Humanity has already breached four of the nine ecological boundaries outlined in 2009 by Johan Rockström: climate change, loss of biodiversity, land-system change, and nutrient cycles.

Polluted farm lands in China

Most of us are familiar with the threats of declining biodiversity, deforestation, and global heating. However, nutrient cycles remain less well understood by the general public and by environmentalists.

Nitrogen and phosphorus are the two primary biological nutrients that circulate through Earth’s ecosystems. Every living organism on Earth requires both elements to form proteins and vital organic compounds. Both are required for our genetic DNA. Cells require nitrogen and phosphorus to make proteins, enzymes, and other organic compounds essential for life.

We typically add nitrogen and phosphorus to our gardens and farms in animal manure and synthetic fertilizer. However, human activity has so thoroughly disrupted Earth’s natural nutrient cycles that we have degraded soils and created aquatic dead zones.

Human influences

The rapid decimation of large terrestrial mammals was the first step in humanity’s disruption of nutrient cycles. Early farming communities and entire civilizations – the Maya and Mesopotamians, for example – collapsed after depleting their soils. Farmers learned about manure, compost, biochar, and crop rotation to help stabilize soils, but the rapid growth of humanity eventually depleted soils throughout the world.

Soil and a trowel at a polyculture farm in Bulgaria

During the nineteenth century, European nations mined potassium nitrate (KNO3) and imported bird and bat guano from Pacific islands to enrich their exhausted soils. As reserves of these nitrogen sources depleted, scientists sought ways to convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia. In Germany, Fritz Haber succeeded and by 1913, BASF chemical company was producing 20 tonnes of ammonia per day.

Industrial fertilizer has allowed the modern growth of human population. However, as we so often learn in ecology, there exist unintended consequences.

The use of fertilizer introduces new sources of nitrogen and phosphorus to the ecosystem, and concentrates these nutrients within certain watersheds. Typically, we think of a “nutrient” as a good thing. Nutrients make things grow. However, ecology is never that simple.

By pulling nitrogen and phosphate out of the environment and concentrating these elements in our agricultural and residential septic run-off, we have overloaded certain watersheds. The annual loading is now about 8.5 million tonnes of phosphorus and 54 million tonnes of nitrogen per year. Typically, if the local plant community cannot take up the added nutrient load, the nutrients move through groundwater, ditches, and streams into lakes and oceans.

A eutrophic lake, covered in algae

Throughout the world, lakes and marine shorelines become “over-productive” (eutrophic) where a few plant or bacteria species feast on the nutrients and choke out other lifeforms. Eutrophication can create dead zones and putrid lakes. Fish and amphibians can die out, leaving festering swamps. Swamps, of course, are part of nature too, but human activity has vastly accelerated this process and altered critical habitats.

Algae blooms virtually killed Lake Erie, between Canada and the US, Lough Neagh in the UK, Lake Taihu in Jiangsu China, Green and Fern Ridge lakes in the northwest US. We’re seeing this repeated around the world: thousands of dead or swampy former lakes. When algae blooms die off, they deplete oxygen, killing other organisms. Anoxia in the Baltic Sea, for example, has been caused by excessive nutrients. Similar ocean anoxic events are linked to present and past mass extinctions of marine life.

The disruption of Earth’s nutrient cycles remains as urgent as global heating and biodiversity loss. To come up with solutions, we must first understand the natural nutrient cycles of a healthy ecosystem.

The Nitrogen Cycle

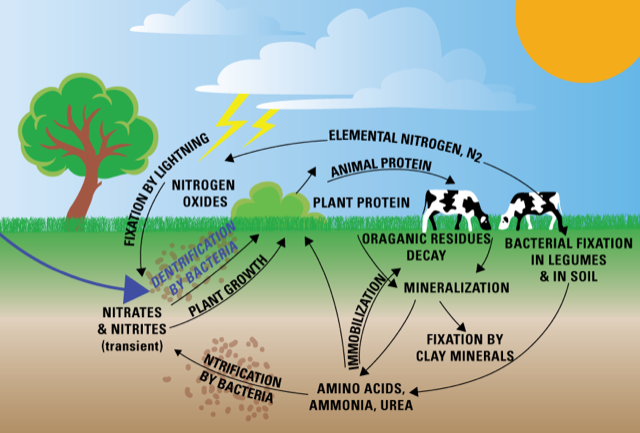

Visualisation of the Nitrogen cycle from the US Geological Survey

Nitrogen gas, N2, comprises about 78 % of our atmosphere, but is not readily available for organic use. Certain bacteria in Earth’s soils can capture nitrogen and convert it to ammonia, NH3, which they use for their own growth and reproduction, leaving some surplus for plants to absorb.

These nitrogen-fixing bacteria also live in the roots of certain plants, such a beans, peas, clover, and alfalfa. In a typical symbiosis, these plants provide the bacteria a home and carbohydrates. In return, the bacteria convert nitrogen to usable ammonia. Any extra ammonia remains in the soil for other plants.

This leads to the common practice of crop rotation in gardens and farms. After a particular food crop has depleted the soil of nitrogen, the grower may plant a legume crop to restore nitrogen. Farmers in the Indus, Yangtze, Huang Ho, and Mesopotamian river valleys had figured this out by 5,000 years ago, long before anyone understood organic chemistry.

Herbivores get their nitrogen by eating plants and play a significant role in distributing nutrients throughout the ecosystem. According to a study by Christopher Doughty and colleagues, in the past, marine mammals, seabirds, fish, and terrestrial animals, “likely formed an interlinked system, recycling nutrients from the ocean depths to the continental interiors,” moving nutrients from concentrated hotspots into biomes where other plants and animals could use them. However, the role of animals has been greatly diminished through biodiversity loss. Doughty estimates that due to anthropogenic extinctions and attrition, the capacity of fish, birds, and mammals to distribute nutrients has decreased by 94% across land and ocean.

