N.frəˌstrʌk.tʃə Infrastructure. If you’d rather snort pepper up your nose and squirt lemon in your eyes than read more about this dreary economic term – you’re probably not the only one.

Any movie scripts about infrastructure? No. Any songs, hiphop, jazz, poems? No. It’s a word thoroughly devoid of intrigue, romance or passion.

Well, gird your loins folks, from May 14th – Budget Day – we’re going to have to forgive infrastructure for being the world’s most boring word, and fall in love. Why?

Infrastructure may well save our lives, as well as our livelihoods.

When the economists start talking, we should probably get past that Homer Simpson voice in our heads ( “blah di blah blah donuts”) and pay the “infra” some serious attention.

In the last three months, the capitalist world has done a spectacular volte-face on public spending.

Neo-liberalism with it’s pitiless austerity, already starting to look shabby and unfashionable at the start of 2020, is languishing in the dumpster of expired economic doctrines.

Fiscal restraint is out. Big Government is in again.

And New Zealand, like most other developed countries, is about to bet the bank (the Reserve Bank) on a massive spend up, counting on the Keynesian “multiplier effect” to revive the economy.

The most popular item on any trend-conscious Finance Minister’s shopping list?

You guessed it.

Infrastructure.

Narrowly defined as the basic systems or services that a country uses to work effectively, many people imagine transport, water pipes or energy – ie: public works.

Remember high school history – the New Deal, Franklin Delano Roosevelt spending his way out of the Great Depression in the 1930’s. The Hoover Dam. The Lincoln Tunnel.

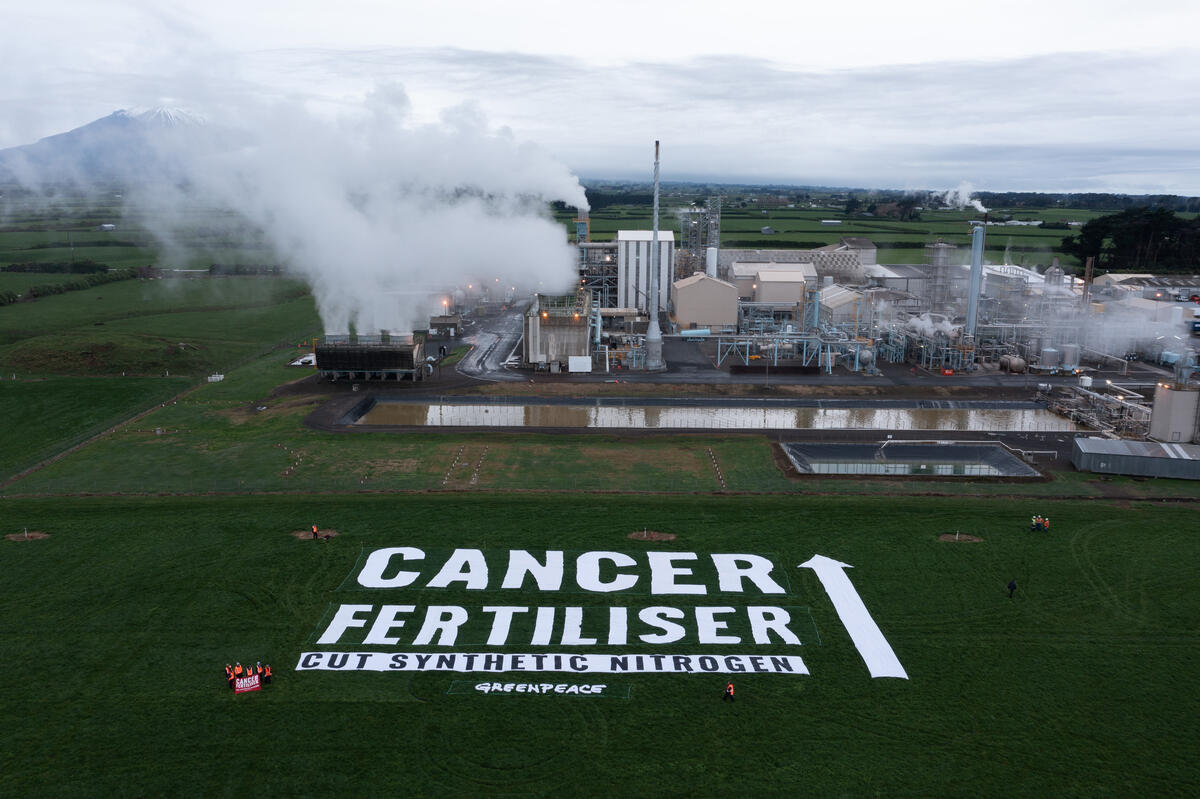

And closer to home, Robert Muldoon’s think-big projects of the early 1980’s, Glenbrook Steel Mill, the Kapuni Urea plant and the Clyde Dam.

