The world’s leading climate scientists have just released their assessment of the climate emergency and ways to deal with it. It’s a crucial report delivered at a moment in time when governments are taking stock of their action under the Paris Agreement.

And in short, the verdict of the scientists is this:

“There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all (very high confidence).”

“Rapid and far-reaching transitions across all sectors and systems are necessary.”

“The choices and actions implemented in this decade will have impacts now and for thousands of years (high confidence).”

Let that sink in for a moment.

The Synthesis of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report forms a robust analysis of thousands of peer-reviewed research papers published over the past decade, with more details to be found in the underlying six reports.

Here are our ten key takeaways from the report:

1. Human-caused climate change is widespread, rapid and intensifying

Human-caused climate change is now affecting weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe. Impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people have been widespread.

Effects on ecosystems are more widespread and with further-reaching consequences than anticipated. Half of all species are already on the move, due to climate change affecting their environments. Further, evidence of observed changes in extremes such as heatwaves, heavy rain, droughts and tropical cyclones, and, in particular, their attribution to human influence, has only strengthened.

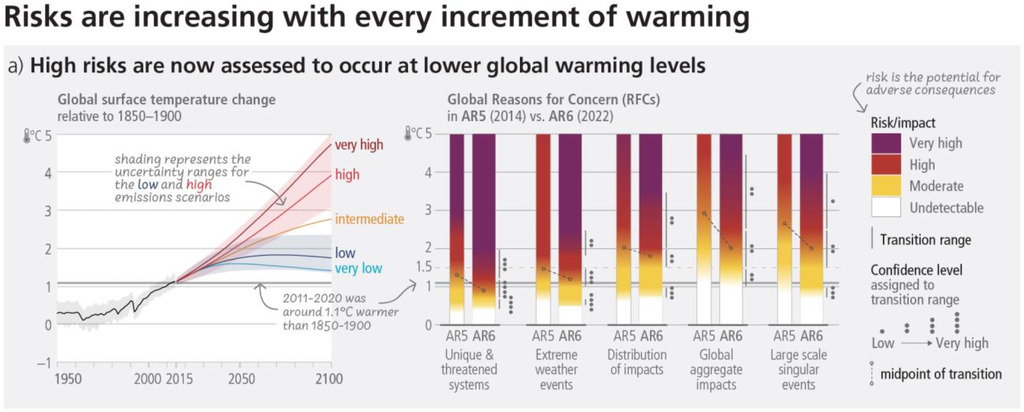

2. Impacts and risks are appearing faster and will get more severe sooner

The global aggregated impact and risk levels are now assessed to become high to very high at lower levels of warming than previously assessed.

Currently, we are at around 1.1°C of average global warming and heading towards about 3°C.

Unique and threatened ecosystems are expected to be at high risk already in the very near term at 1.2°C, due to mass tree mortality, coral reef bleaching, large declines in sea-ice dependent species, and mass mortality events from heatwaves.

At just 1.5°C, up to 14 percent of species assessed in terrestrial ecosystems will likely face a very high risk of extinction. Reaching 1.5°C will bring more and worse heat extremes and dangerous heat-humidity conditions, extreme rainfall and associated flooding, tropical cyclones, wildfires and extreme sea-level events.

Between 1.5°C–2.5°C, risks associated with large-scale singular events or tipping points, such as ice sheet instability or ecosystem loss from tropical forests, transition to high risk.

At about 1.9°C warming, half of the human population could be exposed to periods of life-threatening climatic conditions arising from the coupled impacts of extreme heat and humidity by 2100.

3. Those least responsible for the climate crisis are hit the hardest

Vulnerable communities who have historically contributed least to the climate crisis are most affected. Nearly half of the world’s population live in regions that are highly vulnerable to climate change. Between 2010 and 2020, human mortality from floods, droughts and storms was 15 times higher in highly vulnerable regions, compared to regions with very low vulnerability.

At the same time, only 10 percent of the wealthiest households contributed up to 45 percent of global consumption-based household GHG emissions.

