This month, Greenpeace celebrates 50 years of environmental activism, dating from the first campaign to stop a nuclear bomb test in Alaska, launched from Vancouver, Canada, on Sept. 15, 1971.

Several books published at that time inspired ecological awareness: Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, in 1962, the ground-breaking Limits to Growth by Donella Meadows, Dennis Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and their colleagues at the Club of Rome in 1972.

Still, ecology was not a fashionable idea in the early 1970s. Conservation groups protected parks, but there was no global activist movement giving voice to Earth itself. In the 1970s in Vancouver, a small group of people set out to create an ecology action movement on the same scale as the peace or civil rights movements.

Look it up

During the post-World-War-II nuclear arms race, a global peace movement gained momentum. In the US, biologist, Dr. Barry Commoner found traces of strontium-90, a carcinogenic byproduct of nuclear explosions, in children’s teeth. Similar studies in Russia and Europe revealed that radioactive nuclear byproducts contaminated every region of Earth. The peace movement and the ecology movement began to merge.

In the Eastern United States, Irving and Dorothy Strasmich (later “Stowe”) became peace advocates. In 1966, in opposition to the US war in Vietnam, they moved to Vancouver, on Canada’s west coast. They attended Quaker meetings, led peace marches, and supported Indigenous rights groups, and worked with Canada’s Voice of Women. (To learn more check out: Irving and Dorothy Stowe: Mentors to a movement.)

They met Bob Hunter, a columnist for the Vancouver Sun newspaper, writing about ecology, civil rights, and pacifism. Stopping war wasn’t enough, Hunter believed; we had to stop the destruction of the natural world. He told his friends, “Ecology is the thing.”

Jim and Marie Bohlen came to Vancouver to avoid the US military draft for their sons, Lance and Paul. They met the Stowes at a peace march and became friends. Meanwhile, 22- year-old Bill Darnell organized an “Ecology Caravan,” which toured the province.

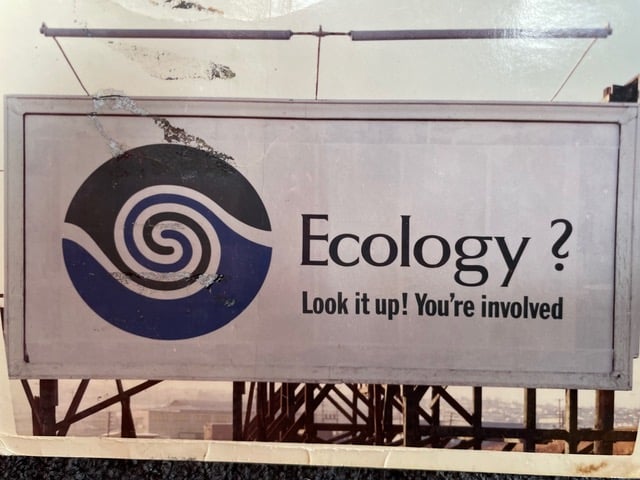

Hunter introduced the Stowes to journalists Ben and Dorothy Metcalfe, who had been so disturbed by forest devastation and bellowing smokestacks from pulp mills, that they placed 12 billboards around Vancouver that declared:

Ecology?

Look it up! You’re involved.

I was one of some 50,000 American draft resisters, opposing the Vietnam War, who slipped north into Canada between 1965 and 1973. In Vancouver, I soon met peace activists such as Hunter, the Metcalfes, and the Stowes.

A Green Peace

A single event united these activists. In November 1969, the United States announced a 5-megaton thermonuclear bomb test, scheduled for October 1971 on remote Amchitka Island, 4,000 kilometers northwest of Vancouver. The island was a US Wildlife Refuge for 131 species of sea birds. An earlier, smaller test had registered 6.9 on the Richter scale and killed wildlife around the island. The 1971 test was going to be five-times more powerful.

Bob Hunter wrote a column about the risks, proposing that the explosion could cause a tsunami on Canada’s west coast. For a demonstration at the US/Canada border, he created a sign, declaring: “DON’T MAKE A WAVE.” At the protest, Irving Stowe proposed a citizen’s group to halt the bomb. Early meetings included Hunter, Bill Darnell, the Metcalfes, the Bohlens, Deeno Birmingham with the Voice of Women, and radical activists Rod Marining and Paul Watson. Stowe suggested they name the ad hoc group “The Don’t Make a Wave Committee.”

