How would you feel if your daily commute seemed like a challenge? If you had to jump through hoops just to ensure you reached your workplace on time and did not lose wages in a job that already pays you lesser than the stipulated amount? How would you feel if the basic bus charge also seemed too expensive to afford? We listened to the captivating and heartbreaking stories of women low-wage labourers in the textile manufacturing district of Bengaluru, and their fight to reclaim what is theirs.

It was a sense of deja vu to see groups of women, laughing and walking towards the Garments Labour Union office in Laggere. Usually, they are seen rushing towards their factories, impatient and anxious to make sure they get to work on time. This time however, it was different. On a warm Sunday morning in March they were coming together to tell stories and listen to each other about how they commute to work.

It was surprising to see that nearly 150 garment workers actually responded to our call and were sitting together, keenly discussing how they travel to work. It was their personal stories that I was listening to, as much as it was also the labour history and environmental history of the city of Bengaluru. Their modes of commute are diverse. They walk – sometimes even 3 kms, they use factory transport (which they pay for), sometimes they ride BMTC buses or even autos. Many of them talked about how unaffordable and unreliable most of these means were and often it meant they got to work late and lost wages. The roleplay they presented about the rush to get to work in the morning left all of us a bit breathless as they portrayed the efforts they had to make just to get to work on time.

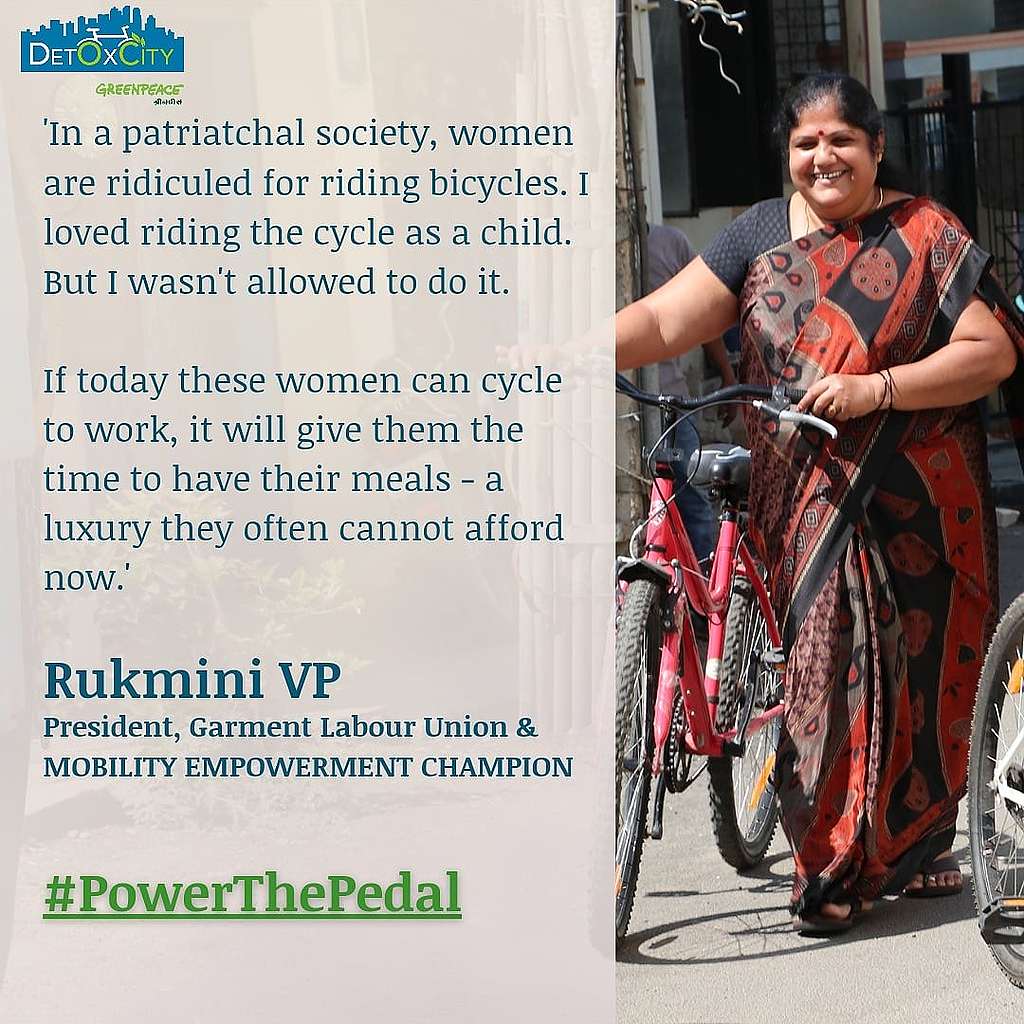

A question about why they don’t cycle got them totally animated. Some of them giggled nervously, some looked incredulous, some of them were excited. It set off a series of hilarious stories of learning to cycle, falling, stealing cycles from siblings, with some it was anger at not being allowed to cycle because they were women.

They were hopeful that cycling would make them free, give them a sense of control over their time, avoid long walks and haggling with auto drivers(who often refused to take them to their factories), save them the expense and make their road to work a little easier. Many of them who had never cycled before signed up for cycling workshops, others offered to be teachers.

As I sat there listening to them, I was struck by the invisibility of nearly 5 lakh women and their long and winding road to work. Their excitement with cycling was also not just about the affordability of it, but also their commitment to being agents of change in the city. A commitment that showed that as low-wage earning communities their preoccupations were not just about survival, but also about a better cleaner, quieter, happier city with better air and streets that are safe and accessible to women.

Now the ball is now in our court – can we find the resources to enable them to use cycles? I can feel the excitement as we dream together of 5000 women out on cycles reclaiming the streets, their lives, their neighbourhoods and their city.

(Benson Issac, Program Director, Greenpeace India)