Amy Moas traveled more than 3,000 miles to one of the last intact forests in North America, the boreal forest of Canada. There, she got a first-hand look at the struggle to save the Cree Nation of Waswanipi land from industrial logging. This is what she saw.

A metal-hulled outboard motorboat took me the last two hours of my three-day journey to one of the last intact forests in North America, in Canada’s Boreal forest. In the end, I traveled more than 3,000 miles, including a substantial amount of time in a white van with a poor suspension system, experiencing every bump on some very long and bumpy logging roads.

After that long journey — which also included two flights, a 20-hour drive, and a helicopter ride — I finally reached the traditional lands of the Waswanipi Cree First Nation. I stood where few humans have ever stood, in one of the last intact forests, in the Broadback Valley.

I made this journey alongside the Cree because even its incredible remoteness has not protected this forest from exploitation.

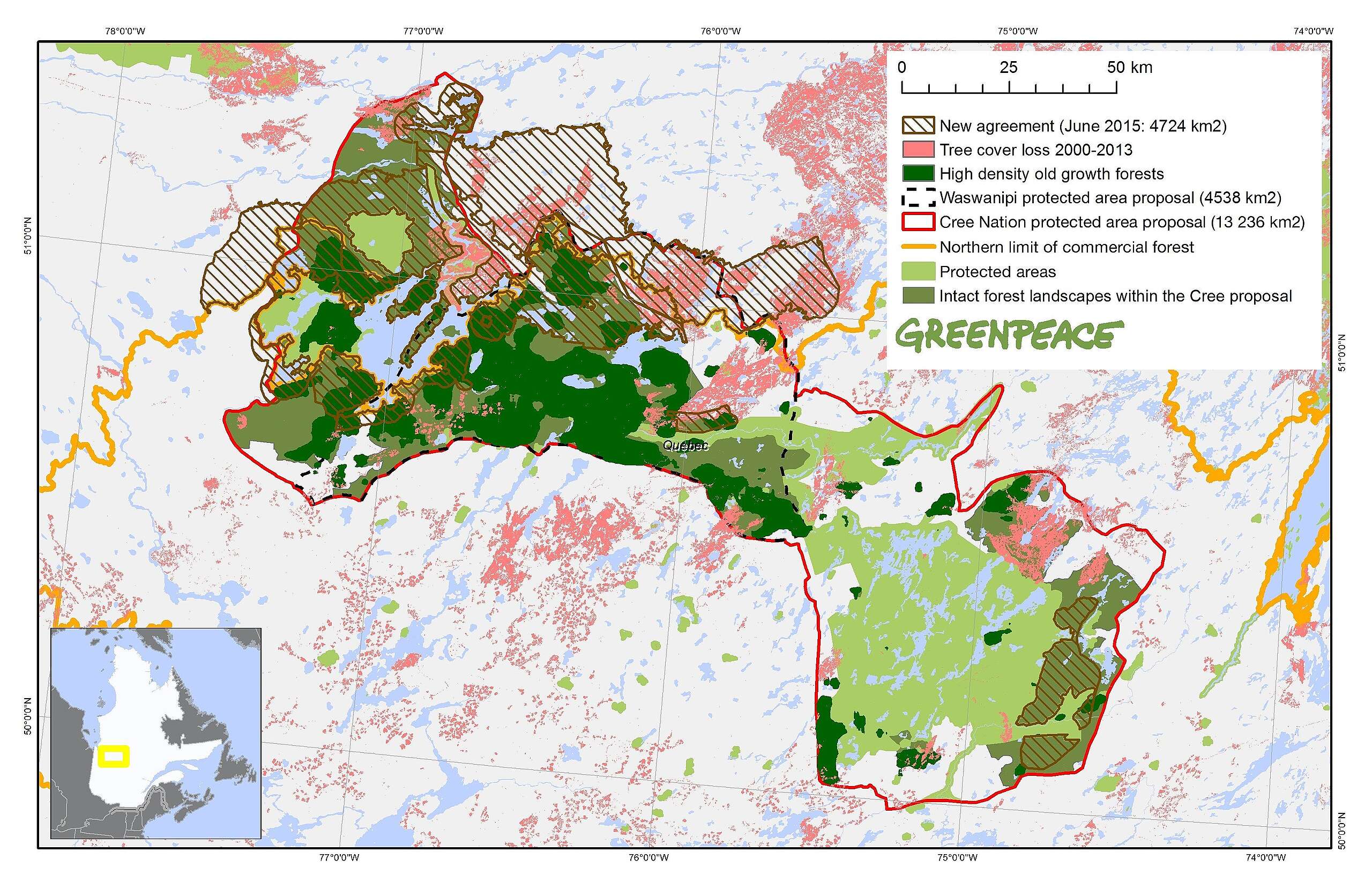

I endured these three days of intense travel with a mission: to reach one of the last intact forests in Canada, help the Waswanipi Cree First Nation shine a light on the threats to this special place and amplify their leadership in protecting it. 90 percent of the Waswanipi Cree territory has been logged and fragmented. They are simply asking to leave the last 10 percent alone and intact.

