Today is the International Day of Awareness of Food Loss and Waste. Many of us instinctively feel guilty about throwing out food, especially when “690 million people in the world went hungry in 2019 – up by 10 million from 2018, an increase by nearly 60 million in five years,” according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). And, COVID-19 will likely make the situation worse, according to the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO).

And, it is some of the same systemic problems behind hunger that lead to food waste and its impact on the environment. The FAO estimates that if food waste were a country, it would be the 3rd largest greenhouse gas emitter in the world. There is much that we as individuals can do to tackle food waste at home, and each action matters. But the systemic problems behind the large volumes of food waste also need rectifying. To fix these problems we need to act together.

1. What is ‘food waste’?

Generally speaking, food waste describes food we throw away at home, as well as food lost at various points along the food chain, including on farms, in manufacturing, during transport, in storage and at retail centres. Experts who look at the overall issue from the field to our plates use the term ‘food loss and waste’ (FLW for short). While exact data about food loss and waste is hard to obtain, an increasing number of studies are shedding light on the problem.

2. Each year, how much food is wasted in the world?

The FAO has estimated that at least 30% of the food produced globally – worth around $940 billion USD – is wasted annually. The situation is worse in wealthier countries like in North America where food waste has been calculated to cost $278 billion USD each year and could feed 260 million people!

3. Who is responsible for food waste?

Large agribusiness and food and beverage (F&B) companies who control and shape the industrial food system play a major role in the scale of food loss and waste. Both global retailers and agribusiness conglomerates exercise enormous influence over the supply chain, forcing farmers – many in low-income nations – to shoulder the global burden of food loss and waste in international supply chains. In high-income nations, large companies using the industrial farming model disproportionately benefit from public financial support and tax breaks.

Big agribusiness and F&B companies further contribute to systemic food losses at the farm level because food commodity prices are kept too low. Their drive to lower the cost of raw commodities has the perverse effect of making food loss and waste a common side effect of our broken industrial food system. Sometimes, entire fields of crops go to waste if they are not cost-effective to harvest and transport. Growers also sometimes plant more crops than market demand to hedge against weather and pests, further lowering prices in bumper crop years and increasing waste in-field because it’s not lucrative to harvest.

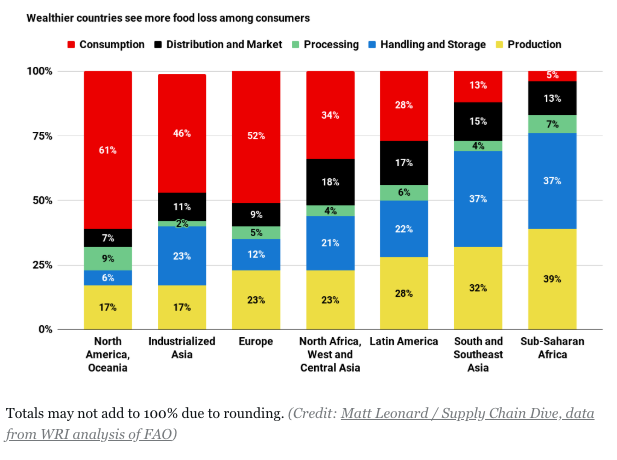

Despite lacking detailed data, most studies acknowledge that food loss and waste tends to take place more at the consumer level in richer countries and more up-stream at the production level in poorer countries. For example, lack of adequate farm storage for harvested products in poorer countries is one of the causes of food loss.

For wealthier countries, marketing by big food companies encourages consumers to over-purchase bulk food items, which then tend to generate food waste at home. Such phenomenon is the result of how food is marketed and sold by retailers. Let’s remember that food loss and waste is one of the symptoms of a sick food system, not the root problem.

4. How has COVID-19 impacted food waste?

The Covid-19 pandemic has compounded some of the previously existing systemic fragility, inequalities and failures of the industrial food system. Overall, food waste and loss most likely has increased during COVID-19.