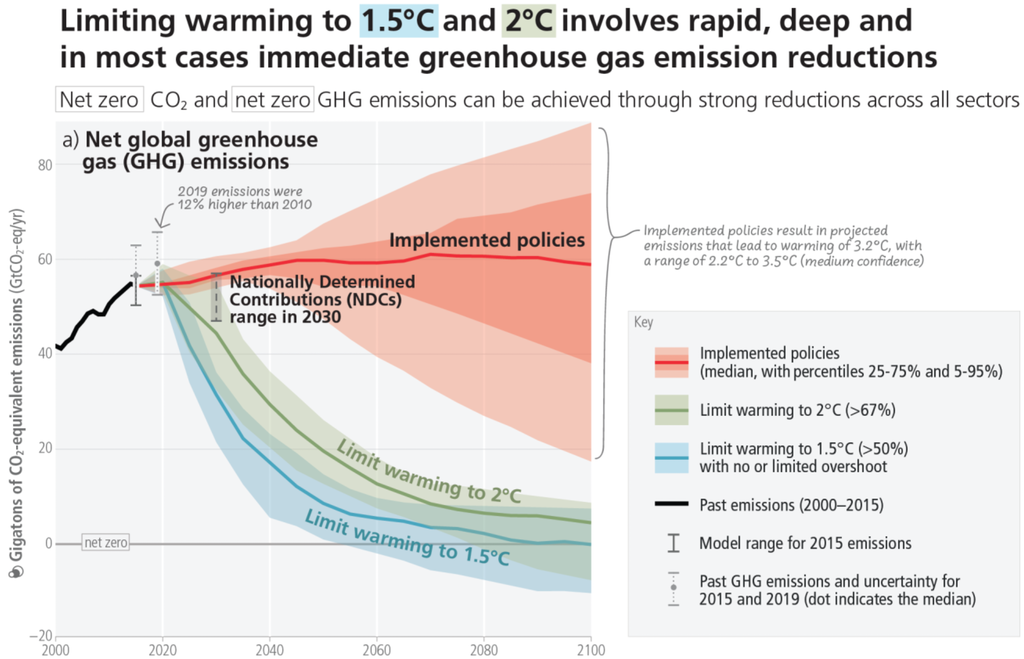

4. We’re on track to high and very high risks and no decline in global emissions

With policies implemented by the end of 2020, we are on track to about 3.2°C warming by 2100. Instead of halving global emissions by 2030, which would be required for respecting the Paris Agreement warming limit, there would be no decline in global emissions by 2030.

5. With urgent action, the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal is still within reach

With continued emissions, we’re on track to reach around 1.5°C in the near term. But it is still in our hands to halt warming there to avoid the most severe impacts. By following the strongest IPCC emission reduction pathways, warming would peak between 1.4°C and 1.6°C and by the end of the century be below 1.5°C.

So, with urgent action, the Paris Agreement’s long-term temperature goal is still within reach. This would require roughly halving global emissions by 2030, followed by net zero CO2 by around 2050, and achieving and sustaining net negative CO2 (and GHG) emissions globally thereafter, with annual rates of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) being greater than remaining CO2 emissions.

However, while some carbon dioxide removal is necessary, the technologies behind it carry many uncertainties, and hence, the reliance on it should be limited.