The activists were familiar with a 1958 Quaker protest boat, the Golden Rule, that sailed from California to the Enewetak Island nuclear test site in the Philippine Sea. One morning, Marie Bohlen told her husband, “We should just sail a boat to Alaska.” That same day, a Vancouver Sun reporter called, asking what the new group might do to stop the test. Jim Bohlen blurted out, “We hope to sail a boat to Amchitka to confront the bomb.” Everyone loved the idea and set to work.

The Committee met at the Unitarian Church to discuss how they might find a boat and skipper willing to make the trip. As the meeting ended, Irving Stowe flashed the “V” sign, and said “Peace.” Bill Darnell replied quietly, “make it a green peace.”

This term, “green peace” articulated the merging peace and ecology movements, and stuck in everyone’s mind. In September 1971, the group launched the 64-foot fish boat, the Phyllis Cormack, skippered by fisherman John Cormack. For the protest voyage, the boat was re-christened as “Greenpeace.”

The US detonated the bomb before the Greenpeace ship was able to reach Amchitka Island, but the voyage created such an uproar in Canada, the US, and in Europe, that the US cancelled all future nuclear tests in Alaska. The following year, the Committee adopted the name that so perfectly articulated the emerging zeitgeist: Greenpeace Foundation. Ben and Dorothy Metcalfe took over leadership and launched a similar campaign against French nuclear bomb tests in the South Pacific. After three years of protests, France also relented.

The environmentalists in Vancouver had discovered the greatest inspiration for any social visionary: they could win.

All sentient beings

Some of us in Vancouver felt that we had to launch a campaign that would speak directly to ecology, that would give voice to all of nature’s beings. In 1972, Canadian author Farley Mowat met New Zealand brain researcher, Dr. Paul Spong, who was performing studies with a captured Orcinus orca (killer whale) at the Vancouver aquarium. Mowat told Spong that Soviet and Japanese whaling fleets were decimating the whales, and that the Atlantic grey whale was already extinct. Spong came to Greenpeace with an idea to launch a campaign to save the whales, using tactics similar to the anti-nuclear-bomb tactics.

Spong’s idea seemed perfect for our global ecology campaign. The whales needed help, and the campaign would give voice to the notion of ecology, looking after the Earth itself and all the creatures of the Earth.

We faced two critical obstacles. The nuclear tests had been held at fixed locations. The whaling fleets, on the other hand, moved constantly. We did not know how we might find them. Secondly, we would have to blockade moving ships and could not likely achieve this with the fish boat or a sail boat.

To solve the first challenge, Spong undertook an international espionage trip that led him to Sandefjord, Norway, where he gained access to International Whaling Commission archives and located previous routes of the whaling fleets. To solve the second challenge, we borrowed an idea from the French commandos, who had boarded the Greenpeace protest boat, Vega, in 1973. The French sailors had used inflatable Zodiac boats to chase down and board the Greenpeace boat. “That’s it,” said Hunter. The inflatable protest vessel has since become an icon of Greenpeace sea-going actions.

In April 1975, we set off on the Phyllis Cormack to find the whaling fleets. In June, we intercepted the Russian whaling factory ship Dalnyi Vostok, some 50 nautical miles west of California at the Mendocino Ridge sea-mounts, right where Spong’s maps suggested they would be. We confronted the whaling ships, and took photographs and 16mm film to document the encounter. A week later, when the film and photographs went out on wire services around the world, Greenpeace became recognized internationally.

We followed this campaign with efforts to save Harp seals and other marine mammals, to stop toxic dumping in the oceans, and to save forests. Friends of the Earth arose at about the same time, and within a few years, ecology groups were forming all over the world. At last, the world had an ecology action movement.

By 1977, public donations allowed colleagues in London, Susi Newborn and Denise Bell, to purchase the first ship that Greenpeace actually owned, an Aberdeen trawler, re-christened Rainbow Warrior. In 1979, we formed Greenpeace International in Amsterdam.

Fifty years after that first campaign ship departed from Vancouver for Alaska, Greenpeace now has national and regional offices throughout the world. The long battle to save Earth from ecological calamity continues.

The next fifty years

To imagine how we might make progress during the next 50 years, perhaps we should take stock of progress over the last 50 years.

