Cleanspark’s Bitcoin boom in rural Georgia, backed by Wall Street giants, raises environmental and social concerns challenging the promised benefits to rural communities.

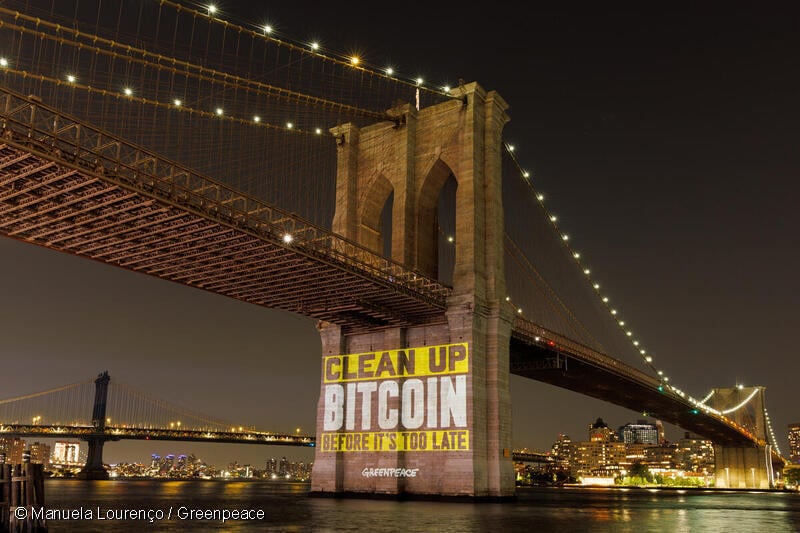

Introduction

CleanSpark is one of the many Bitcoin mining companies expanding operations in Georgia and across the American South, attracted by lax regulations, tax subsidies, and low energy costs. Beyond the large carbon emissions, growth of the industry means residents of often-rural towns and small cities are confronting the disruptive and polluting impacts of Bitcoin mines in their backyards. Sandersville, Georgia is one of those rural communities where CleanSpark is developing what will be the company’s largest facility.

Growth of Bitcoin mining in places like Sandersville is supported by investments from big Wall Street firms. Financial giants BlackRock and Vanguard are CleanSpark’s largest shareholders and have provided the company with capital used to maintain and expand its facilities across Georgia. Yet, financial companies haven’t acknowledged how their investments in Bitcoin mining companies are fueling the carbon-intensive and polluting facilities that are popping up in rural areas across the country.

Georgia’s Bitcoin Boom

Georgia is becoming a popular location for Bitcoin mines. Data from The Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance found that Georgia was the most productive Bitcoin mining state in 2021, housing around 31% of all U.S. Bitcoin production. That’s a significant amount since the U.S. hosts more Bitcoin mining than any other country. Miners are coming to Georgia in part for the low cost of electricity where the average energy price of 10.3 cents/kWh is lower than the U.S. average of 12.09 cents. CleanSpark is one of the companies driving the growth of Bitcoin mining in Georgia and operates facilities all across the state including in Norcross, Washington, College Park, two newly-acquired facilities in Dalton, and the company’s largest in Sandersville.

Sandersville is a small city in central Georgia with a population of under 6,000 residents that used to be called the “Kaolin Capital of the World” due to its extensive production of kaolin, a clay used in making porcelain. The town recently shifted to a new “mining” industry: Bitcoin. Mawson Infrastructure built the town’s first Bitcoin mine in 2021. The site grew from an acre of shipping containers filled with specialized Bitcoin mining computers called ASICS to 41 containers—12 of which use as much electricity as the entire town of Sandersville. In October 2022, CleanSpark bought the site and equipment from Mawson, marking the company’s fourth location in Georgia. CleanSpark now operates the facility with thousands of ASICS that use as much electricity as the nearest 49,000 households racing to solve algorithms in order to win newly minted Bitcoin and fees in return for validating Bitcoin transactions. The site is operating at a reported capacity of 80 MW with plans to expand to 230 MW by the end of 2023, dwarfing the 25 MW a day used by the city of Sandersville. In a September press release, CleanSpark said construction is underway for the 150 MW expansion and expected to be completed by the end of the year. Meanwhile, the Municipal Energy Authority of Georgia (MEAG) is building a 200MW substation and related infrastructure which will be used to power the additional capacity at the Sandersville site and expects the substation to be completed in 2023 and the power-line connections in early 2024.

