On February 28, 2026, Trump illegally went to war with Israel against Iran, seemingly without having thought through the likely consequences of his actions. The reckless and violent attack cut short negotiations with Iran and ever since, the administration has struggled to articulate consistent goals or strategic aims.

This latest war caps one year of bombings, invasions, sabre-rattling, and threats against U.S. allies from the self-styled “peace president.” Tragically, over a thousand lives have already been lost and the conflict appears to be growing. Trump and Netanyahu’s illegal military strikes have only inflicted more harm on the people of Iran, who have already endured a brutally violent crackdown in which thousands of protesters and bystanders have been killed, with many more still feared dead.

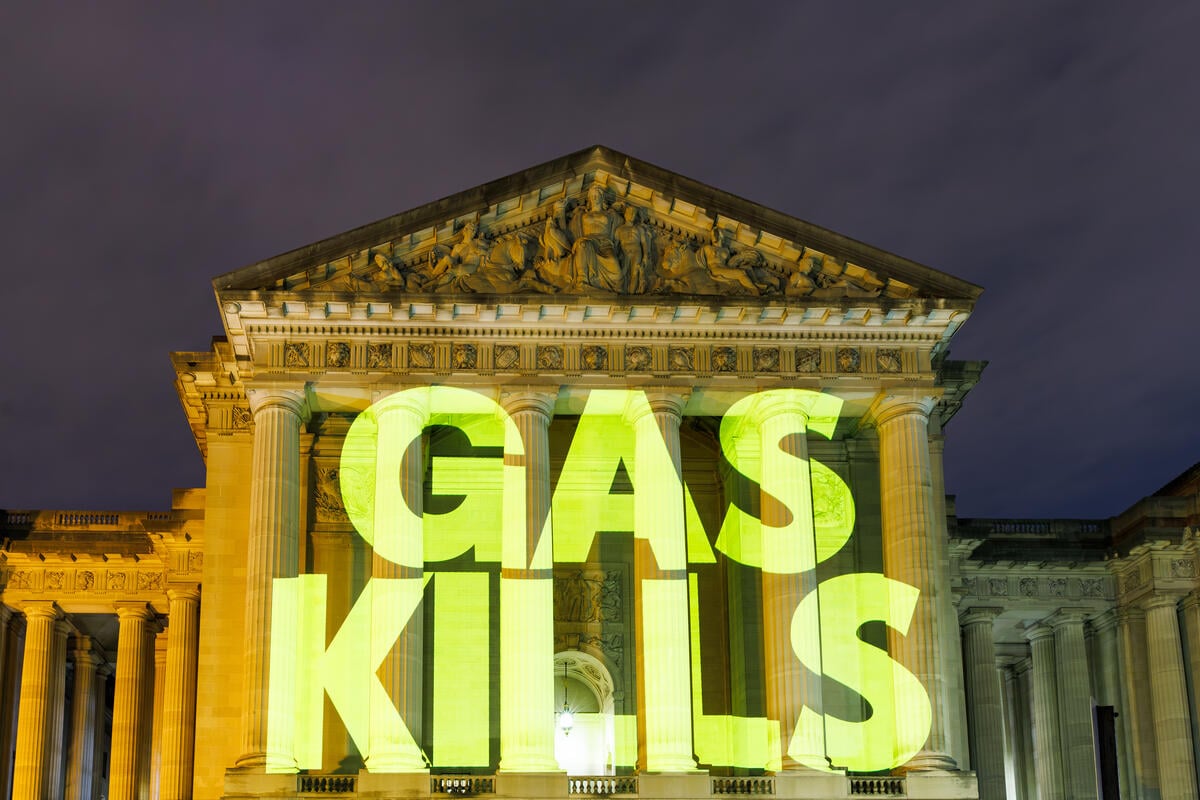

Trump’s stated desire to control resources – especially oil and gas – is behind most of this foreign policy violence. As the Iran attack has illustrated, fossil fuel dependence and waging war in a region responsible for more fossil fuel production than any other region in the world is inherently expensive and dangerous. Yet another war shows us why it is well past time to dump fossil fuels.

