Living toxic-free

Creating a world free from harmful toxins in our environment and in our lives.

We’re working towards a toxic-free future for all

We all deserve to live our lives free of the harmful impacts of toxic chemicals. Whether by pushing for safer chemical plants or detoxing the clothing we wear every day, we’re working towards a toxic-free future for all.

Toxic chemicals have no place in our homes, our clothes, or our food. And yet there they are, polluting our water, air and soil and threatening our health.

Toxic emissions from chemical plants, waste dumped into our water sources, and the chemicals in our clothing are all unseen but serious threats to our well-being. For the one in three Americans living in close proximity to hazardous chemical facilities, the threat of a major disaster looms large.

Protecting people from the harmful impacts of toxic chemicals is key for the health and safety of communities everywhere. That’s why we’re fighting locally and globally to remove toxic chemicals from the lives of millions.

The Time Is Now to Stop Chemical Disasters

Roughly 110 million Americans live, work, and go to school in a potential chemical disaster zone — 466 chemical facilities each threaten more than 100,000 Americans, and at least one in every three schoolchildren attends school near a chemical facility. There have been more than 355 chemical incidents since the fertilizer explosion in West, Texas in April 2013 that killed 15 people and injured more than 200.

But the solutions for safer chemical facilities exist, and we can achieve them without sacrificing jobs. As of 2010, 554 chemical plants have changed their practices, swapping in safer chemicals and adopting new safety procedures. Thousands of facilities, however, still lag behind.

Our goal is to protect all communities from the preventable horror of a chemical disaster.

Detoxing Industry

The multi-billion dollar corporations that produce our clothing are some of the biggest polluters out there.

Every year, the fashion industry pollutes waterways in places like Mexico, China, and Indonesia by using hazardous chemicals in the manufacturing plants. Those same toxic chemicals are present in our clothes, too.

Since 2011, we’ve challenged some of the world’s most popular clothing brands to work with their suppliers to stop the flow of toxic chemicals into our waterways. Already, companies like Nike, Adidas, H&M, and more have signed on. Will your favorite retailer?

Toxic chemical pollution affects all of us, but it has the most devastating effects on disadvantaged communities.

Too often, those with the fewest resources to protect themselves are the ones exposed to harmful pollution. In the United States, low-income communities and communities of color are statistically more likely to live in the country’s most polluted neighborhoods. In fact, the poverty rate in the communities living closest to chemical facilities is 50 percent higher than the national average. And at the global level, it’s often developed countries and their industries that dump their hazardous waste in the developing world.

That’s why it’s so important to take advantage of the opportunities we have right now to create a toxic-free world. We’re campaigning to eliminate the risk of major chemical disasters across the country and to end toxic industrial pollution across the globe.

If that sounds like the future you want, join us! Check out the links below to learn how we’re making a difference and how you can join the movement.

Learn more about…

Preventing chemical disasters

Going PVC free

Green electronics

-

New Analysis of Five Major U.S. LNG Export Projects Finds Every One Fails the “Climate Test”

The new analysis shows that U.S. LNG export projects displace renewable energy and drive up emissions – making them incompatible with a livable climate

