Alarm bells have been ringing with increasing volume. The United Nations, governments, humanitarian and environmental organisations, scientists, and journalists – all have issued dire warnings regarding the fate of the FSO Safer, an abandoned oil storage vessel currently at anchor off the Red Sea coast of Yemen with a cargo of more than a million barrels of crude oil. The dangers to human life and the environment are clear – a major leak or an explosion from the FSO Safer would be devastating to the people, wildlife, fisheries and ecosystems of the Red Sea.

The Safer, a giant tanker relic from the oil-heady days of ultra-large crude carriers, is 360 metres long, 70 metres wide and is anchored in the Red Sea about 8 km from Ras Isa in Yemen. It contains an estimated 1.1 million barrels (over 140,000 tonnes) of crude oil.

The single-hulled tanker, previously called Esso Japan, was built in 1976 and sold to the Yemeni government in 1988. It was last surveyed in 2014 by the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) but has not been inspected since because of the continuing Yemen war. It is now ‘out of class’ meaning it is no longer insured. After seven years of neglect, its hull is rusting, generators have stopped and fire-fighting equipment is not working.

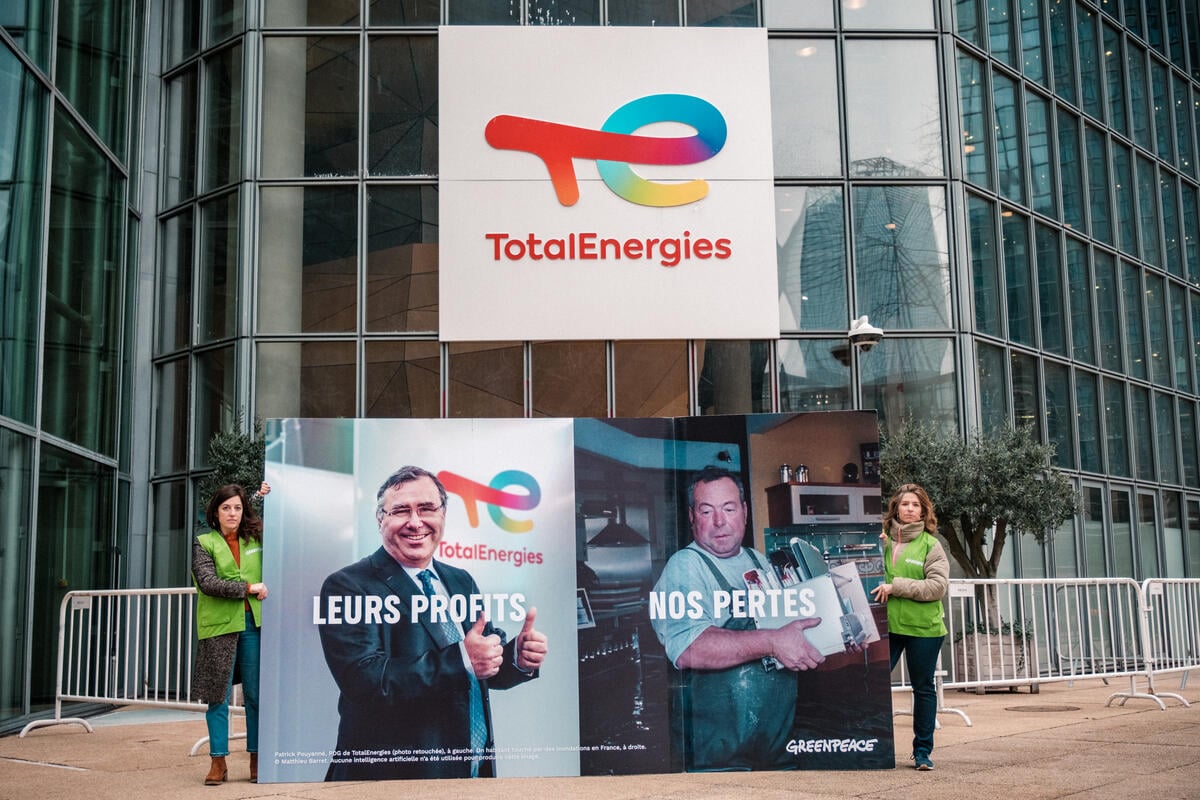

Greenpeace recently issued a briefing highlighting the potential humanitarian and environmental impacts of a major oil spill or explosion on the Safer. We welcome the recent announcement that an agreement has been reached to get the oil transferred from the Safer to another tanker, but meanwhile, the ship remains in a serious condition and the lack of preparation for a potential major spill continues to be a grave concern.

