This blog is a collaboration between two Greenpeace USA supporters based in Oxnard, California. The story we are about to tell is a violent and potentially triggering one. Much of the information outlined here, told to and relayed by the authors, comes from first-hand accounts of the people in attendance and/or a recounting by their family members. Their names and other information have been changed for privacy.

The events that follow are something that pain us to recount, even weeks later.

Last month, on July 10, two farms on the central coast of California were simultaneously raided by United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Both were Glass House Farms – one in Carpinteria and one in Camarillo, just outside of Oxnard. The month prior, on June 10, ICE attempted to raid the farm in Camarillo, but was stopped by security, who rightfully barred them from entering private property and requested they come back with a warrant. These words came back to haunt them – exactly one month later to the day, ICE came back with a warrant.

The day was a blur. We drove on a small highway that cuts through endless fields, before turning on a small dirt road to a cluster of cars. As we arrived, we were greeted by tear gas and children’s screams. Many of these kids were waiting for family members who were trapped inside of their workplace, all the while inhaling the mysterious gas. I witnessed a little girl vomiting after being exposed. A local professor got arrested after kicking a tear gas canister out from under the wheelchair of a woman.

ICE lined up on the small road that leads to the farm, blocking any protestors from reaching their family members. Meanwhile, groups of ICE agents were inside, allegedly torturing workers. Other agents reportedly beat up people who were hiding. They threw tear gas in the building’s air vents as workers cowered in fear inside; they turned off the air conditioning; they made people delete any footage off of their phones prior to being allowed outside. One worker, Jaime Alanís Garcia, died days later in the hospital due to his injuries related to the raid. Jaime was the main breadwinner for his family here and in Mexico.

