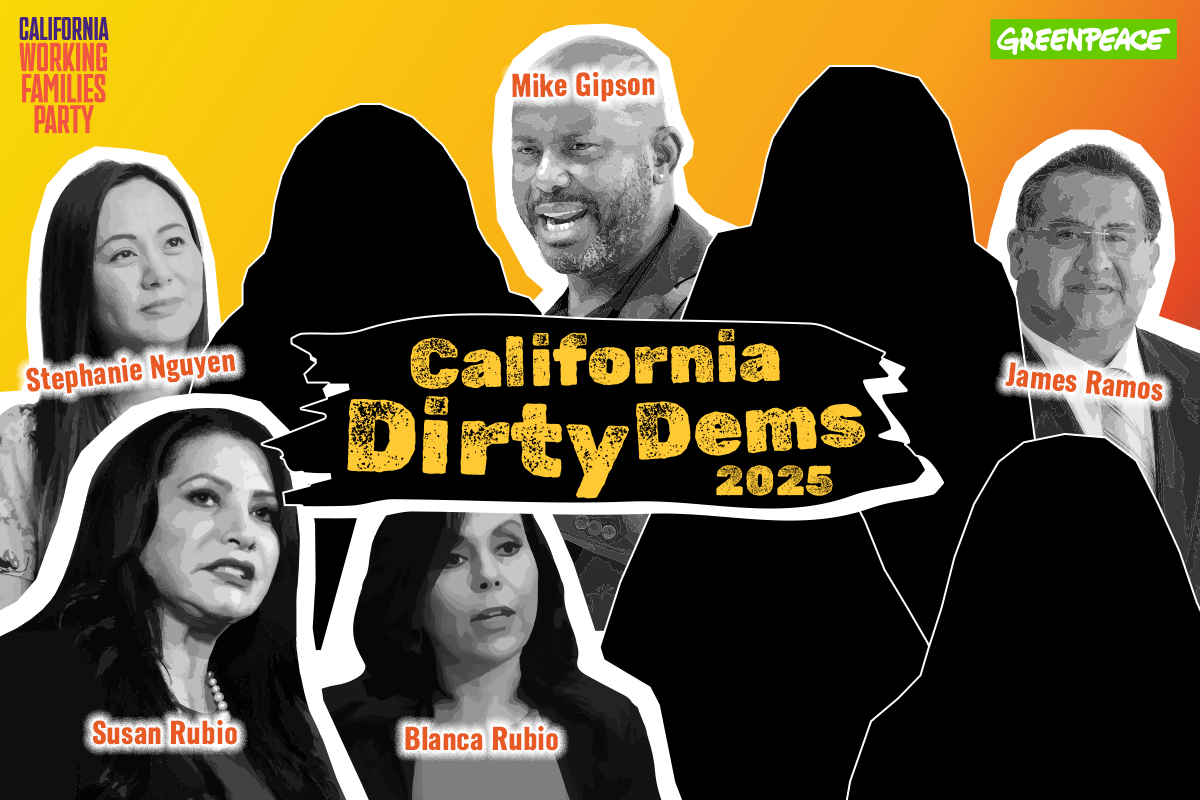

FRESNO, CA (May 6, 2025)—As part of the ongoing “Dirty Dems” campaign, Greenpeace USA, in collaboration with the California Working Families Party and Courage California, continues to hold California State legislators accountable for their damaging connections to the oil and gas industry and their failure to support critical climate, economic justice, and progressive priorities.

In its final week, the campaign turns to Fresno’s Assembly Member Esmeralda Soria. Though Soria has only spent just over two years in office, she has already directly accepted $53,000 from the oil and gas industry, including $29,500 in just the last session alone.

Amy Moas, Ph.D., Greenpeace USA Senior Climate Campaigner, said: “Assembly Member Soria’s ties to the fossil fuel industry are particularly alarming because she signed the No Fossil Fuel Money pledge while running for Congress in 2020. Her abrupt reversal to supporting toxic polluters begs the question: why is she unwilling to stand up for resilient families and a healthy future? In two short years, Soria has quickly made her priorities and true alliances known.”

Assembly Member Soria has earned failing grades from every major environmental and progressive scorecard across the state for both years she has been in office. Some lowlights of her time as an elected official include the following: skipped voting on a bill to monitor noxious pollutants in neighborhoods that have been linked to asthma and cancer (SB 674); skipped voting on a bill to reduce toxins in everyday packaging (AB 2761); and skipped voting on a bill to protect Californians from inflated utility prices by requiring the comparison of rates to actual costs (AB 2666).

But Assembly Member Soria has also failed on other progressive issues, especially those related to protecting workers. In 2024, she skipped both voting on a bill to improve employment standards for janitorial labor in the state (AB 2364) and voting on a bill focused on establishing more protections against workplace violence (SB 553). While Soria has every reason to be a voice for a healthier and more resilient California, she has actively chosen corporate polluters over her communities. Thus, she has been named a “Dirty Dem.”

Greenpeace USA is part of a global network of independent campaigning organizations that use peaceful protest and creative communication to expose global environmental problems and promote solutions that are essential to a green and peaceful future. Greenpeace USA is committed to transforming the country’s unjust social, environmental, and economic systems from the ground up to address the climate crisis, advance racial justice, and build an economy that puts people first. Learn more at www.greenpeace.org/usa.