Greenpeace has called for the deployment of an oil containment boom around the Safer as a first line of defence and for other oil spill response equipment to be in the region on stand-by.

People also need protection

Oil is a poisonous inflammable liquid that contains toxic and carcinogenic chemicals, which can attack the liver and kidneys, the nervous and blood systems.. Skin can absorb oil, and the fumes and smoke from burning can seriously damage the lungs. Breathing the vapour or mist can cause headaches, dizziness, drowsiness, and nausea and may lead to unconsciousness.

When a spill happens the natural response of communities is to get out and do whatever they can to try and clear up the mess. However, oil washing up on a shore is a dangerous situation for the environment, and for anyone who tries to help. Trying to clear it up is extremely difficult, dangerous and stressful work that requires the use specialist protective equipment and a secure place to safely store huge amounts of oily waste.

Anyone – volunteers and professionals alike – participating in oil removal will be exposed to the oil and any toxic fumes. Gloves, protective clothing and suitable masks are needed to minimise inhalation and skin contact with both un-weathered and weathered oil, including oil deposited on the shore as “tar balls” or “tar patties”. Appropriate hand hygiene and washing facilities including suitable cleaning detergents need to be available to clean incidental skin exposures.

Unfortunately, it is very likely that the kind of equipment needed will not be widely available, which leaves the local population seriously exposed. Hence, in addition to oil spill response equipment, it is vital that stocks of personal protective equipment be made available at strategic locations on the coast.

If protective equipment (overalls, gloves, boots, face masks) is not available, the strong advice is not to go on or near a contaminated beach. In case of fire, the elderly, children and people with heart or lung problems should keep well away from smoke or haze.

Small coastal fishing communities are likely to be the most severely impacted, fishing is likely to be impossible and fisherfolk will be exposed to oil vapours. The oil will contaminate boats, risking further exposure. Long-term contamination of fishery resources will be inevitable, although the scale and extent of such contamination are dependent on weather and sea conditions, and difficult to predict.

Huge amounts of hazardous waste are produced when removing oil from beaches – often around ten times the amount of oil spilt. What this means for the Safer if all the oil were to spill it is likely to result in 10X140,000 tonnes – almost one and a half a million tonnes of toxic waste.

Domestic waste facilities are not suitable for such high volumes of toxic waste and would be rapidly overcome by these amounts. And while this problem is significant, it is vital that the situation is not made worse by trying to burn the waste without thorough evaluation of the situation, as this can generate toxic smoke which spreads the airborne pollution and may leave it difficult to remove residues.

The following suggestions (in arabic here and here) are based on best practices on oil response strategies. It is essential to coordinate with local authorities and oil response professionals.

What to do in case of an oil spill

- Immediately report where oil is coming ashore, and length of coastline affected.

- Ensure children, vulnerable people, livestock and any pets are kept away from contaminated areas.

- In case of air pollution, stay inside, close windows and doors, wash fruit and vegetables before eating, if available make use of air conditioners if they keep out particles.

- Coordinate with oil response professionals and other local authorities

- Use personal protective equipment including rubber boots, gloves, overalls and face masks.

- Use prepared and secure sites to take oily waste including contaminated clothing, gloves and masks that cannot be cleaned.

- Make use of washing facilities as available using normal household detergent.

- Do not eat fish from areas contaminated with oil. Do not fish in contaminated areas.

What not to do in case of an oil spill

- Without protective equipment do not try to remove oily waste

- Do not attempt to set the oil alight

- Do not run on oil covered areas.

- Do not go near any oil fires

- Do not use personal protective equipment for other purposes and only for cleaning efforts with authorities

- Do not take part in informal removal efforts – it is important to have proper planning, guidance, and supervision.

- Do not go barefoot on the beach

The rusting hulk of the Safer and its toxic cargo is a reminder of the threats posed by oil and the corporations that earn billion-dollar profits at the expense of people and the environment. From extraction to its end use, oil destroys livelihoods and environments either due to spills or because of climate change caused by oil and other fossil fuels. Nothing less than ending the oil age is needed to protect, not just the Red Sea, but the entire planet.

Ahmed El Droubi is senior campaigner at Greenpeace MENA