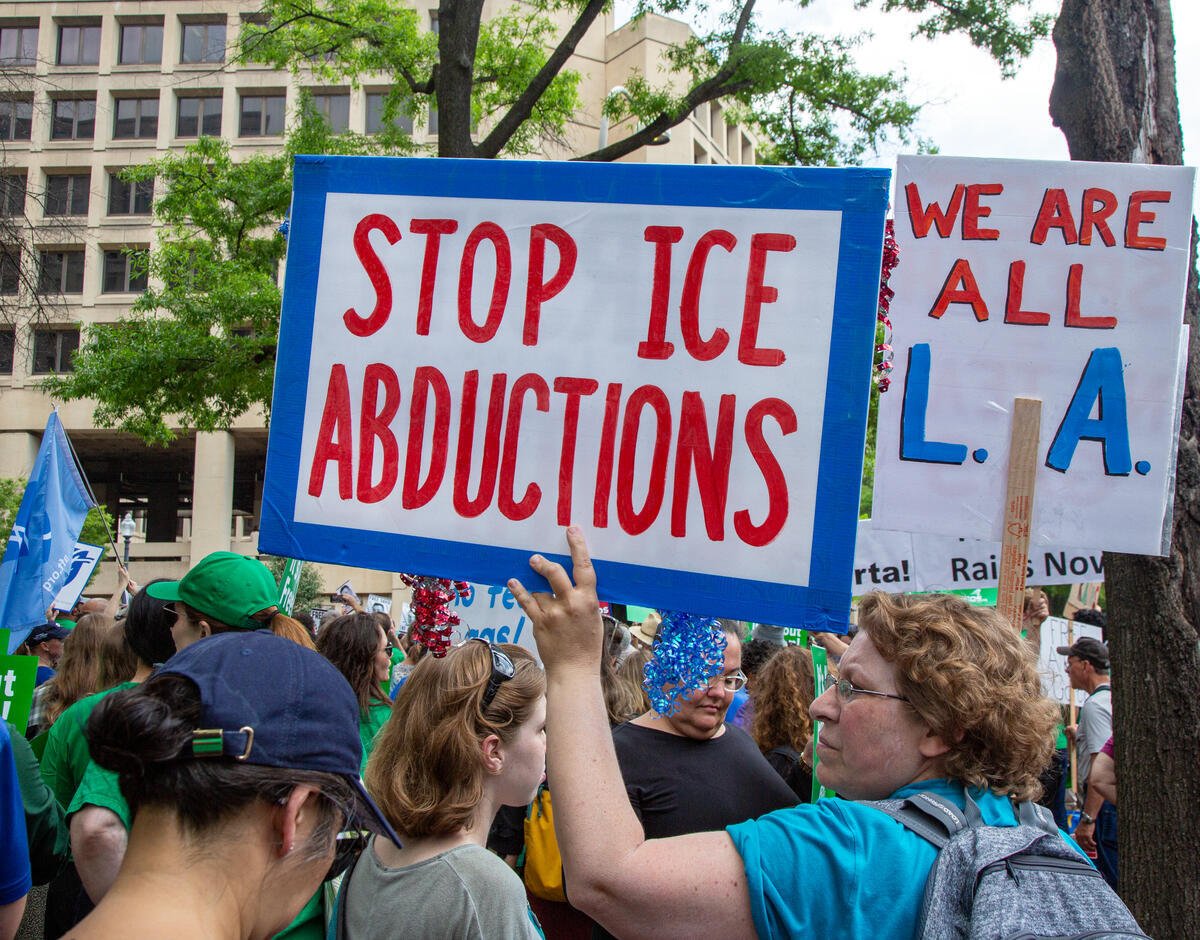

The crowd was trying to hold its own line on the dirt path to prevent any vehicle – other than medical or fire – from entering and any ICE vehicle containing workers from leaving. The crowd began to chant at the agents, “Quit your job! Quit your job!” No reaction. Someone looked one of the masked agents in the eyes: “History will remember you for this. You don’t have to do this. Don’t just blindly follow orders until it’s too late.” No response. They robotically deployed more tear gas at the crowd. A man drove a tank by, shooting pepper balls down at the crowd.

Oxnard is an agricultural city in between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. It is 78% Chicane/Latinx. It is the leading strawberry producer in the United States, and plays a crucial role within California’s strawberry industry, shipping millions of strawberries worldwide. The city is a vibrant community with a long history of labor struggles and resistance between the Asian and Pacific Islander (API) and Chicane communities – like the historic 1903 Oxnard sugar beet strike, a joint effort between Japanese and Mexican workers who formed the Japanese-Mexican Labor Association (JMLA). The strike, which began in February 1903, saw 1,200 workers participating and led to a near-complete shutdown of sugar beet farming in the area as they protested against exploitative labor practices by the Western Agricultural Contracting Company (WACC). The strike is notable for its cross-cultural solidarity and its impact on the American labor movement.

Many of the farmworkers here in the central coast are Mixteco, mostly from the state of Oaxaca, Mexico. Some of them speak only Mixteco, a language whose roots can be traced back to around 10,000 years ago – eons older than the United States and the English language. Most of them have been displaced from their ancestral homelands, and many of them have moved from plantation to plantation since they were children to find work, often ending up here in Oxnard.

Earlier in the day, we had joined a call about, ironically and fittingly, the intersection of climate change and immigration. The topic is becoming more and more popular these days – but what do “climate justice” and “intersectional issues” really mean? What does it mean to contextualize this fascistic rise in brutal deportations within the environmental justice movement? According to the World Resources Institute, “Indigenous Peoples and local communities hold or manage 54% of the world’s remaining intact forests.” What does it mean for the environment if hundreds of thousands of Indigenous people are kicked off their land and out of their rivers, and the earth has been poisoned with chemicals?

The North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA, was signed into law on December 8 1993 and took effect on January 1, 1994. A year prior to NAFTA’s implementation, however, the Salinas government violated one of the most sacred articles in the Mexican Constitution and privatized communally held lands, known as ejidos. It was no coincidence that after the passing of NAFTA, these lands were taken from small farmers and given to megacorporations – the same ones that poison the streams, the earth, and the air.