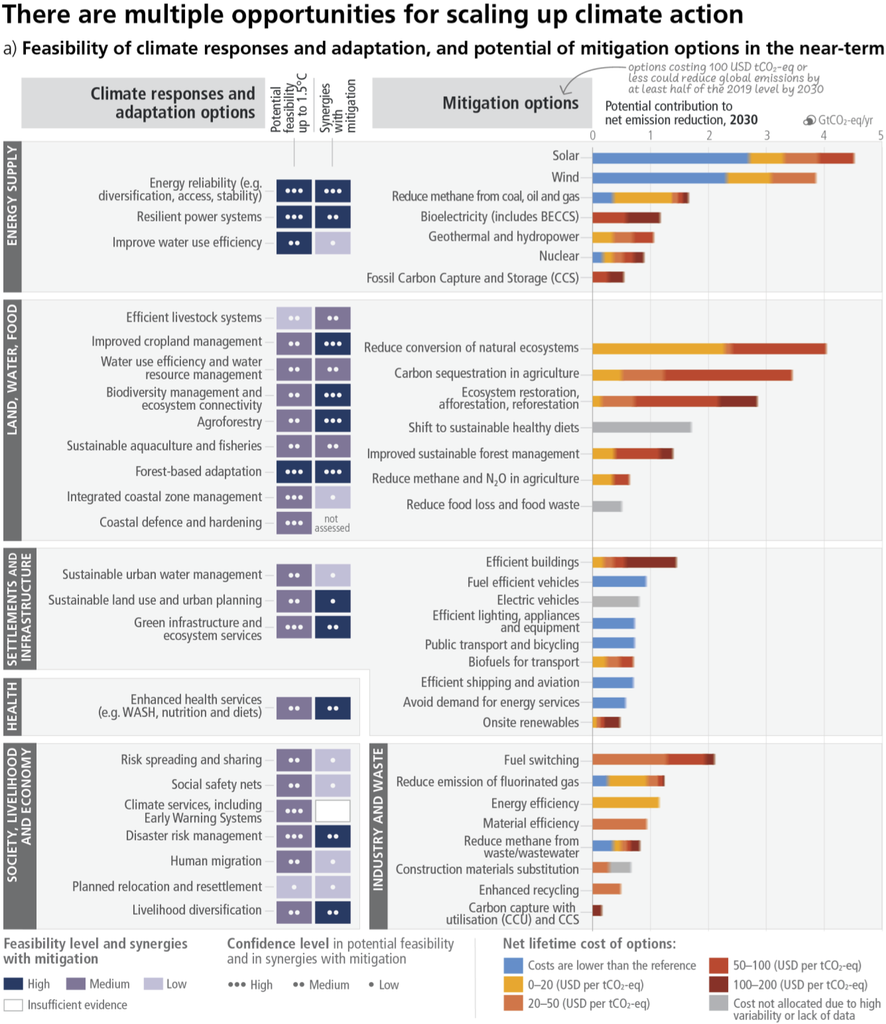

6. This is the defining decade and we have all the solutions we need

We have all the tools we need for at least halving global emissions by 2030. Half of this mitigation potential is estimated to be low-cost or even to come with cost savings. The biggest contributions would come from solar and wind energy, protection and restoration of forests and other ecosystems, climate-friendly food systems, and energy efficiency in its many forms.

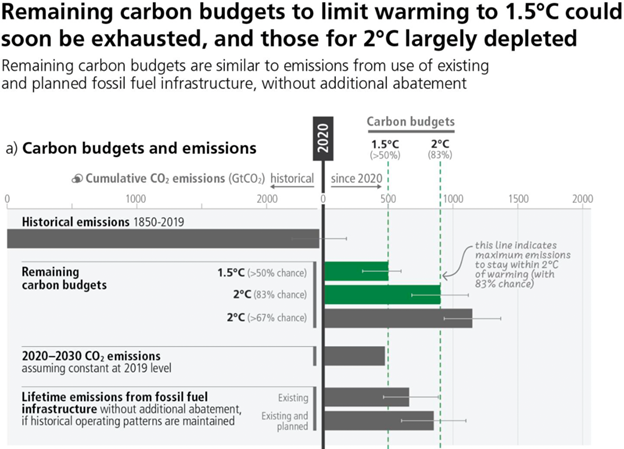

7. Fossil fuel exit needs to be fast: The infrastructure we already have is too much

The fossil fuel infrastructure already in place is enough to exceed the 1.5°C warming limit, if allowed to be in use without further restrictions. Hence, there is no room for any new fossil fuel infrastructure, and what exists needs to be phased out early, as is illustrated by the graph below.

In other words, keep it in the ground:

“About 80% of coal, 50% of gas, and 30% of oil reserves cannot be burned and emitted if warming is limited to 2°C. Significantly more reserves are expected to remain unburned if warming is limited to 1.5°C.” (SYR longer report)

