fifteenth birthday, his most treasured possession. He wrote a 75-page story called “The Long Twilight,” in which a boy is kidnapped by a flying saucer and ends up alone in the universe. Twenty years later, on Greenpeace ships, Bob still pecked at the typewriter with two fingers; the fastest two-finger typist I’ve ever met.

At 17, Bob wrote “After the Bomb,” a futurist novel about a post-nuclear-holocaust civilization. He quit high school and left Winnipeg with his beloved typewriter to see the world. He made it as far as Vancouver, lived on hot dogs and water in a skid row hotel, began a coming-of-age novel, ran out of money, and hitchhiked back to Winnipeg. “The world’s shortest world tour,” he would later recall.

While working as a copy boy at the Winnipeg Tribune, an editor asked, “Who wants a byline?” Hunter raced across the newsroom and stood at attention. “Hunter,” said the editor. “Of course.” The assignment, a skydiving story, required that he leap from an airplane, which he did, but on landing he seriously injured his back. Decades later, Hunter would describe his chronic back pain as, “my reminder of the karmic consequences of ego.”

At 20, he travelled to Paris and London, where he began what would be his first published novel, Erebus, a searing, dark farce about finding love while working at an abattoir. In London, he met Zoe Rahim, a member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Hunter’s Bohemian writer life path turned sharply towards politics. Zoe took him to Speaker’s Corner, where he heard Bertrand Russell expound on pacifism, and to the historic 1963 peace march to Aldermaston.

They married, flew to Winnipeg, where their children, Conan and Justine, were born, and then to Vancouver, where Bob got a job at The Province, as a copy boy. When Erebus was published and earned a Governor General’s Award nomination, Hunter moved up to news reporter at the Vancouver Sun. When the editor ran a contest for a vacant columnist job, Bob won and began writing his own column.

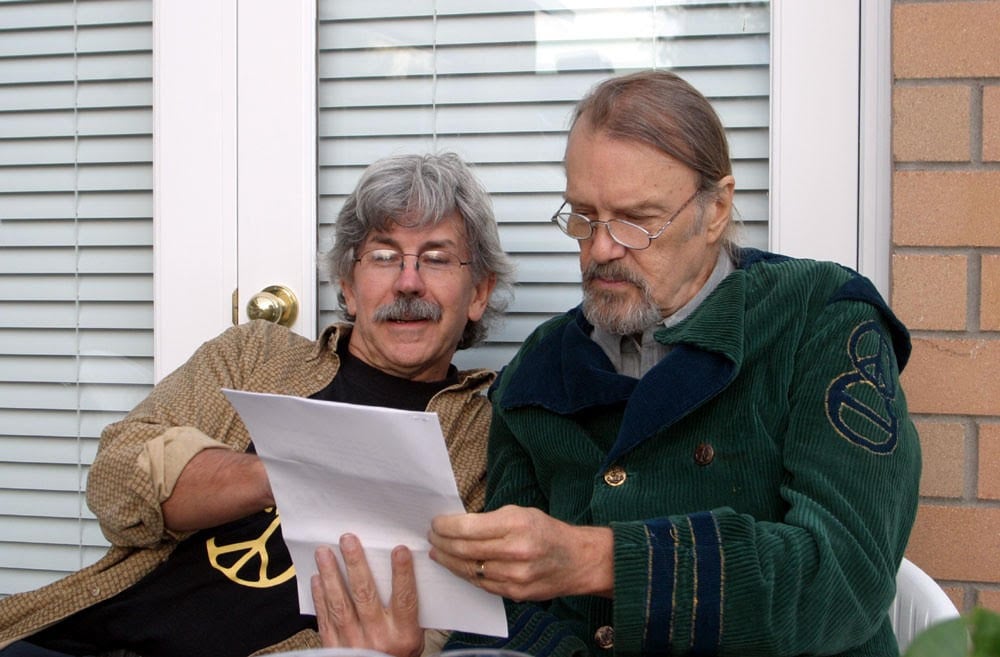

I arrived in Vancouver from the US as a war resister and got a job as journalist and photographer at The North Shore News. Bob Hunter’s columns seemed to me like the most interesting writing in Vancouver, so I phoned him, and we met at the Press Club, a small, unadorned pub on Granville Street. We arrived around 4pm and closed the pub down after midnight. Bob was a fascinating conversationalist, who listened as well as he spoke. He appeared brilliant. We shared a passion for advocacy journalism, peace activism, and the emerging science of ecology.