Logically, the effect of displacement is migration. Many displaced peoples migrated inside of Mexico, and many came to the United States looking for survival. Migration from Mexico to the United States was around 350,000 per year before NAFTA – it was around 500,000 per year by the early 2000s.

Fast forward to Camarillo on July 10, 2025, when ICE terrorized the very people who were displaced from their homelands. The United States is using our tax dollars to throw tear gas at children and deploy military tanks to a farm. Why does it seem like the government has endless money to fund tanks, tear gas, and pepper bullets to deploy at unarmed civilians who are just trying to make sure their loved ones can come home safely after a long day’s work? Why isn’t this money instead going toward clean energy, green jobs, and equitable healthcare? Why does it seem that the government always has endless money for violence, but we are barely able to fund crucial programs for our collective wellbeing?

We then went to Carpinteria’s town hall meeting, where we were met with an overwhelming crowd. The joy of seeing so many community members out there and the intensity of the day began to hit us. This joy was swiftly interrupted by calls from people back at the farm asking for assistance.

We returned to Glass House where the crowd was now bigger, and the National Guard was now there helping hold the line. Most of the officers were Brown and seemed young – almost too young to be there. To us, it seemed like most of them did not want to be there, standing off against their own communities. We saw something in their eyes: could it be confusion, pain, anger, or a longing to be on the other side?

“Quit your job!” The crowd kept chanting. We hope they considered it, though we know they are just following orders. Rank-and-file Nazis were also “just following orders.”

We’ve been asking ourselves: how far can humans be pushed? What horrors in humanity have been committed because people blindly follow orders? Fleeing slavery, being Jewish, even opening a bank account as a woman have all been illegal in our not so distant past. The law, while binding, cannot always be our guiding light towards moral truth.

We urge everyone to critically analyze this historical conjuncture. What historical parallels can we find in this emerging moment? What should we do to prevent future atrocities? What does it mean for the environmental and climate movement if it turns a blind eye to the displacement of peoples from their lands?

This year alone, we saw the construction of Alligator Alcatraz, a detention center that was built in a mere eight days and will cost taxpayers around $450 million annually to operate. The project was built on sacred Miccosukee land, but according to the developers, this land was “empty.” There have been reports of inhumane conditions. We also saw the conversion of the Los Angeles Immigration Detention Facility, which has been a prison since 1999, into a large-scale immigration detention center. We have heard first hand reports from inside this facility that the rooms are so frigid, people sign self deportation orders just to escape. People rarely get fed. People do not get access to their medications. One of the detainee’s wives told us that her husband had called, telling tales of his own broken jaw and other physical abuse by agents.

We are seeing history repeat itself in front of our eyes. If we don’t fight this now, when will we? We can’t wait until it’s too late!

We’ve both kept hearing the haunting refrains of this poem recently:

First they came for the Communists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Communist

Then they came for the Socialists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Socialist

Then they came for the trade unionists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a trade unionist

Then they came for the Jews

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Jew

Then they came for me

And there was no one left

To speak out for me

The poem by German Pastor Martin Niemöller, written in 1946, reminds us that any resource going towards the violence and pain of anyone is a resource taken away from all of our collective wellbeing. What does it mean to make their struggle our struggle? Are we going to stand by and watch as the hardest workers in our communities – who are already facing the worst effects of climate change – get kidnapped? What are we fighting for if not each other?

These are not separate struggles and it’s on us to fight back against this in whatever capacity we can. We need everyone in this together – and there is a role for each one of us. You can join your local rapid response network, help with your local food distribution network, help distribute useful information, join Greenpeace USA, and donate to your local mutual aid network. The more we comply with this abuse, the more this administration will continue to get more aggressive. It can be easy to fall into a hopeless despair, but we have more agency than we think.

We urge you to take your power back and stand up for the things in which you believe. Any small step is better than none.

They won’t stop with immigrants. This moment is a threat to our shared humanity.