Map showing intact forest and areas of tree cover loss in Waswanipi Cree territory, as well as a proposal for new protected lands. Map by Greenpeace.

By definition, intact forests have no roads, clearcuts, or powerlines, but that does not mean they are devoid of human presence. Quite the contrary — the forest where I stood had been cared for and harvested by the Cree for generations.

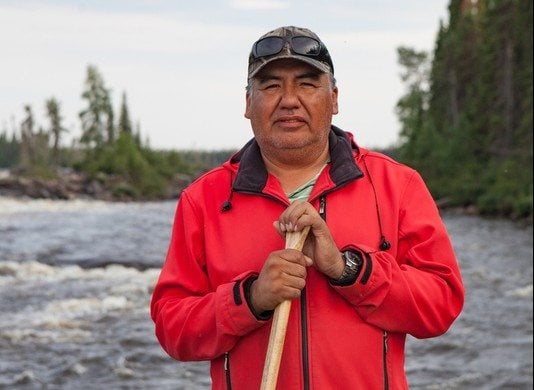

The pristine, clear water, miles of dense forest, bald eagles overhead and moose and bear along the shores — all of this special place is at the heart of Cree culture. This is the land the Waswanipi Cree community have fished and hunted on for generations. Elders in the community — including Don Saganash, one of our hosts — each manage areas of this forest delineated by traplines.

This is a healthy place, shaped by local knowledge and stewardship over time. Clearcut logging threatens a connection to this land forged over thousands of years.

Despite its remote location, logging companies in Canada are eager to log here, including Don’s trapline, where I stood just weeks ago.

Don Saganash’s father hunted and practiced his traditional way of life here and Don hopes to pass this trapline to his son. Now he’s not sure that he’ll be able to. Don has repeatedly stood up to ambitious logging companies and has said no to their expansion plans. He was offered money and gifts in exchange for his sign-off and still said “my land is not for sale.”

He says he will “stay here forever” to fight for the protection of his forest until the end.

Greenpeace has had a relationship with Don and the Waswanipi Cree for years. We proudly stand in support of the entire Cree community calling for the protection of their land. The elders withholding consent has been enough so far to keep their forest standing.

But the Cree have petitioned the Quebec government to permanently protect their land, to stop the onslaught of logging companies from trying to infiltrate. The Quebec government recently protected other lands nearby, but not here. Until this land is safe — and safe for good — the fight against exploitation and for traditional culture will continue.

Lessons I Will Carry With Me

My week with the Cree was intense in many ways. As with my long journey there, I had three long days of travel heading back in which to reflect.

The first thing that I will carry with me is how important it is to keep intact forests safe. There are plenty of quantifiable reasons to keep a forest — for wildlife and for the carbon they store that would otherwise add to our climate crisis. But more than that, these are areas where the Cree are able to thrive and practice their traditional culture. Without the forest, they will lose so much more than the trees, they will lose their identity.

There is a special kind of pureness and beauty that only intact forests hold. These are places that hold the future for the Cree people. It was emotional to stand somewhere so purely beautiful and at the same time experience heartbreaking sadness as I fear this place will not exists for Don Saganash’s children and my children both to see.

The second thing I will carry with me is more personal. I proudly stand up next to the Cree. I was humbled by their welcome and am proud to share their story. These are people that have overcome tremendous hurdles to protect their identity. They deserve to live their lives and thrive. They deserve to have a say on what happens to their traditional land.

I will work hard to be a good ally, advancing their story and their future. The kind of person I want to be is one that will not sit idly by as the Cree fight. I want to be the person that stands next to them and does all that I can.

I will also carry with me immense gratitude for our hosts. I am grateful to Stanley, who made his hunting camp on Lake Quenonisca available to us; to Stanley, Don, and the entire team from Waswanipi, who were patient and knowledgeable as they watched us Greenpeacers scurrying around and delicately pointed out the more effective way to cut a log, catch a fish, or start a fire.

I’d say they have a few stories themselves to tell.

Most of all, I will carry with me gratefulness that places like the Broadback Valley in the Canadian Boreal forest still exist and that Indigenous People like the Waswanipi Cree are still there. Our world is safer, healthier and richer because of them.

Amy Moas is a senior forest campaigner for Greenpeace based in Las Vegas and San Francisco.