Fossils are global

The Strait of Hormuz, a strategic water passage through which 20% of the world’s oil must transit, has been almost completely blocked by conflict in the area. The Strait is particularly important for oil and liquified natural gas (LNG) shipments, and the stoppage of traffic has led to spikes in oil and gas prices globally. As of this writing, crude oil spiked to over $100 per barrel, and LNG benchmark prices have surged in Europe and Asia.

Apparent Iranian airstrikes on two state-owned LNG facilities in Qatar were another example of how war can directly and immediately change energy markets, access, and security globally. After the military strikes, natural gas prices jumped and state-owned QatarEnergy said it would halt LNG production as a result. Two days later, QatarEnergy declared force majeure, releasing it from its contracted business deals with energy buyers.

Qatar’s disruption to normal LNG trade flows both spiked prices and created immediate uncertainty for buyers about where to source LNG, especially for European countries. This will generate enormous windfall profits for some well-positioned oil and gas companies. One report suggests that traders and exporters of U.S. LNG will likely take in $870 million in additional weekly profits – rising to $20 billion per month if Qatari LNG supply isn’t resumed by the summer.

On March 8th, the Israeli Defense Force struck at least five energy sites, including fuel storage facilities used for the military, near Tehran. The strikes led to fires at fuel depots burning for hours, unbreathable toxic air, and black rain in an area home to 10 million civilians. In response, Iran has threatened retaliatory strikes on energy facilities in neighboring countries. A spokesperson for Iran’s Revolutionary Guards told The Guardian “If you can tolerate oil at more than $200 per barrel, continue this game.”

A very similar global dynamic played out in 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the energy market disruptions that followed. Research from Greenpeace USA, Oil Change International, and Global Witness found that U.S. oil and gas companies were positioned to earn tens of billions in windfall profits after the invasion, and that U.S. and European companies had contributed nearly $100 billion to Putin’s war chest since the 2014 invasion of Crimea.

A fossil-fueled world is never affordable

When oil and gas prices surge, everyday people feel the impact. Consumers face higher costs for heating, electricity, and gasoline, and inflation grows.

Our economy is tethered to volatile global energy markets when fossil fuels dominate.

Crude oil is a globally-traded commodity, which means that a supply crunch in one part of the world will usually raise gasoline and energy prices here in the U.S. The fact that the U.S. is the world’s largest oil and gas producer offers little to no protection to U.S. consumers. We may “drill, baby, drill” here at home, but the oil belongs to the oil companies, who will happily export it at a higher price. With the rise of global LNG markets, the same dynamic is increasingly true for gas as well.

On March 6th, six days after the U.S. and Israel began military strikes in Iran, gas prices at the pump were up an average $0.34 from the week before. By March 9th, they had risen to $3.48 per gallon and airfares may also rise as a result of the warfare. Even the price of many consumer goods can increase with fossil fuel price volatility: any product that is made from fossil fuels (think plastics or petrochemicals) and goods that are shipped or transported using fossil fueled vehicles are vulnerable.

Trump has said the war with Iran could last for weeks, but an end to the conflict is not immediately apparent and the situation remains hard to predict. Trump has yet to articulate a serious and consistent rationale for the military actions. On gas prices for people in the U.S., Trump says “if they rise, they rise”, discarding his previous campaign promises on lowering gas prices. That instability threatens to keep energy markets in chaos.

Many in the U.S. already disapprove of the war, and now U.S. companies are raking in millions, even billions in profits, while individuals and families pay the price. The profits from high energy prices strongly favor the rich, who own the largest stakes in energy companies.

The immediate price surges, energy security risks, inflation, and corporate exploitation of wartime illustrate just how insecure and unaffordable fossil fuels are. Phasing out fossil fuels is essential for long-term, consistent affordability and security of energy. Unlike globally traded oil and gas, renewables are not subject to the same geopolitical risks of fossil fuels. Notably, the affordability of renewable energy would likely be insulated from global geopolitics in ways that are nearly impossible with oil and gas.

War is paid for in human lives and shattered futures – and it poisons land and water, destroys ecosystems, and accelerates climate breakdown. There is no climate justice without peace, and no lasting peace without human rights.

The cycle of violence and profit must end. We call for peace, accountability, and for leaders to transition to a just world where security does not depend on fossil fuels and force.