Some farmers and farm workers simply had restricted access to farm fields due to various lockdown measures. Some have faced harsh working conditions that were inadequate to prevent COVID-19 transmission in food manufacturing plants.

Labour shortages have meant that there may not be enough farm workers at harvest time. For example, farmers in Canada reportedly had difficulties recruiting farm workers to harvest their products on time, unfortunately leaving crops rotting in the fields and generating food losses.

The economic impacts of the COVID-19 have also reportedly left many people and communities in a fragile state with increased poverty, reduced income, and, in some cases, more food insecurity than before. In these difficult moments, food waste and losses generated by the industrial food system are even more egregious and unacceptable.

5. Why should food waste matter to us and the environment?

The wasting of over 30% of the food produced globally each year shows that there is enough food in the world to feed everyone, but it does not always get to those who need it. Instead, it is wasted. Such waste translates into more deforestation, more irrigation and therefore greater use of water, more pressure on soil, more air pollution from fertilizers and pesticides, and higher greenhouse gas emissions.

Food loss and waste accounts for roughly 8% of global emissions, which is comparable to global emissions from road transport, and 4 times global emissions from aviation. Also, the industrial and global food system has lengthened the supply chain, resulting in more potential environmental damages due to waste and losses.

Food waste and loss is part of an industrialised food system model that continues to justify increased production to ‘feed people’ while dumping a third of the food in the trash. Food insecurity is in fact due to inequality, not lack of production. Therefore, the true solution is to change the food system model, which will minimise food loss and waste. Instead of an industrialised commodity trade model, we must start to relocalise production and consumption of ecologically produced food.

6. What can we do individually and collectively to reduce food loss and waste?

Individually, we can do our part to reduce food loss and waste by paying more attention to how we treat the food we eat. Some actions we can take are planning our meals before grocery shopping, buying no more than what we need, and being creative with our food leftovers. We need to avoid being seduced by bulk offers which might end up as waste. Another tip is to buy fresh seasonal produce directly from local farmers such as at farmer’s markets or Community Supported Agriculture and avoid extraneous steps along the supply chain where food can be wasted.

The business model drive to continually produce ‘cheaper’ food has established a dangerous mindset that our food isn’t really valuable, so it is unsurprising that food loss and waste is a central byproduct of their business model. Instead, we need to appreciate our food, the natural environment in which it grows, and all of the work that goes into growing and preparing it. Instead of a ‘cheap food’ business plan we need to convince our governments to adopt a fair price food system for farmers and farm workers while respecting our planet to continue to produce healthy and nutritious food.

7. How can a just and green recovery reduce food waste?

A just and green recovery can help to reduce food loss and waste through policy adoption and community investments. For example:

- Shorten supply chains to relocalise food systems by encouraging and expanding direct-to-consumer systems like farmers markets.

- Support cities and municipalities to enable residents to reconnect with food through community projects such as allotment gardens, garden rooftops, collective community kitchens, and zero food waste programs.

- Provide better harvesting and storage facilities at farm and rural level to minimise food losses.

- Support the adoption of ecological farming practices that protect crops without harming the environment and the health of farmers and farm workers.

- Ensure a fair pricing system for farmers.

Let’s not waste our opportunity!

In 2021, the United Nations will organise a Food System Summit. It could be an opportunity at global, national, and local levels to put the issue of food loss and waste on the public agenda. We can change our current failing food system into a green and just one that is not only more respectful of ecological boundaries, but also ensure food justice for all. The corporate business as usual approach must be exposed, challenged, and replaced with food sovereignty to ensure the needs of producers, consumers, and nature are at the heart of our food system. Let’s not waste such an opportunity!

Tell us what you are doing to reduce food waste in your daily lives. What are some local groups and organisations doing to create a better and just food system? Share your good news to inspire us all.

Éric Darier & Monique Mikhail are Senior Strategists at Greenpeace International based in Montreal and San Francisco respectively.