Ten years ago on 12 December 2015 in Paris at the UN climate conference COP21, a momentous agreement was reached, committing governments to efforts aimed at limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

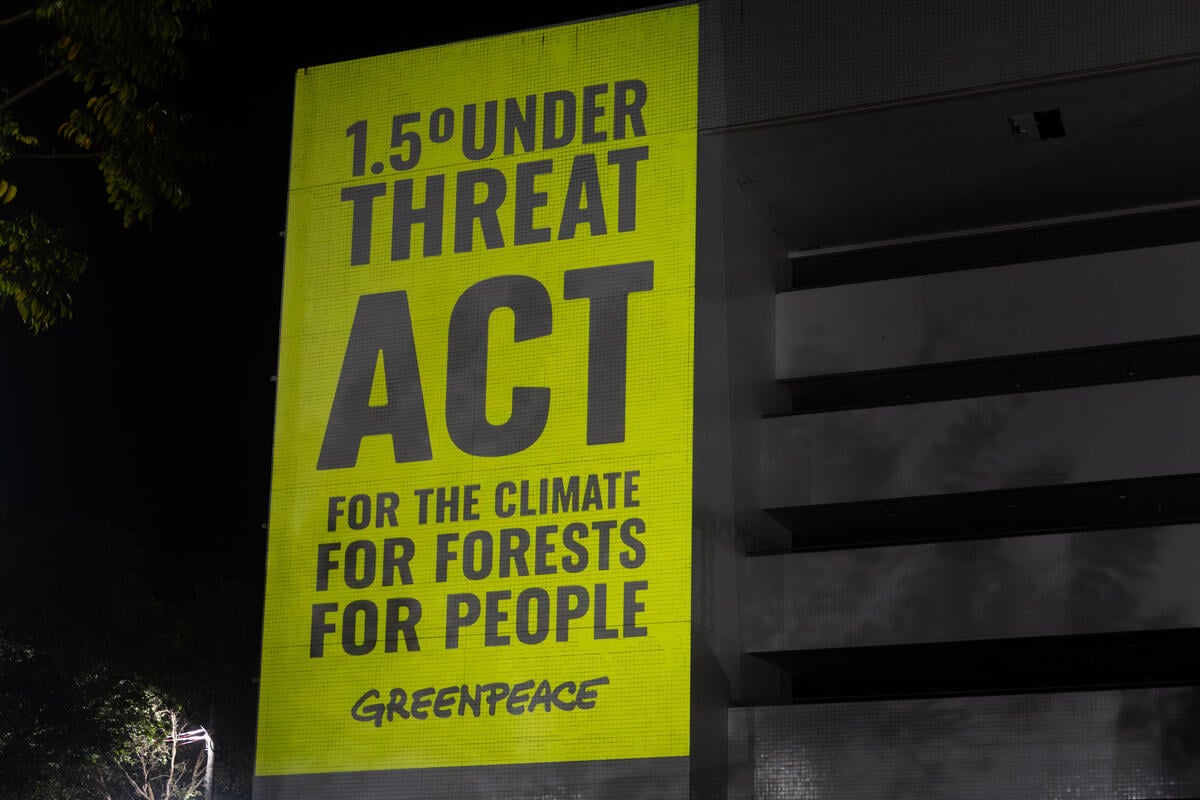

But 10 years later, the world is still dangerously off track from meeting the 1.5°C limit and much faster action to reduce fossil fuels emissions and end deforestation is needed. So what has the Paris Agreement achieved, what happens next and what is needed to limit climate change?

The global temperature trajectory is falling

The Paris Agreement gave the world a new direction and accelerated the clean energy transition, proving itself pivotal in lowering projected global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This landmark accord has helped shape government policies and instigated multiple net-zero pledges from states and non-state (business) actors.

The projected temperature increase has since fallen from just below 4°C at the time of adoption of the Paris Agreement to just below 3°C. There is still a large 1.5°C ambition gap, however, with current warming projections still well above the Paris Agreement’s goal.

Consequently, the UN has warned in its latest Emissions Gap Report of a looming temporary exceedance – or overshoot in technical terms – of the 1.5°C limit, very likely within the next decade. This must become a rallying call for action, ensuring we limit this overshoot through faster and bigger reductions in GHG emissions to minimise future climate risks.

Ambitious energy futures have become the mainstream

Ahead of COP21 back in 2015, Greenpeace published the final version of its Energy [R]evolution scenario, showing that a highly efficient and 100% renewable energy system was not only possible, but absolutely necessary to prevent catastrophic warming.

Our report was at that time considered a radical vision of possibility. That vision, however, is now becoming reality on the renewables front. Solar and wind power are now the most cost-effective forms of electricity generation, outperforming all other technologies in both cost and speed of installation.

