This year will remain in my memory for many more to come. My recollections of 2020 may only be compared to those of 2013.

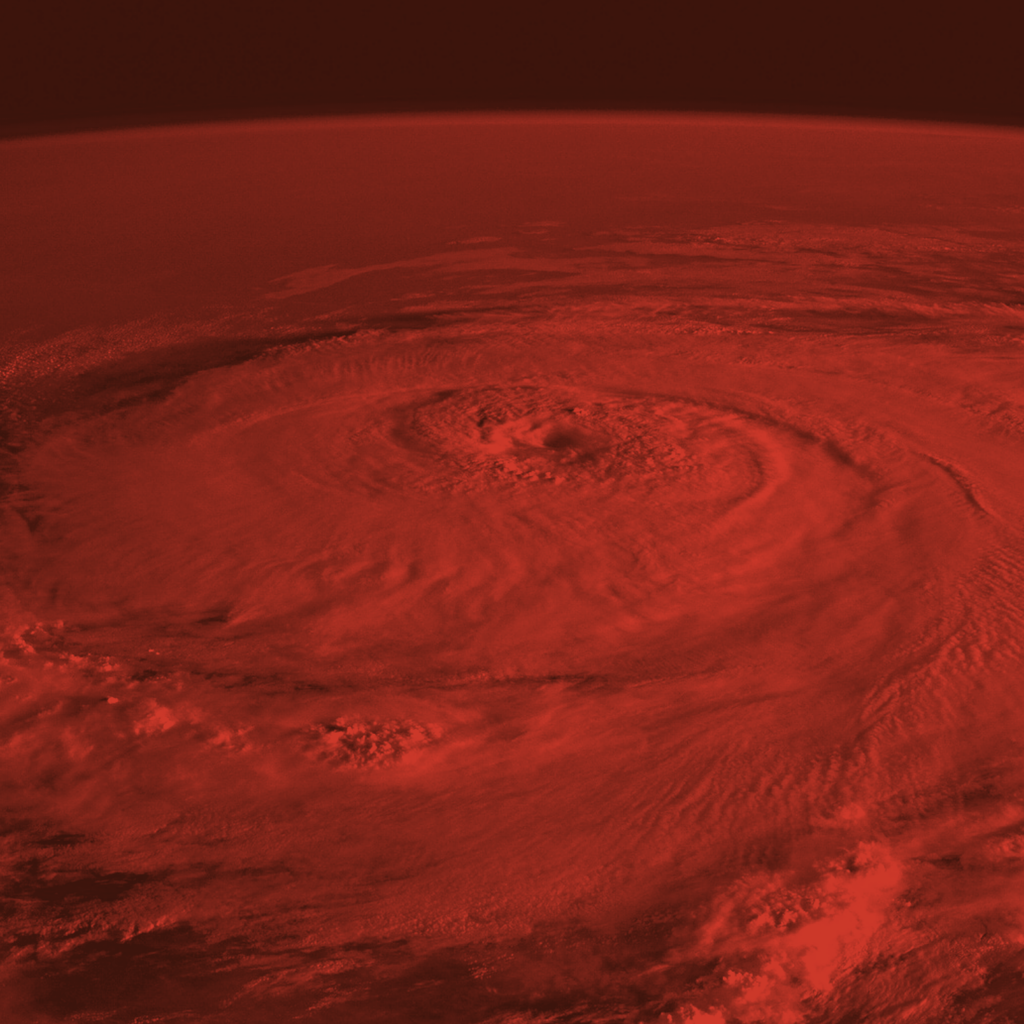

I was then the lead negotiator for the Philippine delegation to the United Nations Climate Summit in Warsaw around this time of the year. As my UN colleagues and I discussed the future of the climate, I received news from home. Bad news. Super Typhoon Haiyan had struck my family’s hometown of Tacloban as the strongest tropical cyclone on record to make landfall, which claimed thousands of lives and affected millions.

A week before the seventh anniversary of that catastrophic event, Super Typhoon Goni hit the country with such intensity, making it 2020’s strongest tropical cyclone at landfall and equaled if not surpassed Haiyan’s wind speeds when it made landfall in the island-province of Catanduanes. It swept across a region that is still recovering from the impacts of Typhoon Molave from a week before. That’s a sad record, a portent of things to come.

The Philippines is ground zero yet again. It’s not possible to fully describe in words the experience of a super typhoon: the sheer force of nature, the instinctive anxiety, the lingering grief.

