Nuclear

Greenpeace has always fought – and continues to fight – against nuclear weapons and nuclear power because it is an unacceptable risk to the environment and to humanity.

Nuclear free New Zealand

Here in Aotearoa, we fought hard for our nuclear-free status. We stood against nuclear testing in the Pacific. We refused visits from nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed ships. And in doing so, we led the world.

In March 1976, over 20 anti-nuclear and environmental groups, including Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth came together to form a loose coalition called the Campaign for Non-Nuclear Futures (CNNF).

The coalition’s mandate was to oppose the introduction of nuclear power and to promote renewable energy alternatives.

In 1984, Prime Minister David Lange banned nuclear-powered or nuclear-armed ships from using New Zealand ports or entering New Zealand waters. Under the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987, the territorial sea, land and airspace of New Zealand became nuclear-free zones.

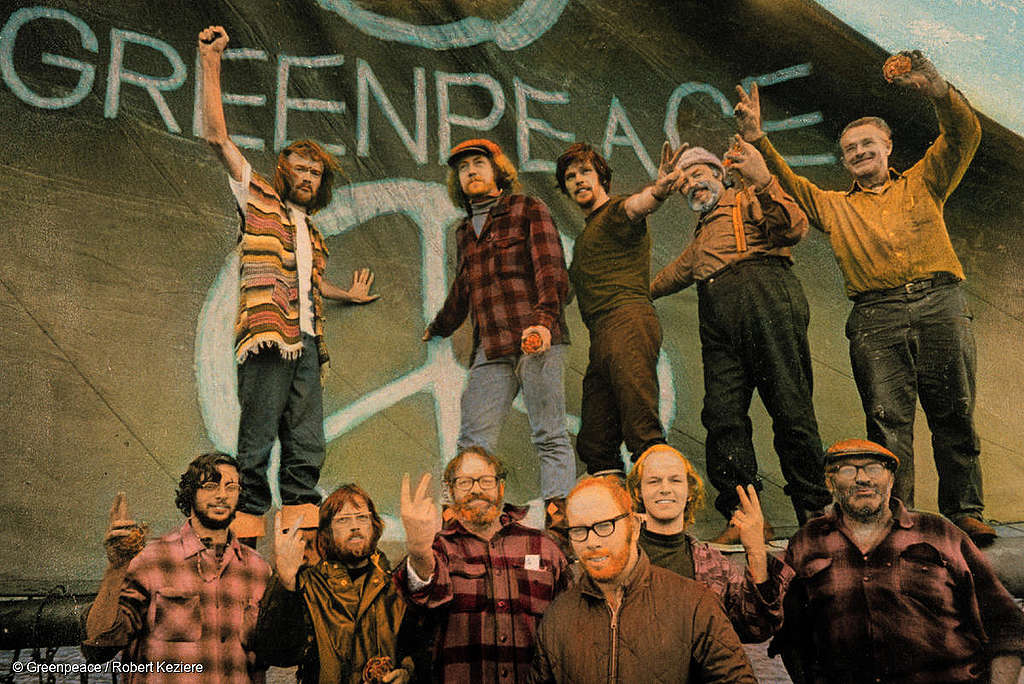

The Nuclear Campaign was Greenpeace’s first campaign in New Zealand. It initially grew out of the anti-nuclear and anti-war movements of the late 1960s, especially in Canada, where there were large numbers of anti-war US draft resisters and a large student movement that mobilised against US involvement in the Vietnam War, and nuclear weapons testing in the Aleutian Islands.

Nuclear power

Nuclear power is touted as a solution to energy problems, but in reality, it’s complex and hugely expensive to build. It also creates huge amounts of hazardous waste. Renewable energy, like wind and solar, is cheaper and can be installed quickly. Together with battery storage, it can generate the power we need and slash our emissions.

Nuclear power is incredibly expensive, hazardous and slow to build. It is often referred to as ‘clean’ energy because it doesn’t produce carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases when electricity is generated, but the reality is that it isn’t a plausible alternative to renewable energy sources.

Nuclear energy is also dangerous.

We’re still living with the legacy of radioactive accidents at Chernobyl and Fukushima, and nuclear test radiation in the Marshall Islands. Nuclear power creates radioactive waste at every stage of production, including uranium mining and reprocessing of spent reactor fuel. Some of this waste will remain dangerously radioactive for hundreds of thousands of years, yet nobody knows of a way to safely store it.

Instead of backing nuclear power, world governments need to invest in renewable energy including wind and solar power. A thriving renewable energy industry will create jobs, provide cheaper electricity and help cut emissions much faster than nuclear power.

Nuclear weapons

In recent decades, there has been some progress towards ridding the world of nuclear weapons. But nuclear disarmament is still a long way off, and conventional wars still trap millions of people in ugly conflicts.

For a truly peaceful planet, we need to dispose of all weapons of mass destruction and focus on more peaceful objectives, such as renewable energy and responding to the climate emergency.

At the height of the Cold War in the 1960s it seemed almost inevitable that a terrifying nuclear arms race would spread to all corners of the globe, threatening the future of humanity.

In the 1970s and 80s, Greenpeace campaigned for a ban on nuclear testing and helped relocate the people of Rongelap to Mejatto Island after decades of nuclear testing. It was after this final mission in 1985 that the French government ordered the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior whilst in New Zealand. After years of campaigning, a ban was achieved and ultimately the international community got together and agreed to ban nuclear weapons.

