For International Biodiversity Day, I preface an interview with Indigenous leader and rights activist Arkilaus Kladit with an exploration of the natural wonders nestled in the rich forests of New Guinea, and in particular its western region known as Papua in Indonesia. This island, the world’s second largest island after Greenland, stands as a major biodiversity hotspot.

Shaped like its native Bird of Paradise, the island is on the frontline of both the biodiversity and climate crises due to a relentless push by agribusiness companies, backed by international finance, that want to clear its forests to make way for palm oil, paper pulp, and other plantations. Indigenous Peoples across the island are engaged in struggles with outsiders and governments who underestimate the strength of Indigenous connection to land and choose not to value their right to forest-based economies that protect their cultural and natural heritage.

And what a heritage it is! The variety and ruggedness of the terrain has allowed for a flourishing of different cultures across New Guinea, with many hundreds of distinct languages across dozens of separate speech ‘lineages’. While Indigenous land management methods and traditions vary from place to place in New Guinea, in accordance with local ecological conditions, the common thread is Indigenous connection to land. This is why land rights are so important throughout the island, including in Papua. And indeed, there, all land is owned by someone – hence the phrase Papua Bukan Tanah Kosong (Papua is not an empty land).

New Guinea is also like a treasure chest filled with a kaleidoscopic array of distinctive animals. Besides birds of paradise, the island’s treetops are home to reclusive marsupials – gliders, various species of tree kangaroos; and the furry cuscus family, including the critically endangered blue-eyed spotted cuscus.

Down on the forest floor giant cassowary birds roam, and four species of Echidnas – egg-laying mammals – raise their puggles (babies). One of these Echidna species has been named after much beloved nature broadcaster, David Attenborough.

Perhaps less cuddly, although no less impressive, crocodiles and giant 2.5 metre monitor lizards that rival the length of the famous Komodo Dragon are also to be found – and unlike dragons, these are at home up in trees! There is also a wealth of bats, snakes, frogs, crabs, fish and insects along with many other classes and orders of animals besides. Because of the inaccessibility of much of New Guinea’s ecosystems, scientists are sure that there remain many more species that they have yet to ‘discover’ and describe.

When it comes to plants, the island of New Guinea really outshines. In 2020, a hundred botanists working together announced that the island was home to 13,634 species of plants. That’s more than any other island on Earth — exceeding the famous mega-diversity of Madagascar. What’s more, two in three of New Guinea’s plant species are found nowhere else on Earth. This in turn allows for an amazing range of ‘food landscapes’ – Indigenous food systems that are both healthy, and serve to reproduce unique cultural ways of being.

Knasaimos-Tehit Indigenous People

Arkilaus Kladit is an Indigenous leader and rights activist who lives in Papua’s Bird’s Head – the westernmost tip of the island. Arkilaus shares an insight into what land and forest means for his Knasaimos-Tehit Indigenous People in Southwest Papua Province, Indonesia.

“The forest is a precious gift that has been passed down to us through generations, an asset that sustains our way of life. We are dedicated to preserving it, as it holds everything we need – from animals to medicinal plants, from our daily necessities to the places for our sacred ceremonies and traditions. Our connection to the land is deep and profound, it holds us like a mother’s womb. It is a part of us that we cannot abandon – we cannot leave our mother behind, no matter how far we may roam.

Money is just a tool that helps support our lives, but we can survive without it as we have access to food and enough resources for our daily needs.

Our rituals are sacred and enduring, and they will never die out because they bring blessings and connect us to our ancestors. Each of our clans has their own traditions and ceremonies to ask permission from our ancestors for permission and guidance. These show us how to responsibly use the land, from cultivating food gardens to finding the timber to construct our homes, as well as guiding us on which areas are designated off limits as ‘Sasi’ for protection and regeneration.

We are very worried about the way the central government makes decisions regarding our land as if we do not exist, treating the land as if it were vacant. This lack of legal recognition for our land worries us greatly and leaves us feeling very afraid that harm will come to us. It is essential for the Knasaimos-Tehit people to be officially recognised by the state to ensure that our rights are respected. Recognition would empower us to safeguard our land and forest and would ensure that anyone wishing to use the land must first seek our permission, effectively preventing unauthorised access and protecting it from destruction.

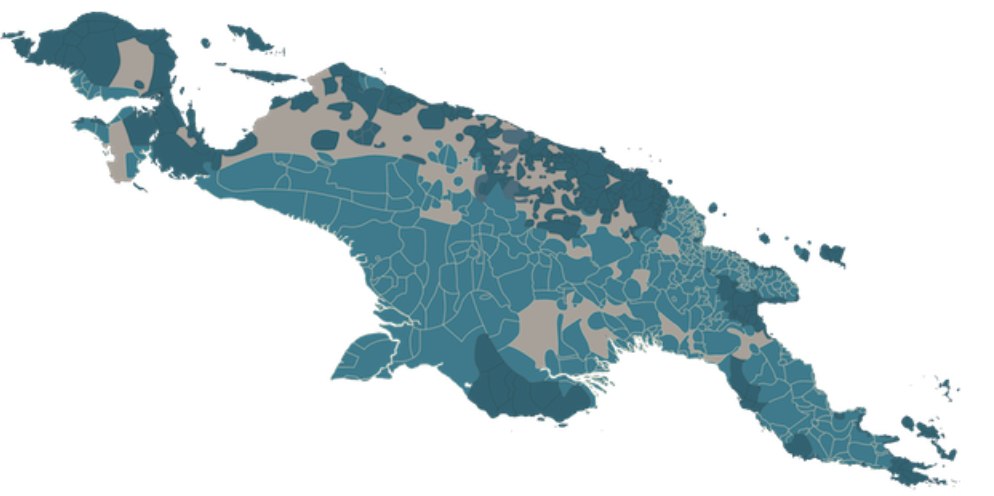

But our goals go beyond securing a government regulation that legally recognises our Indigenous land rights. We are committed to educate and motivate everyone to understand the irreplaceable nature of our land and forest and that we cannot buy and sell it, helping everyone understand the importance of allowing us and future generations to manage and protect the land. To this end, with the help of our NGO friends we are learning how to map each family clan’s land, and submitting these maps to get legal recognition.

In the past, young people and women had limited roles in forums under our traditional practices, but times have changed, and they are now involved in all activities. We strive to continue that improvement, increasing our capacity to sustainably manage the land on a scale that effectively meets our basic needs.

Our deep bond with the Knasaimos forests and with nature is profound and intrinsic, we are a part of it, and the forests are our lifeblood, woven into the fabric of our existence.”

Igor O’Neill works on research and communications for Greenpeace Indonesia’s forest campaign