“The goal of life is living in agreement with nature.”

— Zeno ~ 450 BC (from Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers)

Awareness of our delicate relationship with our habitat likely arose among early hunter-gatherers when they saw how fire and hunting tools impacted their environment. Anthropologists have found evidence of human-induced animal and plant extinctions from 50,000 BCE, when only about 200,000 Homo sapiens roamed the Earth. We can only speculate about how these early humans reacted, but migrating to new habitats appears to be a common response.

Ecological awareness first appears in the human record at least 5,000 years ago. Vedic sages praised the wild forests in their hymns, Taoists urged that human life should reflect nature’s patterns and the Buddha taught compassion for all sentient beings.

In the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, we see apprehension about forest destruction and drying marshes. When Gilgamesh cuts down sacred trees, the deities curse Sumer with drought, and Ishtar (mother of the Earth goddess) sends the Bull of Heaven to punish Gilgamesh.

In ancient Greek mythology, when the hunter Orion vows to kill all the animals, Gaia objects and creates a great scorpion to kill Orion. When the scorpion fails, Artemis, goddess of the forests and mistress of animals, shoots Orion with an arrow.

In North America, Pawnee Eagle Chief, Letakots-Lesa, told anthropologist Natalie Curtis that “Tirawa, the one Above, did not speak directly to humans… he showed himself through the beasts, and from them and from the stars, the sun, and the moon should humans learn.”

Some of the earliest human stories contain lessons about the sacredness of wilderness, the importance of restraining our power, and our obligation to care for the natural world.

Early environmental response

Five thousand years ago, the Indus civilisation of Mohenjo Daro (an ancient city in modern-day Pakistan), were already recognising the effects of pollution on human health and practiced waste management and sanitation. In Greece, as deforestation led to soil erosion, the philosopher Plato lamented, “All the richer and softer parts have fallen away, and the mere skeleton of the land remains.” Communities in China, India, and Peru understood the impact of soil erosion and prevented it by creating terraces, crop rotation, and nutrient recycling.

The Greek physicians Hippocrates and Galen began to observe environmental health problems such as acid contamination in copper miners. Hippocrates’ book, De aëre, aquis et locis (Air, Waters, and Places), is the earliest surviving European work on human ecology.

Advancing agriculture boosted human populations but also caused soil erosion and attracted insect infestations that led to severe famines between 200 and 1200 CE.

In 1306, the English king Edward I limited coal burning in London due to smog. In the 17th century, the naturalist and gardener John Evelyn wrote that London resembled “the suburbs of Hell.” These events inspired the first ‘renewable’ energy boom in Europe, as governments started to subsidise water and wind power.

In the 16th century, the Dutch artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder painted scenes of raw sewage and other pollution emptying into rivers, and Dutch lawyer Hugo Grotius wrote The Free Sea, claiming that pollution and war violate natural law.

Environmental rights

Perhaps the first real environmental activists were the Bishnoi Hindus of Khejarli, who were slaughtered by the Maharaja of Jodhpur in 1720 for attempting to protect the forest that he felled to build himself a palace.

The 18th century witnessed the dawn of modern environmental rights. After a yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin petitioned to manage waste and to remove tanneries for clean air as a public “right” (albeit, on land stolen from Indigenous nations). Later, American artist George Catlin proposed that Indigenous land be protected as a “natural right”.

At the same time in Britain, Jeremy Benthu, wrote An Introduction to Principles of Morals and Legislation which argued for animal rights. Thomas Malthus wrote his famous essay warning that human overpopulation would lead to ecological destruction. Knowledge of global warming began 200 years ago, when Jean Baptiste Fourier calculated that the Earth’s atmosphere trapped heat like a greenhouse.

Then, in 1835, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote Nature, encouraging us to appreciate the natural world for its own sake and proposing a limit on human expansion into the wilderness. American Botanist William Bartram and ornithologist James Audubon dedicated themselves to the conservation of wildlife. Henry David Thoreau wrote his seminal ecological treatise, Walden, which has since inspired generations of environmentalists.

A few decades later, George Perkins Marsh wrote Man and Nature, denouncing humanity’s indiscriminate “warfare” upon wilderness, warning of climate change, and insisting that “The world cannot afford to wait” – a plea we still hear today.

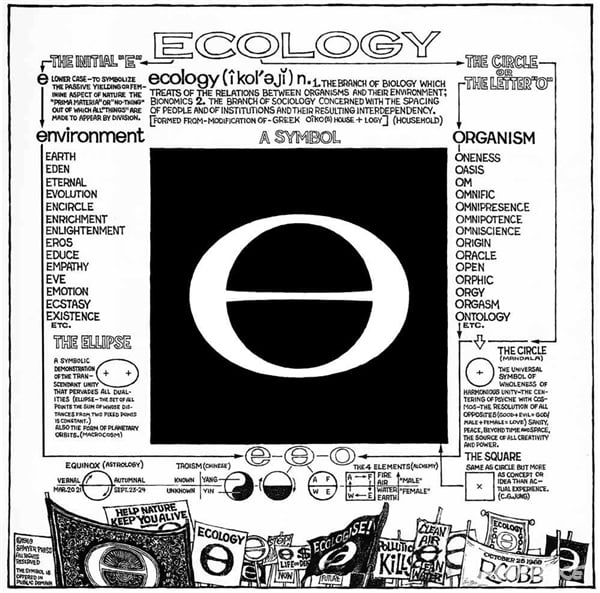

At the end of the 19th century, in Jena, Germany, zoologist Ernst Haeckel wrote Generelle Morphologie der Organismen in which he discussed the relationships among species and coined the word ‘ökologie’ (from the Greek oikos, meaning home), the science we now know as ecology.