Spending up large on traditional infrastructure in that context might have made eminent sense.

You create new jobs, inject money into the economy that multiplies as it gets banked again and again. Then, as a bonus you get something bright and shiny to show off at the next OECD meeting, like a nice new dam.

Only, this time round, at this juncture of the anthropocene, things are different.

As well as the crucial employment opportunities, what we build with those Government billions, what we actually create, is not just a nice-to-have – it is critical to our future. It may dictate that future, and more pointedly, decide whether we actually have one.

No pressure Grant.

This awful pandemic is the crisis in everyone’s faces right now, but Venetian dolphins and urban birdsong aside, nature is still on the brink. The climate crisis hasn’t been upstaged and walked off in a huff. It waits for us, close by, dressed in black on a horse. Sorry but there you are.

If we don’t want to stumble out of one existential crisis and into the next, perhaps we need to expand the definition of infrastructure.

In one dictionary the term is described as the basic framework of a system, an underlying foundation. Another way to think of infrastructure is the platform upon which we work and play. It seems entirely ludicrous to build such a stage without being fully cognisant of the earth upon which it stands.

Jobs are jobs you might say. Well not really. There are two kinds of jobs. There are those on projects that return us to business as usual and effectively take us backwards. These belong to the eras of Muldoon and FDR.

In order to weather this recession and avoid walking straight into the next storm, we need to consider the second type of jobs. We must think beyond factories, dams, roads and tunnels.

We must prioritise projects which offer genuine transformation. Like what? Well try these ones outlined in Greenpeace’s Covid Recovery Plan.

At its most basic, it means no new roads and plenty more rail, busways and cycleways.

It means a set of bold and transformative investments to support farmers and food processors to shift to producing regenerative, organic and plant-based foods.

More solar panels, wind turbines, and warm, dry homes.

And yes, for sure, the basics still need to be done. But why not tackle them and improve our strained relationship with nature at the same time? That’s value for money.

We know that New Zealand needs a major upgrade to our drinking water and wastewater systems. But we need to think beyond pipes and public works.

The Government Inquiry into the Havelock North gastro outbreak found that protecting the source of drinking water provides the first and most significant barrier against contamination and illness.

Investing in water Infrastructure looks like restoring wetlands, fencing streams, planting riparian corridors to help prevent farming run-off getting into our waterways. It helps purify water cost-effectively, while providing numerous co-benefits in the form of cleaner lakes and rivers, more fish and healthier streams.

Investing in the protection of forests, wetlands and stream margins also acts as a barrier to natural disasters like floods and landslides – a form of natural insurance.

Such vision requires courage, daring and a certain amount of imagination.

It also requires new ways of describing what we want. Take the much-used expression “shovel-ready” for example. It conjures up images of sturdy men in hard-hats, jackhammers at the ready.

Ideally that’s just a language issue and we’re not going to see the vast majority of money ploughed into male-dominated work. That would be a massive fail.

The reality of the Covid economic crisis is that women’s jobs are going to be more affected than men’s, not less. Simply because women are overrepresented in the hospitality, retail and tourism industries.

Women are already in a more economically precarious position than men, earning significantly less on average, especially if they are Māori or Pasifika.

In New Orleans, research shows two-thirds of the jobs lost after Hurricane Katrina were being done by women. But the recovery created jobs mostly in construction and rebuilding – traditionally male-dominated fields. A whopping 83 percent of single mothers were unable to return to New Orleans for two years because there simply wasn’t work for them.

The recession brought on by the pandemic appears to have more in common with a natural disaster than something like the Global Financial Crisis or the Great Depression.

Whether it’s by accident or design, many infrastructure spend ups in the past have been characterised by a seamless handshake between male-heavy occupations.

Not only would an old-school infrastructure package do a disservice to the majority of New Zealanders looking for jobs, it would, by definition, lack the necessary imagination and courage to envision a better world, safe from climate change and ecological breakdown.

Let’s build back better.

And maybe we can start with the language. Rather rather than “shovel-ready”, let’s fund projects which are climate-ready, future-ready. Ready for the future we want – the future we need.