-

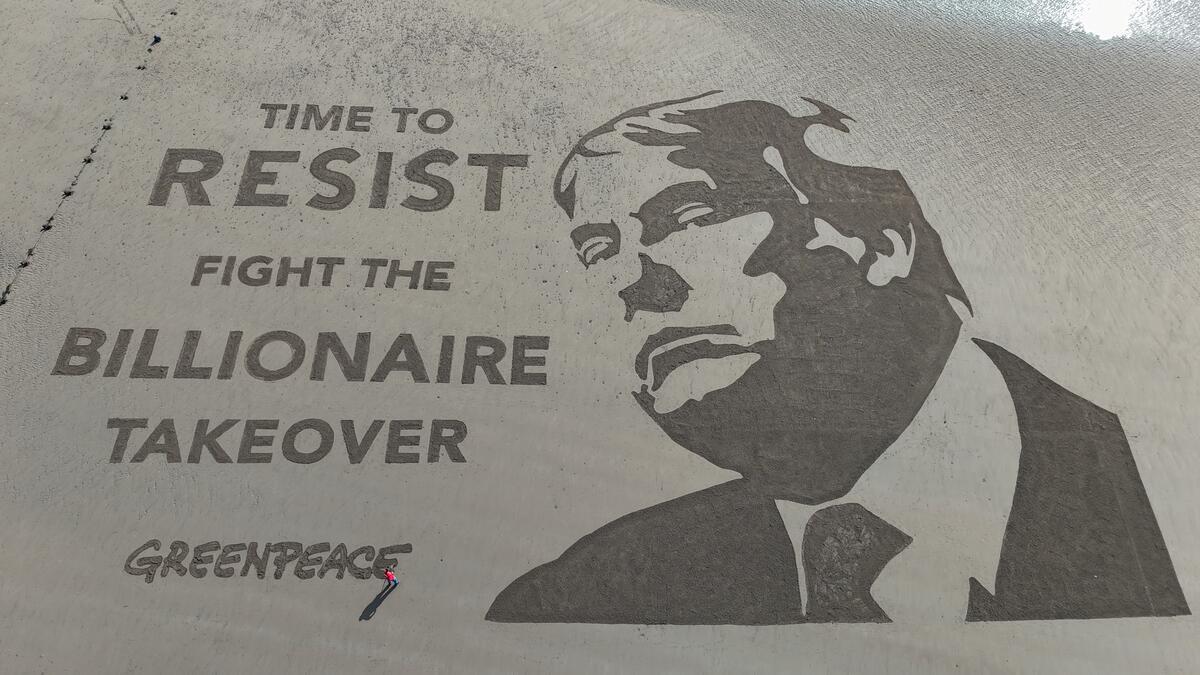

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

A Little Story About the Monsters In Your Closet

A new investigation by Greenpeace has found a broad range of hazardous chemicals in children’s clothing and footwear across a number of major clothing brands, including fast fashion, sportswear and…

-

From Smart to Senseless: The Global Impact of Ten Years of Smartphones

Smartphones have undeniably changed our lives and the world in a very short amount of time. In 2007, almost no one owned a smartphone. In 2017, they are seemingly everywhere. Globally,…

-

Chlorine Bleach Plants Needlessly Endanger Millions

Bleach manufacturers use chlorine gas to produce bleach and also repackage bulk chlorine gas into smaller containers for commercial use. These facilities often ship, receive and store their chlorine gas…

-

A Little Story About a Monstrous Mess

Greenpeace has investigated the hazardous chemical residues present in children’s clothing. A set of 85 clothing items from Zhili Town of Huzhou in Zhejiang Province and Shishi in Fujian Province…

-

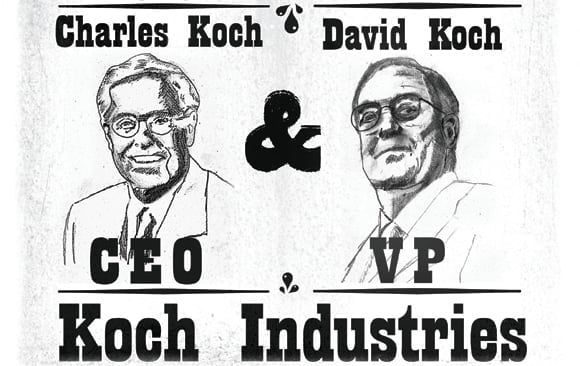

Toxic Koch: Keeping Americans at Risk of a Poison Gas Disaster

In 2010, Koch Industries and the billionaire brothers who run it were exposed as a major funder of front groups spreading denial of climate change science and a key backer of…

-

Greenpeace Security Inspection Report

The facility also has up to 7.6 million lbs of chlorine gas on site that could endanger a similar or larger population in the case of a catastrophic release. It…

-

Chemical contamination at e-waste recycling and disposal sites in Accra and Korforidua, Ghana

The global market for electrical and electronic equipment continues to expand, while the lifespan of many products becomes shorter.

-

Playing Dirty

Analysis of hazardous chemicals and materials in games console components.