“Human-induced climate change and the war on Ukraine have the same roots: fossil fuels and our dependence on them” said Ukrainian climate scientist Svitlana Krakovska as Russia, one of the world’s biggest oil and gas producers, was invading her country.

At the time, she was addressing The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change from her home in Kyiv, and had to withdraw from the approval session of the latest report as bombs hit her city.

A month later the war in Ukraine is now a humanitarian crisis: more than 3.7 million people who have fled the country, and roughly 13 million people are estimated to be unable to leave with limited access to food, water, and medical care.

Fossil fuels are fuelling the war in Ukraine

There’s a direct relationship between fossil fuels and the Russian war machine. Rosneft, one of Russia’s main petroleum companies, is reported to be one of the main suppliers of fuel to the Russian army. Rosneft also supplies petroleum to companies like BP. So every time Russian oil or gas are bought it’s not just contributing funds to the war chest, it may be keeping military machinery running. Rosneft and subsidiary company Rosneft-Aero and Transneft reportedly delivered fuel to the Russian Army before and during the invasion. [1]

To stop this war we need a global divestment from, and an embargo on, Russian fossil fuels as soon as possible, as well as urgent delivery of humanitarian aid to those in need.

Fossil fuels have a history with war

The struggle over energy resources has been a conspicuous factor in many recent conflicts, including the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988, the Gulf War of 1990-1991, and the Sudanese Civil War of 1983-2005. Greenpeace has spoken out about such conflicts in the past, especially during the last Iraq war.

The 1990 Gulf war was largely a conflict about oil. The issues which provided Iraq with the pretext for its invasion of Kuwait were oil pricing policies and oil revenues. Though oil was not the sole reason for Iraq’s actions, it was a powerful motivator for swift action from the United States and its allies who moved quickly to protect its own and OECD countries’ access to important oil supplies. And the large-scale exploitation of oil by foreign companies operating in southern Sudan has increased human rights abuses there and has exacerbated the long-running conflict in Sudan, resulting in two million people dying and four million displaced since 1983, as well as recurring famine and epidemics.

According to research in 2021 by Greenpeace Italy, Greenpeace Spain and Greenpeace Germany, almost two-thirds of all EU military missions monitor and secure the production and transport of oil and gas to Europe. The governments of Italy, Spain and Germany have invested more than €4 billion to protect climate-damaging fossil fuels since 2018.

Fossil fuel companies cannot be trusted

Early in the war in Ukraine, oil companies jumped on the opportunity to expand their operations, using a looming energy crisis as a reason to pedal their polluting business. Shell even bought oil from Russia after the invasion, and only apologised and pledged to cut ties with Russia after huge public backlash that could affect their bottom line. Now other oil companies such as BP and Total Energies promise to be divesting from Russia, after being directly linked to the Ukraine war.

Like big tobacco, these companies jump on any opportunity to keep selling their dirty products. Unless we continue to expose their dirty business model, they will continue to profit off conflict and climate crisis.

Fossil fuel trade is propping up an unjust system

To help ensure peace and stop the climate crisis, governments need to cut their dependency on fossil fuels and phase them out immediately. Today, the world economy is still running largely on fossil fuels which continue to make up for over 80% of the global energy mix.

This addiction to fossil fuels places energy security and climate action at the mercy of geopolitics. Governments cannot claim to stand for peace if they continue to finance war. And shifting from Russian oil and gas to oil and gas from other countries with questionable human rights records, like Venezuela or Saudi Arabia, will only shift geopolitical power from one abuser to another.

These power imbalances can lead to countries acting with impunity. At the recent COP26 global climate talks, leading oil and coal producers like Saudi Arabia and Australia stymied efforts to include fossil fuel phase-out in the final text, and countries like Russia and the United States are not members of the International Criminal Court which prosecutes war crimes.