“Ecology’s the thing”

It is hard to imagine now, but in the late 1960s and early 70s, ecology was still a radical idea. There was no ecology movement, as there is today, no environment ministers, no ecology field trips in high schools, or courses in universities.

Bob had sailed on the first Greenpeace campaign (the group was still called “The Don’t Make a Wave Committee then) to protest the US nuclear test in Alaska, a tactic borrowed from the Quakers. Greenpeace was launching a second campaign against French nuclear testing. We had already learned that strontium-90, a radioactive by-product of the nuclear bomb tests, was appearing in the deciduous teeth of children around the world. This realization provided a key link between the peace movement and ecology.

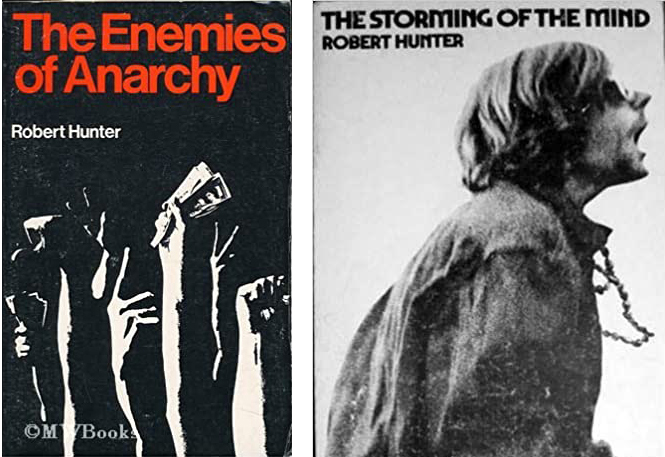

Bob had written an analysis of cultural change, and ecology, “The Enemies of Anarchy”. The “real anarchists,” he believed, were militarized elites, who ran selfishly about the planet, ignoring the laws of nature, devastating environments. The “enemies” of this institutionalized anarchy were the advocates for a new consciousness, for peace, unity, and ecology.

The necessary changes would not come from the political process, which was too slow and corrupted. Bob proposed that violent revolution “accomplishes nothing, except a changing of the guard.” Violence “diverts us from the real struggle, which is to attain a higher level of consciousness.” From Betty Friedan and the feminist writers, Bob had realized that the new consciousness would be more sensual than intellectual.

“Ecology is the thing,” Bob said. This new consciousness, he believed, arose from understanding natural relationships. “In nature,” Bob quoted from Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, “nothing exists alone.” The peace and civil rights movements recognized the whole human family, but this “whole” did not stop with the human community. We are all part of a much more fundamental ecological community. Furthermore, the necessary revolution is a spiritual journey because the Earth is sacred, and our relationships with all Earth’s creatures are sacred relationships.

In November 1969, the Cuyahoga River that runs through Cleveland, Ohio caught on fire due to massive chemical and oil pollution. “The rivers are burning,” I recall Bob shaking his head. “It’s Biblical. Humanity won’t endure a slow evolution of awareness.”

From the first time we met, Bob and I agreed that global society needed an ecology movement, and we spent the next decade together trying to make that happen.

Paul Shepard had described ecology as the “subversive science.” An honest understanding of ecology would change everything about human society. It was going to change our art, psychology, politics, science, and public discourse. Writers such as Carson, Shepard, Paul Ehrlich, Donella Meadows, Arne Naess, Gregory Bateson, and others were our mentors, calling for change. Someone had to make it happen, quickly, on a grand scale.