It’s certainly not something that I would wish other people to understand from first hand experience. But even for those who live away from tropical areas, there are other extreme weather disasters that mark us in a deep way.

This year of the pandemic has also been the year of record wildfires in Australia, Brazil and the United States. Not two months ago, six million people in Burundi, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda suffered from historic floodings. Unfortunately, this is just a limited snapshot of the problems fueled by climate change, impacting people all over the world.

We are in a climate emergency. It’s unfolding now, just as the pandemic. And yet, many refuse to do something about it; particularly those most responsible for the carbon pollution behind the problem: fossil fuel companies and their backers.

A few days ago, Shell got roasted on Twitter for asking people what they would change to help reduce carbon emissions. Just the sheer audacity of a carbon polluter to put the burden on individuals to solve the climate crisis– which they have largely caused and profited from– is what drives millions of people to now hold them accountable. And we must. Their carbon emissions (historical and cumulative) have changed our climate for the worse, impacting our own ability to survive. This is particularly true for those who are in the most vulnerable situations before, during and after an extreme weather disaster.

And here I go back to the lessons from 2013. A new movement has emerged and the battleground has moved from the labs, the boardrooms and conference halls, to the streets, the classrooms, and courtrooms. This is the result of grassroots organising. The youth are striking for the climate, investors are pulling their money away from polluting businesses, and ordinary people are suing governments and corporations to protect their fundamental rights in the face of climate change.

Back in the Philippines, a broad coalition of local groups, workers, and fisherfolk came together with women, LGBTQIA+ activists, and concerned citizens to ask the Philippine Commission on Human Rights to conduct an inquiry into the responsibility of major companies like Shell, BHP Billiton, BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ENI, ExxonMobil, Glencore, OMV, Repsol, Sasol, Suncor, Total, RWE and other big carbon polluters for human rights harms resulting from the climate crisis. After a 5-year investigation, we now await the Commission’s findings. We expect it to be a landmark victory for the Filipino people and the global climate justice movement. We hope that the Commission will not fall short in finding responsibility against these big carbon polluters and issue recommendations that will inspire systemic change and put a halt to fossil fuel dependency.

As of writing, Typhoon Atsani is now making its presence felt in Northern Philippines. And another tropical disturbance is brewing over in the Pacific and is expected to hit the country in the next few days (either headed for the Bicol region which is still reeling from Typhoon Goni, or Eastern Visayas which was pummeled by Super Typhoon Haiyan).

It is only right that we continue to put public pressure on these big carbon polluters and raise our voices for justice. Let’s make 2020 count, let it be the year when we stand with climate-impacted communities as they reclaim their rights to a safe and stable climate. The climate emergency gives us massive reasons that make us lose sleep at night. But it also gives us all the good reasons to get out of bed in the morning. While we bring our voices to the boardrooms, courtrooms, and plenary halls of power, we hold firmly in our hearts that this battle will not merely be won or lost in the chambers of policy making, commerce, or law. This fight for climate justice will be won or lost in the chambers of people’s hearts.

Yeb Sano is the Executive Director of Greenpeace Southeast Asia

Tell President Duterte to acknowledge the urgent situation we are facing by declaring a climate emergency.

Discussion

Green &Peace needs true Green economy Now!

SURELY LET US WORK FOR CLIMATE JUSTICE FOR THE EARTH...YOU DESTROYERS OF MOTHER EARTH, WAKE UP AND ASK FORGIVENESS FROM GOD AND MAKE URGENT RESTITUTION .ASAP..FOSSIL FUELS CORP.,, MINING CORP. BIG BUSINESS LAND CONVERSION, ILLEGAL FISHING, AND MANY OTHERS AND WE WHO ARE COLLABORATORS OF THESE GROUPS BY OUR INVESTMENTS..AND OUR WASTEFUL THROW AWAY HABITS ESP PLASTICS...ETC,ETC..PLEASE GOD WE WILL LISTEN TO THE DYING CRY OF MOTHER EARTH AND ITS INHABITANTS..

Let us just hope and pray that our countrymen especially authorities will be awakened by the devastation left by typhoon Rolly. The blame on the worsening impacts of climate change need not only be on oil companies but most importantly on humans for if they can only be satisfied with a little of everything or be a minimalist the damages typhoons could not have been these worse. These oil companies will not extract so much fossil fuels down under if mankind don’t demand for a superfluous quantity of yhe different goods and services that they desire. Explanations are in my books and pamphlets.