8. Solutions must deliver in real life, not only in models

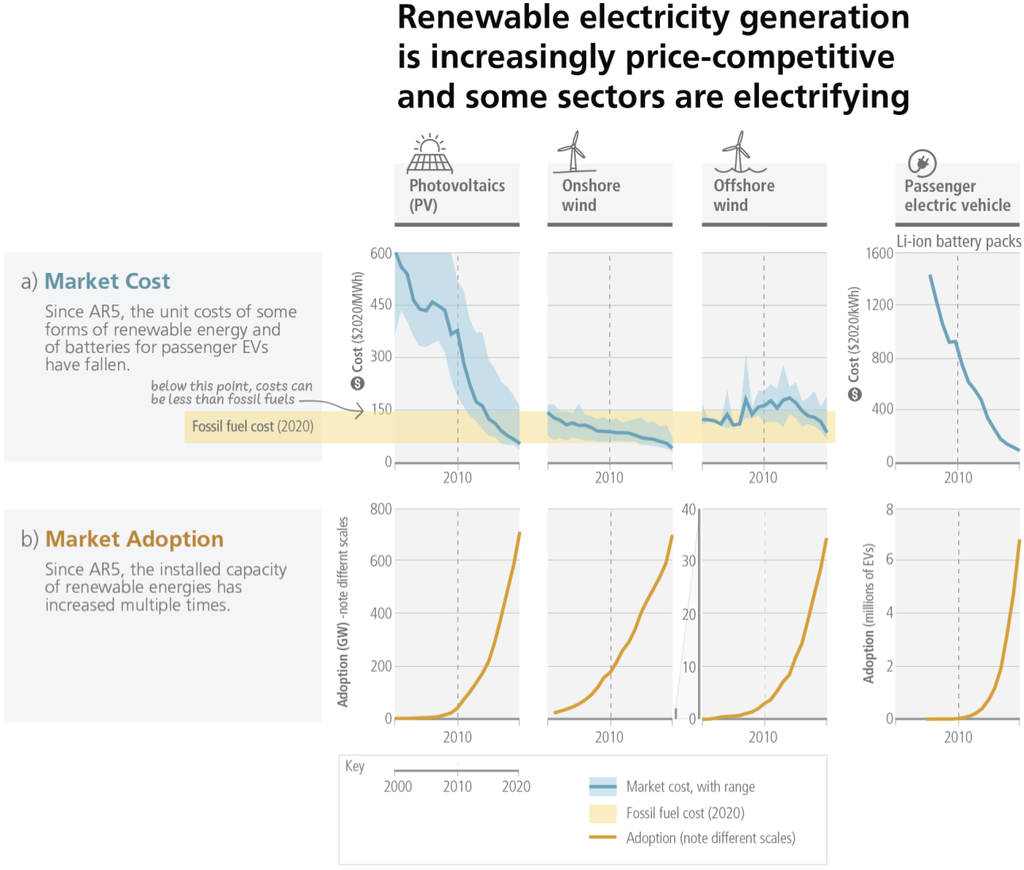

Among the big game-changers since the previous assessment is the breakthrough of solar and wind, that are now reaching cost levels equal to or below those of fossil fuels, being ready to enable the decarbonisation of different sectors. These developments have occurred much faster than anticipated by experts and modelled in previous mitigation scenarios. It is a game-changer.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) has not made significant progress. It plays a big role in many emission reduction models, but still fails to deliver at scale in real life. Technological carbon dioxide removal, where CO2 is captured directly from the atmosphere (DACCS), or from biomass energy (BECCS), also play a role in most mitigation models, but remain unproven at scale, and they come with many feasibility and sustainability constraints.

Carbon dioxide removal solutions that maximise sustainability benefits and minimise risks should mean working with nature and for communities, such as reforestation, restoration of ecosystems or soil carbon sequestration in agriculture. This is critical in order to avoid conflicts with other land use needs or creating large environmental impacts and conflicts with human rights and food security.

9. Delivering on equity, social inclusion and finance is fundamental

The scale and speed of transformation needed will not be possible without equity and social justice, both between and within countries. According to the IPCC, integrating climate action with macroeconomic policies can support sustainable low-emission development paths, safety nets and social protection, and improve access to finance for low-emissions infrastructure access, especially in developing regions.

At the heart of equity considerations is finance. There’s enough money in the world to enact real change. But today, public and private finance for fossil fuels are still greater than those for climate adaptation and mitigation. According to the International Energy Agency, last year alone, the oil and gas industries earned a whopping 4 trillion USD with businesses fueling the climate crisis!

The annual investment requirements before 2030 are a factor of three to six greater than current levels for mitigation alone, with the largest needs being in the developing world. On an international level, equitable solutions need to be found that meet the adaptation and mitigation needs and address loss and damage for those least responsible.

10. From incremental to transformative change, in all sectors, with all hands on deck

There’s a rapidly narrowing window of opportunity to implement climate resilient development. We need to think beyond individual technologies, sectors and actors. Instead, we must adopt holistic, inclusive and transformative approaches that encompass both mitigation and adaptation.

Protecting and restoring our biodiversity is fundamental. According to the IPCC, maintaining the resilience of biodiversity and ecosystems at a global scale depends on effective and equitable conservation of approximately 30 percent to 50 percent of Earth’s land, freshwater and ocean areas, including currently near-natural ecosystems.

To achieve “rapid and far-reaching transitions across all sectors and systems” we need strong policies and international cooperation. It’s all hands on deck and those with most responsibility and capability need to lead the way. This goes for governments, businesses, investors and high-income individuals alike.

So now what?

Scientists have delivered their toolbox for survival. Now it is our job to make sure the science is acted on, by governments, businesses, investors and citizens. And that we make it personal.

We must make the right choices, and with great haste.