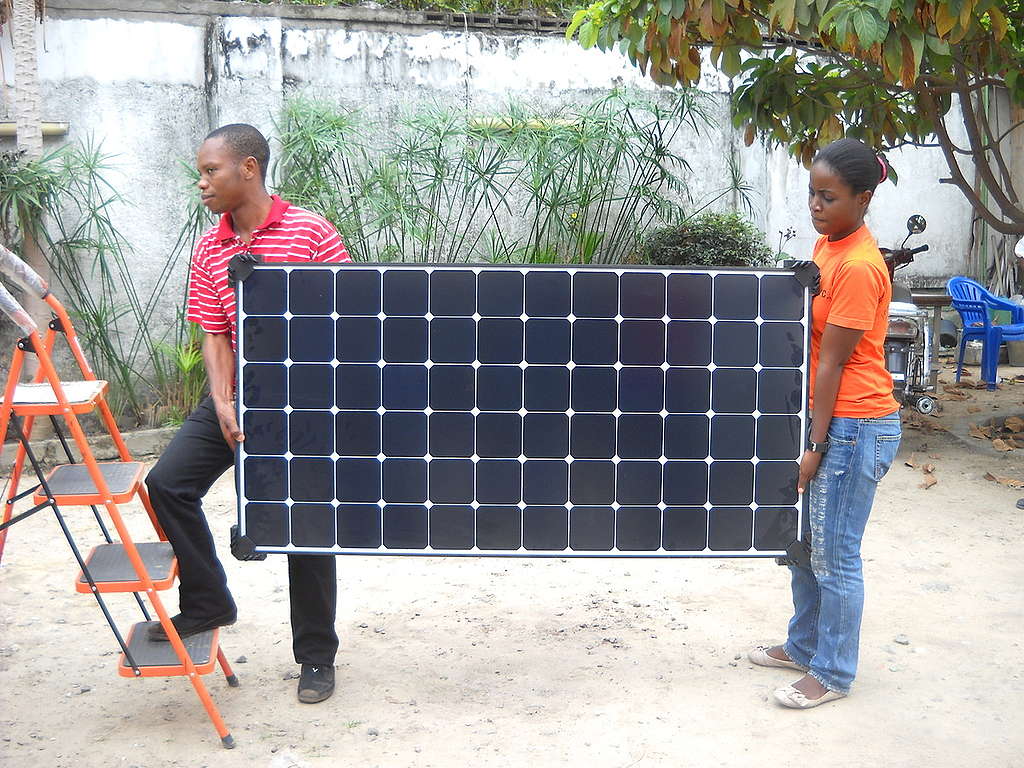

Renewable energy is a pathway to peace

In order to get to a more just and peaceful world, we need countries to cut their fossil fuel dependency. To transition quickly, wealthy countries must first reduce their energy demand and maximise energy efficiency. Then move fast to fill their remaining energy needs with renewable energy.

Unlike fossil fuels, renewable energy is less likely to feed geopolitical power struggles or inequality, as its infrastructure has the potential to be largely localised. This could in turn help to reduce trade with countries with questionable human rights records. Localised renewable energy could also help to protect consumers from price shocks like the global energy crisis we are seeing today.

Safeguarding energy security and the climate

The combination of renewable energy and energy efficiency is a better choice for energy security. If the potential of these two are combined, total global energy demand could be reduced by up to a quarter by 2030. Energy efficiency measures would account for half to three-quarters of the total energy savings, with renewables delivering the rest. This could have huge implications for safeguarding the climate, with fossil fuels being the number one contributor to global heating.

A fast and just transition to renewable energy is possible. Installing renewable capacity is much faster than building new fossil fuel infrastructure – In the UK it takes on average 28 years to develop a new oil well, versus two years to build a solar farm. And if the world invests in more renewable energy it will become an even cheaper, more viable option. Morocco and Egypt are rapidly scaling up their renewable energy capacity, and showing how collaboration can help everyone go farther and faster together.

This is a chance for governments to break the cycle of fossil fuel destruction and transition to a green peaceful future. Governments must act for peace and a safe climate with a transition to efficient and renewable energy as quickly as possible.

Marie Bout is Global Climate Communications Strategist at Greenpeace International

Reference:

[1] According to a 2017 report posted by the company in Russian, companies in the Rosneft group supplied the Russian Ministry of Defence, the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, the Russian Emergencies Ministry, the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Russian Guard and was at the time the sole supplier of motor fuels to the National Guard, which has since been deployed on the border with Ukraine.