Nitrogen concentration from fertilizers may help sequester a some carbon in terrestrial ecosystems, the one possible positive impact. However, a study by Peter Vitousek and others, “Human alteration of the global nitrogen cycle,” showed that human disruption of the nitrogen cycle has:

- Doubled the rate of nitrogen input into terrestrial ecosystems

- Increased the greenhouse gas N2O globally, contributing to photochemical smog

- Depleted calcium and potassium in soils, undermining long‐term soil fertility

- Contributed to acidification of soils, streams, and lakes

- Increased the eutrophication of lakes, rivers, estuaries, and coastal oceans

- Diminished biological diversity

- Reduced coastal marine fisheries

Taking action

As with virtually all ecological challenges, the scale of human enterprise remains a primary driver. Soils can naturally replenish nutrients after a modest harvest of crops, but not after an endlessly increasing harvest. Watershed ecosystems can process a certain increase in nutrient flow but not an endlessly increasing flow. On a national and regional level, we have to ask: what are nature’s limits?

Permaculture farm in Bulgaria

In local gardening, small farming, and in industrial farming, we need to avoid nitrogen and phosphorous fertilizers, and use all fertilizer and manure sparingly. Both gardeners and farmers must consider how much nutrient load their crops can actually absorb, and apply no more than this.

Farmers, gardeners, residents, and industry need to manage the uptake from their nutrient flow. This can be achieved with swales, dry wells, rainwater catchment, aerobic treatment, and bioremediation. All residential and industrial septic and sewage systems also need be maintained, cleaned, and inspected, to ensure optimum operation.

Ranchers, pet owners, and small farms have to manage manure run-off. Manure should be removed from fields, isolated from precipitation, and composted prior to use as a soil additive.

Clearing, paving, road building, logging, and construction all reduce natural plant uptake and increase nutrient flow into waterways. Road ditching and culverts should attempt to restore natural groundwater flow, not collect water in ditches.

Biological techniques use bacteria, fungi, and plants to remove or metabolize nutrients and pollutants. Bioremediation occurs naturally in healthy ecosystems and can be enhanced by design. Disturbed shorelines should be replanted with native species, especially those with high nutrient uptake, such as cattails (typha species). Certain useful mushroom species, such as Garden Giant (Stropharia rugosoannulata) can absorb nutrients and metabolize pollutants.

We can reverse the trend of increasing marine dead zones and eutrophic lakes. To achieve this, however, we must accept the evidence that nature’s bounty comes with limits.

Rex Weyler is an author, journalist and co-founder of Greenpeace International.

Resources and Links

“The Microbial Nitrogen-Cycling Network, ” Kuypers, MMM; Marchant, HK; Kartal, B (2011). Nature Reviews Microbiology.

“Nitrogen cycles: past, present, and future generations,” Galloway, J. N.; et al. (2004). Biogeochemistry. 70: 153–226. Springer.

Nitrogen cycle as Planetary Boundary: “A safe operating space for humanity,” Johan Rockström,et al. Nature, 461, p.472–475 (24 September 2009)

“Century-scale nitrogen and phosphorus controls of the carbon cycle,” Fred T. Mackenzie, Leah May Ver, Abraham Lerman; Chemical Geology, v. 190, 2002.

“An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle,” Nicolas Gruber & James N. Galloway

Nature, v. 451, 2008.

“The Nitrogen Cascade,” James N. Galloway, et al., BioScience, v. 53, No. 4, April 2003.

R. Carpenter, “Regime shifts in lake ecosystems,” Excellence in Ecology Series, v. 15, Ecology Institute, 2003); book review at Center for Limnology.

“Catastrophic regime shifts in ecosystems: linking theory to observation,” Marten Scheffer and Stephen R. Carpenter, Trends in Ecology and Evolution v.18 No.12, December 2003.

“Human Impact on Erodable Phosphorus and Eutrophication: A Global Perspective: Increasing accumulation of phosphorus in soil threatens rivers, lakes, and coastal oceans with eutrophication,”

Elena M. Bennett, Stephen R. Carpenter Nina F. Caraco; BioScience, v. 51, No. 3, March 2001.

“Evolution of phosphorus limitation in lakes,” D. W. Schindler, Science, v.195, January, 1977.

Robert W. Howarth, “Coastal nitrogen pollution,” Harmful Algae, 2008.

“Human alteration of the global nitrogen cycle: Sources and consequences,” P.M. Vitousek, et al. Issues in Ecology. August 1997.

“A Lake with A Thousand Faces,” Rex Weyler, May 2014: Salmonberry Arts.

“Hague & Gunflint Lakes Monitoring Report, Rex Weyler, 2017, Friends of Cortes Island.

“Biofilters: Guidance for using Bioswales, Vegetative Buffers, and Constructed Wetlands for reducing, minimizing, or eliminating pollutant discharges to surface waters,” Dennis Jurries, PE, State of Oregon, Department of Environmental Quality, January 2003.

“Bioremediation of Contaminated Soil,” Dana L. Donlan and J.W. Bauder, Montana State University

“Helping the Ecosystem through mushroom cultivation: mycoremediation,” Paul Stamets, Fungi Perfecti

Bioremediation, “Collaborating with Biohabitats,” John Todd, Ecological Design

“Global nutrient transport in a world of giants,” Christopher E. Doughty, et al., October 26, 2015, PNAS, US National Academy of Sciences.

“Ocean anoxic events,” I. Handoh, T. Lenton, Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 2003.