Mind Bombs

When I met Hunter, he had just written his second non-fiction book, Storming of the Mind. Bob had been reading Canadian media analyst Marshall McLuhan, who noted that electronic media (television and radio in those days) had converted the world into a “global village,” in which people could communicate from previously isolated regions, creating a “unified field of experience.” From McLuhan, Hunter had learned to think of the electronic media as a global nervous system, a “delivery system” for ideas.

Thus, Bob believed, it was not necessary or effective to think of revolution as an armed struggle. “Revolution these days,” he said, “is a communications struggle, a war of images. Instead of storming the Bastille,” he said,” we’re storming the minds of millions of people. Instead of lobbing bullets and bombs, were lobbing mind bombs, revolutionary images that will explode in people’s heads.”

To create an ecology movement, then, we had to come up with images that would circulate the globe, images that would inspire people to recognize their fundamental ecological nature, their kinship with every living creature on Earth.

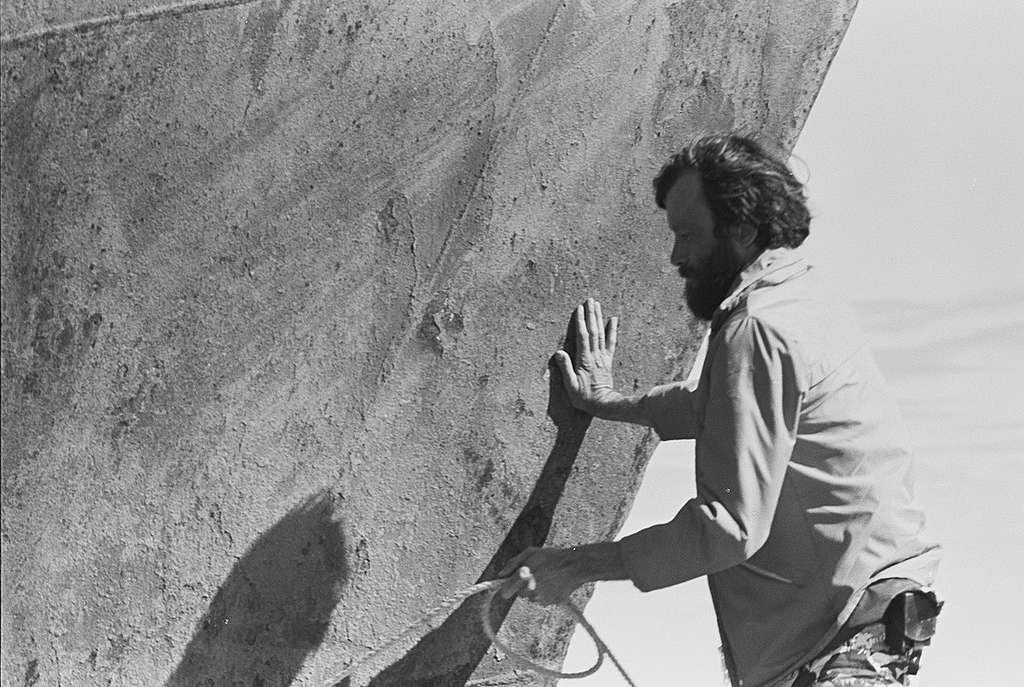

We staged actions around Vancouver, blocking toxic drain pipes into the Fraser River, and so forth, but the big idea that captured our imaginations came from cetacean researcher, Dr. Paul Spong in 1972: Save the whales! From that day forward, we formulated plans to take a boat into the Pacific, find the Russian and Japanese whaling fleets, blockade them, and record the confrontation on film for the world media.

Two-and-a-half years later, on April 27, 1975, we launched the 80-foot halibut boat, the Phyllis Cormack, Greenpeace V, from Vancouver, and in June we clashed with Russian whalers off the coast of California. The rest is Greenpeace history.