Bitcoin Backed by Wall Street Giants

Buying facilities, equipment, and land all requires capital which CleanSpark has gotten in part from the financial services industry. CleanSpark is a publicly-traded company which means the company can raise capital through issuing stock to the public and large investors. CleanSpark became publicly listed in 2020 and in the last few years has used additional equity offerings – putting up more company stock for sale – to raise capital for funding expansion. CleanSpark bought the Sandersville facility in September 2022 for $33 million, an acquisition that came after raising $211.86 million through two equity offerings in 2021 and another $40 million deal in 2020. Issuing new shares requires help from an investment bank who provides underwriting – verifying the company’s finances, setting the sales price, and facilitating the deal. All of CleanSpark’s recent offerings were led by HC Wainwright, an investment bank based in New York, who has provided underwriting for many Bitcoin mining companies.

Big financial companies and institutional investors bought up many of CleanSpark’s shares. Currently, CleanSpark’s top two shareholders are BlackRock, with 4.45% of shares, and Vanguard, with 4.05% of shares – their combined holdings were valued at $67.91 million. [1] Both companies also increased their shareholdings as of the latest financial filings in August, 2023, BlackRock by 33% and Vanguard by 45%. [2] Other shareholders include big banks and asset managers like JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, and Fidelity.

CleanSpark’s Bitcoin Greenwashing of Climate Pollution

CleanSpark claims to take a more sustainable approach to Bitcoin mining and to support renewable energy generation despite evidence that the company’s facilities rely largely on fossil fuels. A press release issued at the time of purchasing the Sandersville site states, “CleanSpark draws power predominantly from low-carbon sources, such as nuclear energy, and boasts a clean energy profile that is over 90% non-carbon.” CleanSpark published its Energy Mix and Consumption Data in its 2022 ESG report and claims that from October 2021 to September 2022, the company’s energy mix across four locations was 94.02% “clean energy,” 5.70% “carbon-based,” and 0.28% “undisclosed.” [3]

Yet, other data and independent analysis contradict CleanSpark’s “sustainability” claims. Apart from the lack of specificity in what constitutes “clean energy” and vague sourcing of these figures as simply “data from the power providers,” there is a huge discrepancy between these numbers and Georgia Power’s energy mix, the electric utility that serves Sandersville and much of the state. Georgia Power, which generates most of the power it sells, had an energy mix in 2021 that was 47% gas and oil, 16% coal, 24% nuclear, and 8% renewables. Thus, the majority of its sources are fossil fuels. While the supply of renewables and fossil fuels vary in different parts of the state, that doesn’t account for the wide discrepancy with CleanSpark’s statements.

A joint investigation by the New York Times and tech non-profit WattTime further challenges CleanSpark’s claims about using clean energy. The investigation found that the Sandersville site used a daily average of 72 MW of electricity of which 91% came from fossil fuels, leading to 314,000 tons of CO2 emissions per year. The analysis also estimated that CleanSpark’s College Park, Georgia mine got 91% of the facilities’ power from fossil fuels—emitting 166,000 tons of CO2. These numbers are a far cry from CleanSpark’s “90% non-carbon” promise.

CleanSpark may claim to operate on “clean energy” based on purchasing renewable energy credits (RECs). The company acknowledged participating in the Georgia Simple Solar program that lets customers buy RECs to compensate for fossil fuel usage and carbon emissions. RECs represent one MWh of electricity from a renewable source that can be bought and sold, and lets an energy user claim credit for renewable energy produced elsewhere. However, researchers have found that companies buying RECs does little to spur renewable energy development and offset emissions. Experts argue that RECs are helping companies inflate their sustainability claims while doing little to drive energy transitions and address the climate crisis. RECs allow companies to claim they are meeting renewable energy targets while continuing to rely on dirty fossil fuel energy. Purchasing RECs is different from directly investing in renewable energy infrastructure, such as by owning solar panels or wind turbines, or signing Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) directly tied to renewable energy generation.