We’ve witnessed 50 years of environmental activism; we have thousands of environmental groups, environmental ministers, environmental agencies, protected zones, legislation, scientific papers, warnings, data, conferences, government promises, and public outcry. We have millions of allegedly green products, sustainable processes, and eco-friendly corporate mission statements.

That might feel potentially promising, but we have to ask one simple question: Is humanity on Earth more sustainable today than we were in 1971?

The data reveals that the answer to this question is clearly “No.” We are not more sustainable in 2021 than we were in 1971. There is less biodiversity, more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, more toxins in our soils, less carbon in our soils, less fertile soil, more dry rivers and dead lakes, more ocean dead zones, less forest, more desert, more humans, a billion people living on the edge of starvation, and ever-greater human demands on all the dwindling resources. We are clearly less sustainable.

Since 1971, human population has more than doubled (from 3.76 to 7.67 billion) while vertebrate abundance has declined by over 30% and, collectively, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals have declined by 60%. Commercial fish stocks have been depleted by 85% and oxygen-depleted ocean zones have increased by 75%. We continue to lose about 13 million hectares of forests every year. Meanwhile, since 1971, human carbon emissions have increased by 250%, from about 4 to 10 Giga-tonnes/year.

So, to be honest, everything we have achieved is not enough. This implies a second critical question: So, what is enough? What do we have to do differently? Three years ago, I wrote a summary of my answer to this question, “What can we do?.”

My greatest concern for the next 50 years is that we risk misunderstanding the problem we face, and fail to make the necessary deep changes in consciousness and behaviour. For example, we have a robust climate movement and we’ve held 34 international climate meetings over the last 42 years, but our global carbon emissions keep going up. Our next important step may be to re-frame the challenges for the next 50 years.

We are facing much more than a climate crisis. We face a complex, global-scale ecological crisis. Climate disruption is one symptom of this crisis. Other symptoms include biodiversity collapse, fresh water depletion, nutrient cycle disruption, and the myriad other challenges, including war and social injustice.

Ecologists call our general crisis “overshoot.” Most successful species tend to overshoot their habitats. Evolution teaches species to reproduce and consume. Evolution does not teach species when to stop. Wolves overshoot watersheds, algae will overshoot the nutrient capacity of a lake, and locusts will overshoot their available food. We can witness overshoot in our gardens, or in the forest, where plants grow over each other, entangle with each other, and expand to and beyond the limits of their habitat.

Overshoot is natural, and the solutions to overshoot in the natural world all involve a contraction of the hyper-successful species. Whatever else we do over the coming decades, we will not likely solve our ecological crisis unless we contract our numbers and our consumption, especially the frivolous consumption in the rich nations. We need to address changes to our unnatural, unecological, and unjust economic system.

Some observers object, claiming that “there is no limit to growth,” or “no limit to human ingenuity,” but the lessons of the natural world tell us otherwise. Some extreme technology-obsessed billionaires imagine that we’ll colonize other planets and leave the depleted Earth behind.

I ask this question to myself virtually every day: How do we change the human trajectory, away from growth, chaos, and collapse? What path will lead us toward genuine sustainability? I suspect that our progeny — and all other species — will be far better off if we embrace our relationship with the living Earth, learn from nature itself, consciously contract, slow our economies, and allow wild, untrammeled natural habitats to expand.

References and Links:

“Irving and Dorothy Stowe: Mentors to a movement,” Rex Weyler, Greenpeace, August, 2021.

Rachel Carson, “Silent Spring,” Houghton Mifflin, 1962.

Donella Meadows, et al., Limits to Growth by the Club of Rome in 1972,

Rex Weyler, “Greenpeace: The Inside Story,” Raincoast Books, 2005.

William R. Catton, “Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change,” (University of Illinois Press, 1982).

“Earth Overshoot Day back to July amid post-pandemic emissions rebound,” inews.co.uk, 2021.

“Personal actions to address climage change,” Earth Overshoot org

Rex Weyler, “What can we do?,” Greenpeace, 2018.

“Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity,” J. Rockström, et. al., Ecology and Society, 2009.

William Rees, “The Way Forward: Survival 2100,” Our World, June 2012

“The Mining of Minerals and the Limits to Growth,” Simon P. Michaux, Geological Survey of Finland, April 2021.