Since 2021, the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook (WEO) has also included a ‘Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario’ and in its 2025 WEO, the IEA said it still sees fossil-fuel use peaking before or around 2030, despite a recent surge in political support for coal, oil and gas.

That same report affirmed that a renewable energy transition is underway and could solve the climate crisis along with other societal needs. Solar, wind and energy smart solutions are now clearly ready to deliver faster CO2 cuts than what countries currently assume in their pledged climate targets.

Since 2010, the cost of solar, wind and batteries has respectively fallen by 90 percent, 70 percent and 90 percent, the IEA figures show, with further declines of 10-40 percent expected by 2035.

The key now is for governments to speed up the transition by pushing fossil fuels out of the way and eliminating barriers related to grids, storage and climate finance gaps. But this must also be done as part of a just transition to ensure a fast, orderly and fair fossil fuel phase-out.

Climate action plans are still insufficient

During the UN climate conference COP30 in Belém, Brazil, in November, the UN published an aggregate analysis of countries’ 2035 climate action plans – known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – and exposed again, however, an alarming lack of ambition.

Under the Paris Agreement, countries are required to submit new, successively ambitious NDCs every five years to the UNFCCC secretariat. The updated 2025 Synthesis Report, however, showed that new 2035 NDCs will only produce a projected 12 percent cut in global emissions by 2035. This is woefully short of the 60 percent global reduction needed (compared to 2019 levels).

The main culprits are the G20 countries, collectively responsible for 80 percent of global emissions. A Greenpeace report, the 2035 Climate Ambition Gap, found that G20 climate action plans would yield a paltry 23-29 percent cut in emissions towards the 60 percent global target.

G20 countries are home to the world’s largest producers and consumers of fossil fuels, yet none of their 2035 NDCs include credible plans to phase them out. Their actions in the coming years will make or break the 1.5°C goal and it’s critical they ramp up ambition now. Above all, developed countries should be leading the way.

Paris Agreement a shining, resilient light of global climate politics

The significance of the Paris Agreement cannot be overestimated. It was the first binding agreement that committed all nations together to combat climate change and adapt to its effects. It was adopted by 195 parties and entered into force on 4 November 2016.

Despite efforts to undermine the accord by the US administration under President Trump – who has twice initiated a US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement – the Paris Agreement has withstood multiple challenges and been repeatedly affirmed by successive COPs.

No other country has exited the Paris Agreement and at COP28 in Dubai, at the first Global Stocktake (GST) of action since the Paris Agreement, governments agreed for the first time to transition away from fossil fuels in a just, orderly and equitable manner and, secondly, to end deforestation by 2030.

These GST decisions are like the bedrock of the Paris Agreement – clearly spelling out the foundational requirements to keep the 1.5°C limit in sight.

A landmark advisory opinion in July from the International Court of Justice, also put countries on notice that they are legally obliged to protect the world from further warming, confirming that the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit is the legal binding temperature threshold.

Despite these achievements, is the Paris Agreement doing enough? The answer is still no.

Among many pressing demands, more money for climate action, adaptation and loss and damage is urgently needed and Greenpeece is calling for countries to start making oil and gas companies pay for climate damages through a Polluters Pay Pact and campaigning for an end to deforestation.

Greenpeace France activists also marked the Paris Agreement anniversary with a protest denouncing, among others, French President Macron and US President Trump for “10 years of climate sabotage”.

It’s time that political and business leaders around the world finally stand with the millions of people demanding climate and biodiversity action.

At COP30, roadmaps to end fossil fuels and deforestation were on the agenda

So, 10 years after the Paris Agreement, all eyes were on COP30 in Belém, where it was hoped that historic progress to phase out fossil fuels and end forest destruction would be achieved.

The reality proved otherwise, where geopolitical divisions saw a call by the Brazil presidency for the adoption of roadmaps to end our dependence on fossil fuels and to end deforestation were slashed from the formal COP30 outcome.

This result again showcased the disconnection between COPs and people calling for action.

On the positive side though, more than 80 countries from the EU to Latin America and the Pacific were supportive of a roadmap to transition away from fossil fuels and more than 90 countries were ready to back a deforestation roadmap. And Brazil committed to a Presidency-led initiative to take forward the roadmaps in 2026, reporting to COP31.

The fossil fuel roadmap might have been blocked this time, but nothing can erase the fact that a roadmap is now the expectation from a large and growing group of countries, not a radical idea. That demand isn’t going away and it has now created a clear benchmark for future action.

Moving forward from COP30, we must maintain momentum for both of these roadmaps and reinforce initiatives from these ‘coalitions of the willing’ to drive actionable results at the next COPs and to ultimately achieve the 1.5°C limit anchored in the Paris Agreement.

Together we can resist, rise and renew!