Latrine Officer

Bob often mocked himself, and the “hokus pokus” stuff, but he was deeply spiritual about ecology. Bob and I shared a passion for Buddhism (compassion for all sentient beings) and Taoism (nature as a model for human action). Bob believed that awareness itself was curative. With a deeper awareness of one’s own organic nature, a person could let the organism take over, without interfering, like the Taoists, trusting our instinctive wisdom to make decisions.

By 1976, Greenpeace had become famous. Money and support flooded in, and that changed everything. One day, during the second whale campaign, aboard the minesweeper the James Bay, christened Greenpeace VII, I watched Bob on the forward deck, alone, gripping a halyard, staring into the gray void of the sea. He wore the same white wool sweater and sandals he’d worn for weeks, but now a long scrub-brush dangled from his belt.

The pressure of holding the centre of this expanding movement and competing egos had driven him to the edge of sanity. The crush for a piece of the action, a spot on the crew, access to the budget, or for a share of the media notoriety had transformed a small cadre of ecology activists into something akin to a touring rock band.

Twenty Greenpeace offices now operated around the world. Even with supply lines and communication lines intact, which ours were not, the forward motion of a social movement can flounder on the delicacies of administering relationships.

Bob’s natural style was to include everyone. Yet, Bob, at the hub of an expanding movement, and not prone to authoritarian rule, suffered exhaustion and private anguish. We had been called “crazy” by more than one observer, but most of our antics were all in fun. The mystical side of Greenpeace did not imply a cult or collection of psychotics. We understood the importance of having a political strategy, a clear message, and a skilled team. But we also appreciated the value of a good myth and a good laugh.

The unique blend that had become Greenpeace – ecology, media awareness, spirituality, humour, and sea-going direct action – grew from a balance of myth-making and realism. However, by 1976, Bob appeared to be burning out like a meteor racing through the thick political atmosphere within the burgeoning organization.

His apparent madness on board the ship, however, concealed a method. Bob took seriously the advice from his mentor, the poet Allen Ginsberg, regarding power: “Let it go.” As a theatrical retort to the crush for power on the ship, and within Greenpeace in general, Bob had assigned himself the role of ship’s “latrine officer” and took to wearing the latrine brush, which now dangled from his belt as he shuffled about the ship. He could be found each morning in the latrine, cheerfully scrubbing away at the sinks and toilet bowls. To some, this was pure delirium, but his latrine officer act was a little internal mindbomb, not madness. “Don’t take yourself too seriously,” was the message.

Bob inspired people around him to contribute, made others feel essential. He was a natural leader, but not really cut out for internal politics. In 1977 he retired from Greenpeace to a rural life with his wife Bobbi and their son Will. Canadian journalism gladly took him back. Bob knew how to light up a public audience.

Time magazine later named Hunter as one of the “Eco-Heroes” of the 20th century. In 1991, he won the Canadian Governor General’s Award for his book “Occupied Canada: A Young White Man Discovers His Unsuspected Past“.

In 1998, doctors diagnosed Bob with prostate cancer and on May 2, 2005 he passed on. His ashes were scattered in northern Canada near the Arctic, at Tortuga Bay in the Galapagos Islands, and in Antarctica by his daughter Emily during the 2006 Sea Shepherd campaign against whaling. He is survived by his wife Bobbi; his four children Emily, Will, Conan, and Justine; and by a grateful Greenpeace organization, which owes to Hunter many of its fundamental principles and vision.

Links to Bob’s books:

Hunter, Robert; “Erebus,” 1968, McClelland and Stewart.

Hunter, Robert, “The Enemies of Anarchy: A Gestalt Approach to Change,” 1970, McClelland-Stewart; Viking

Hunter, Robert; “The Storming of the Mind: Inside the Consciousness Revolution,” 1971, McClelland and Stewart; Doubleday.

Hunter, Robert; “Warriors of the Rainbow: A Chronicle of the Greenpeace Movement,” 1979, McClelland and Stewart.

Hunter, Robert; “Occupied Canada,” 1991, McClelland and Stewart.