Fifty years on, almost all nations reject the need for nuclear weapons. Today only nine countries still possess them in clear contravention of international law (USA, Russia, China, UK, France, Israel, Pakistan, India and North Korea). But sabre rattling between posturing world leaders has increased the risk of nuclear conflict. Experts say the risk is greater than it has been in nearly 70 years.

The nuclear states’ obsession with nuclear weapons also diverts attention away from the biggest security threat of all – climate change. Our basic needs – food, water, shelter and energy – are being threatened by a rapidly changing climate. Left to fester, these problems pose a very real risk to global peace and security.

Spending endless billions on nuclear missiles is a costly diversion from tackling the real challenges we face today. And what do we gain? Bombs capable of flattening cities clearly can’t deter suicide bombers, deal with cyber-terrorism or prevent civil wars.

Despite the current political situation, more and more security experts and senior military figures now agree that a world free from nuclear weapons is both achievable and essential. And more people are realising that those few countries clinging onto nuclear arms are making the future more dangerous for both their own citizens and the rest of the planet.

But for the vast majority of countries and people around the world – peace is on our side.

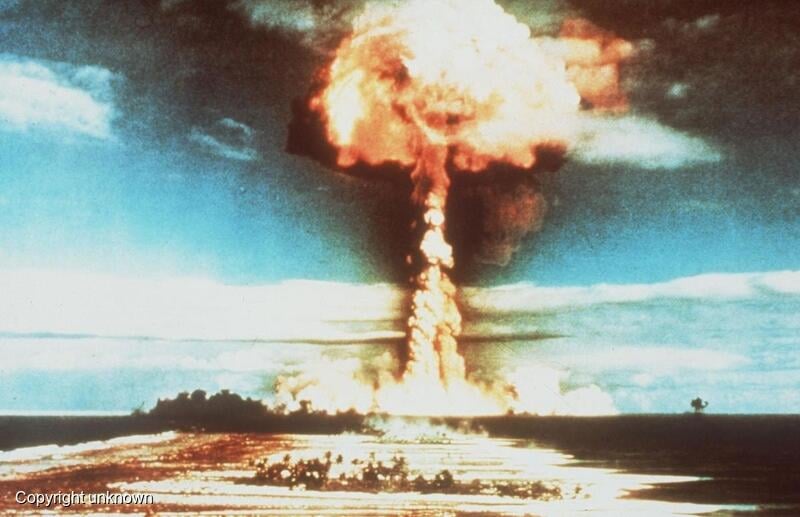

Pacific nuclear testing

Despite a name suggesting peace and tranquillity, there were around 325 nuclear weapons detonated in the Pacific region by the governments of France, Britain and the USA between 1946 and 1996. The total cumulative explosive yield was about 173.8 megatons, which is the equivalent of about 11,600 Hiroshima bombs.

As a result of the massive amount of radioactivity released by the atmospheric tests spreading across the globe, it has been estimated that there were about 430,000 additional cancer deaths globally due to cumulative radiation doses by the year 2000.

It’s a legacy that remains to this day for many people in the Pacific.

Greenpeace is 100% independent

We take no money from corporations or governments. Our ability to speak and act freely is our greatest strength. We rely on donations from people like you, people who care about protecting the planet. Please donate today to help power our work to build a more green and peaceful future.

Keep up to date with our work to rid the world of nuclear power and nuclear weapons

-

How we restore sanity in a world of nuclear madness

Last week, US President Trump instructed the Pentagon to immediately start matching other nuclear weapon states in their testing of nuclear weapons, particularly Russia and China.

-

Forty years of resistance in the Pacific

On 10 July 2025 in a dawn ceremony led by Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, we commemorated the 40th anniversary of the state-sanctioned bombing of the original Rainbow Warrior in Auckland, and…

-

40 Years on: The Legacy of the Rainbow Warrior & Indigenous Resistance

Forty years after the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior, the spirit of resistance sails on. From anti-nuclear activism to climate justice, the push for transformation is inextricably tied to tino…

-

Fortieth anniversary of the Rainbow Warrior bombing

On July 10, 1985, at 11:48 p.m. and 11:51 p.m., two extremely powerful bombs planted by the French secret services sank the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland Harbour in…

-

You can’t sink a rainbow and you can’t silence hope

40 years since the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior.

-

Greenpeace holds dawn commemoration of 40 years since Rainbow Warrior bombing, death of photographer Fernando Pereira

Greenpeace held a dawn ceremony to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Rainbow Warrior bombing and the death of Fernando Pereira.

-

Greenpeace International begins groundbreaking Anti-SLAPP case to protect freedom of speech

In a landmark test case of the European Union’s new legislation to protect freedom of expression and stop abusive lawsuits, Greenpeace International has overnight challenged the US oil pipeline company,…

-

A defining moment in history: 40 years ago, the Marshall Islands fought to protect their future and defied the US

This is the story behind “Operation Exodus” – a ship called Rainbow Warrior and an island community, versus a huge colonial power that discredited the act as “manipulation” for Greenpeace’s anti-nuclear agenda.

-

France spent €90,000 to discredit the impact of Pacific nuclear testing – Greenpeace response

New documents obtained by investigative outlet Disclose suggest that France spent €90,000 to discredit research into the impacts of its nuclear testing in the Pacific.

-

French authorities block Greenpeace ship from participating in UN Ocean Conference

French authorities have blocked Greenpeace International’s ship Arctic Sunrise from entering the port of Nice, where the “One Ocean Science Congress” and the UN Ocean Conference are being hosted. This…