Bitcoin Noise Pollution in Georgia

In addition to the carbon emissions contributing to the climate crisis, Bitcoin mines are also very loud, often disturbing nearby residents. Due to the massive computing power used during the mining process, the computers generate substantial amounts of heat and must therefore be cooled to avoid damaging the equipment. Cooling systems often involve industrial-grade fans and air conditioning units that—when combined with the constant operation of mining rigs—result in persistent noise. The relentless hum of these machines can extend far beyond the confines of the mining facilities, unfortunately impacting surrounding neighborhoods.

Communities across the South have experienced this unexpected noisy intrusion into their daily lives, as residents from Arkansas to Tennessee report disruptions right outside their homes. For example, residents of Adel, Georgia have been plagued by nonstop noise from Bitcoin mines. The incessant drone of fans and machinery, often louder than the recommended cap of 70 decibels, goes beyond mere inconvenience: prolonged exposure to loud noise can have negative effects on people’s mental and physical well-being, interfering with sleep schedules, increasing stress levels, and contributing to long-term health issues like cardiovascular disease.

Many of CleanSpark’s facilities in Georgia operate with the same loud air-cooling processes. Thus, the Sandersville mine may bring disruptive noise to nearby residents, and students and faculty at the Oconee Fall Line Technical College, a local community college, that is less than half a mile away. CleanSpark’s Norcross mining site utilizes an immersion cooling system that cools computers through submersion in synthetic oil – a process that reduces the amount of energy used and decreases noise pollution by not relying on fans. Though a quieter and more efficient method, it has so far been limited to the smaller 20 MW site in Norcross.

As CleanSpark announces a planned expansion of the Sandersville site—a $145 million deal to double the fleet’s mining capacity for a “massive 150 MW expansion”—there could be more noise and disruption in store for residents.

Bitcoin Community Impacts and Unmet Promises

CleanSpark promises to help Sandersville through increased tax revenue and job creation, promises that are appealing in rural communities like Sandersville that relied on a single industry that’s gone bust. Sandersville is unique in having its own electrical grid and has agreed to sell electricity to CleanSpark which generates revenue for the city from the sales and taxes. Some elected city officials have been supportive of the mine and the potential for public revenue. But, the long term impacts remain unknown and there is little data on how the facility impacts local jobs, energy prices, and quality of life.

However, Bitcoin mining is not a perfect solution and for many towns and cities hasn’t ushered in an era of renewed prosperity. Mining facilities typically have relatively few long term employees, often hiring only a dozen workers per facility, and may be less labor intensive than other industries and energy-intensive facilities. [4] A National Bureau of Economic Research working paper finds that Bitcoin mining can lead to higher energy prices for nearby residents and small businesses which can outweigh increased tax revenue. In 2022, CleanSpark had only around 80 workers spread across all its facilities. Bitcoin mining is a boom and bust industry tied to the volatile price of Bitcoin – there was a wave of bankruptcies when Bitcoin’s price dropped in 2021. Miners can also easily relocate their facilities, leaving communities high and dry, and move to wherever they can find the cheapest energy.

The biggest beneficiaries of Bitcoin mines end up being the companies’ executives , owners and investors who don’t live in the community. Instead of broad economic development and prosperity, many towns with Bitcoin mines have been left with noisy and water-intensive facilities and little public input or oversight about the operations. In Kentucky, officials rejected a Bitcoin mining company’s request for energy price discounts because it would contribute to higher prices for regular ratepayers and strain the grid’s energy supply.

Other communities in Georgia and across the U.S. have become wary and are working to prevent expansion of the Bitcoin mining industry. The city of Forsyth, Georgia blocked a Bitcoin mine, partially due to the potential noise, by denying the company’s requested zoning change. Meanwhile in North Carolina, the Clay County Commission board passed an ordinance blocking commercial crypto mining in the county.

Endnotes

1 Data collected from Bloomberg Terminal and based on holdings and share prices as of August 31, 2023.

2 Data collected from Bloomberg Terminal.

3 This data does not include the Sandersville site, which was purchased after the evaluation period.

4 See National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, “When Cryptomining Comes to Town: High Electricity-use Spillovers to the Local Economy,” for analysis of the local economic impacts of crypto mining including on electricity prices and the labor market. However, there is a lack of data and reporting about job creation from crypto mining which makes it difficult to reliably assess the economic development impacts.