In 1892, John Muir founded the Sierra Club in the US to protect the country’s wilderness. Seventy years later, a chapter of the Sierra Club in western Canada broke away to become more active. This was the beginning of Greenpeace.

Environmental action

“That land is a community is the basic concept of ecology,” wrote Aldo Leopold in A Sand County Almanac, “but that land is to be loved and respected is an extension of ethics … a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

In the early 20th century, the chemist Alice Hamilton led a campaign against lead poisoning from leaded gasoline, accusing General Motors of willful murder. The corporation attacked Hamilton, and it took governments 50 years to ban leaded gasoline. Meanwhile, industrial smog choked major world cities. In 1952, 4,000 people died in London’s infamous killer fog, and four years later the British Parliament passed the first Clean Air Act.

Ecology grew into a full-fledged, global movement with the development of nuclear weapons. Albert Einstein, who felt morally troubled by his contribution to the nuclear bomb, drafted an anti-nuclear manifesto in 1955 with British philosopher Bertrand Russell, signed by ten Nobel Prize winners. The letter inspired the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, in the UK – a model for modern, non-violent civil disobedience. In 1958, the Quaker Committee for Non-Violent Action launched two boats – the Golden Rule and Phoenix – into US nuclear test sites, a direct inspiration for Greenpeace a decade later.

Rachel Carson brought the environmental movement into focus with the 1962 publication of Silent Spring, describing the impact of chemical pesticides on biodiversity. “For the first time in the history of the world,” she wrote, “every human being is now subjected to contact with dangerous chemicals.” Shortly before her death she expressed the emerging ecological ethic in a magazine essay: “It is a wholesome and necessary thing for us to turn again to the Earth and in the contemplation of her beauties to know the sense of wonder and humility.”

Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss cited Silent Spring as a key influence for his concept of ‘Deep Ecology’ – ecological awareness that goes beyond the logic of biological systems to a deep, personal experience of the self as an integrated part of nature.

In The Subversive Science, Paul Shepard described ecology as a “primordial axiom,” revealed in ancient cultures, which should guide all human social constructions. Ecology was “subversive” to Shepard because it supplanted human exceptionalism with interdependence.

In India, villagers in Gopeshwar, Uttarakhand, inspired by Gandhi and the 18th century Bishnoi Hindus, defended the forest against commercial logging by encircling and embracing trees. Their movement spread across northern India, known as Chipko (“to embrace”) – the original tree-huggers.

In 1968, the American writer Cliff Humphrey founded Ecology Action. One media stunt involved Humphrey gathering 60 people in Berkeley, California, to smash his 1958 Dodge Rambler into the street, declaring, “these things pollute the earth.” Prophetically, Humphrey told Greenpeace co-founder Bob Hunter, “This thing has just begun.”

A year later, inspired by the writings of Carson, Shepard, and Naess, and by the actions of Chipko and Ecology Action, a group of Canadian and American activists set out to merge peace with ecology, and Greenpeace was born.

Co-founder Ben Metcalfe commissioned 12 billboard signs around Vancouver that read:

Ecology

Look it up.

You’re involved.

It’s hard to imagine now, but in 1969, most people did have to look it up. Ecology was still not a household word, although it soon would be.

In 1977, after two anti-nuclear bomb campaigns and confrontations with Soviet whalers and Norwegian sealers, Greenpeace purchased a retired trawler in London and renamed it the Rainbow Warrior, after a indigenous legend from Canada. The Cree story (recounted in Warriors of the Rainbow, by William Willoya and Vinson Brown) tells of a time when the land, rivers, and air are poisoned, and a group of people from all nations of the world band together to save the Earth.

Nearly a half-century after the foundation of Greenpeace, the global ecology movement has reached every corner of the world, with thousands of groups springing up to defend the environment. Meanwhile, the challenges facing us grow ever more daunting. The next half-century will test whether or not humanity can respond to the challenge.

Rex Weyler is an author, journalist and co-founder of Greenpeace International.

Resources and Links:

Environmental History Timeline: Radford University

Ramachandra Guha: Environmentalism: A Global History, 2000

The European Society for Environmental History: ESEH.org

Environmental History, Oxford Journals

Donald Worster: Nature’s Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas, 1977

J. D. Hughes: Ecology in Ancient Civilizations (U. New Mexico Press, 1975): Oxford Academic

Society for Environmental Journalists: sej.org

Letakots-Lesa (Eagle Chief) and Natalie Curtis on Pawnee songs: Entersection

William Willoya and Vinson Brown: Warriors of the Rainbow

Alice Hamilton, MD: Exploring The Dangerous Trades, 1943

Aldo Leopold: Sand County Almanac, 1949

Rachel Carson: Silent Spring, 1962

Barry Commoner: The Closing Circle, 1971

Paul Shepard: The Tender Carnivore and the Sacred Game, 1973

Gregory Bateson: Mind and Nature, 1978

Roderick Nash: The Rights of Nature, 1989

Deep Ecology for the 21st Century: A good survey of ecology writers, Arne Naess, Chellis Glendinning, Gary Snyder, Paul Shepard, and others