-

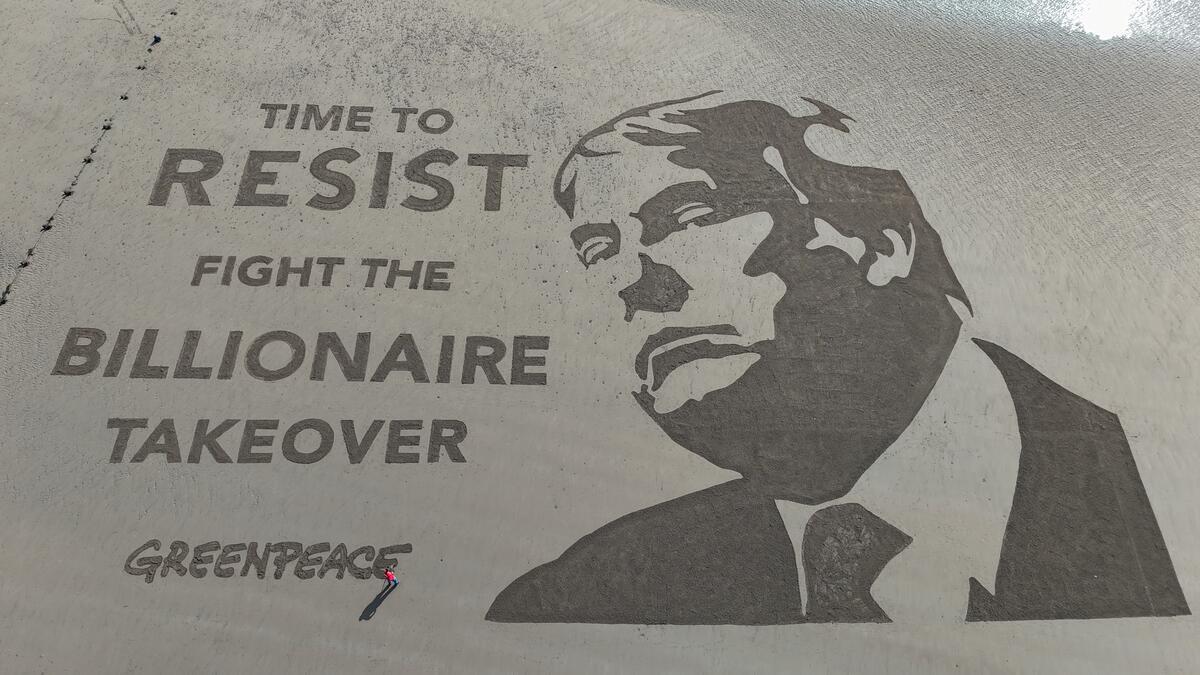

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

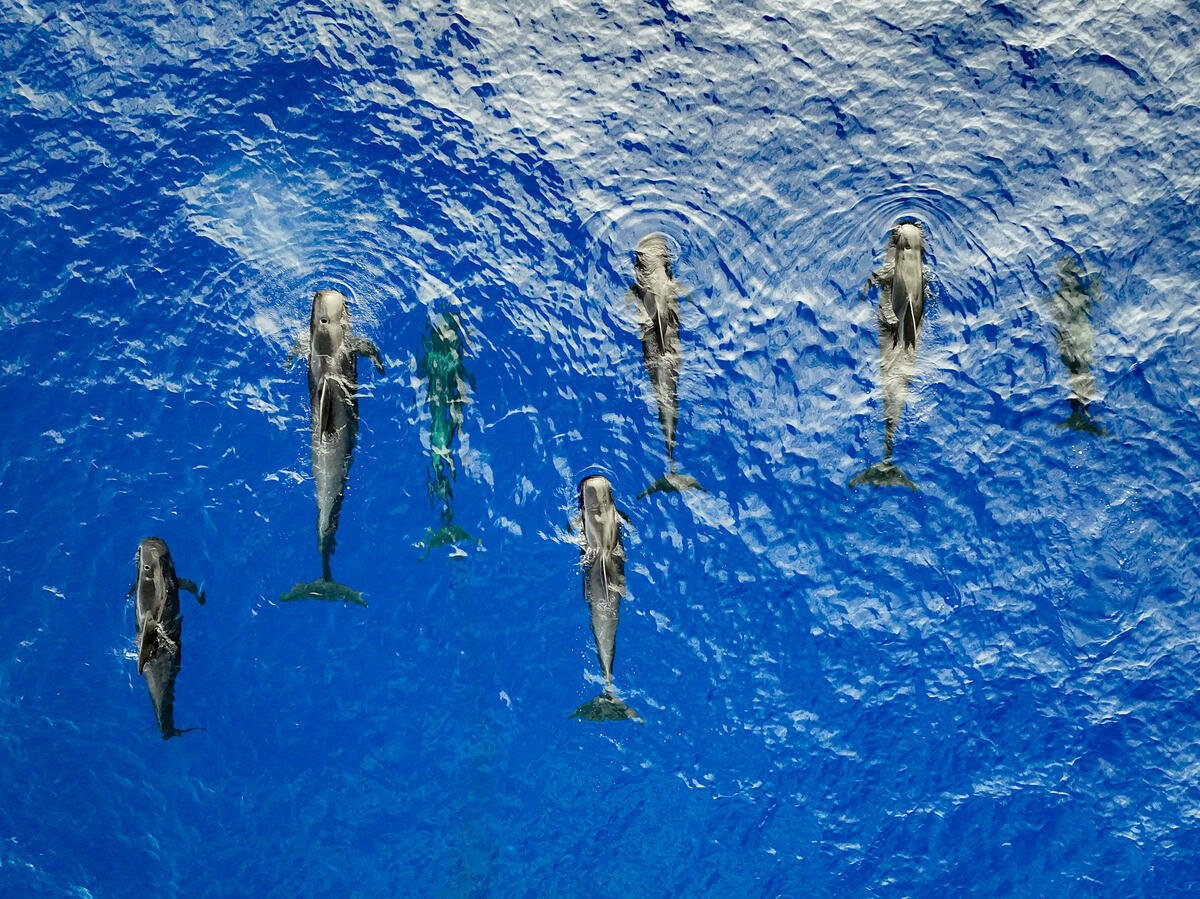

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

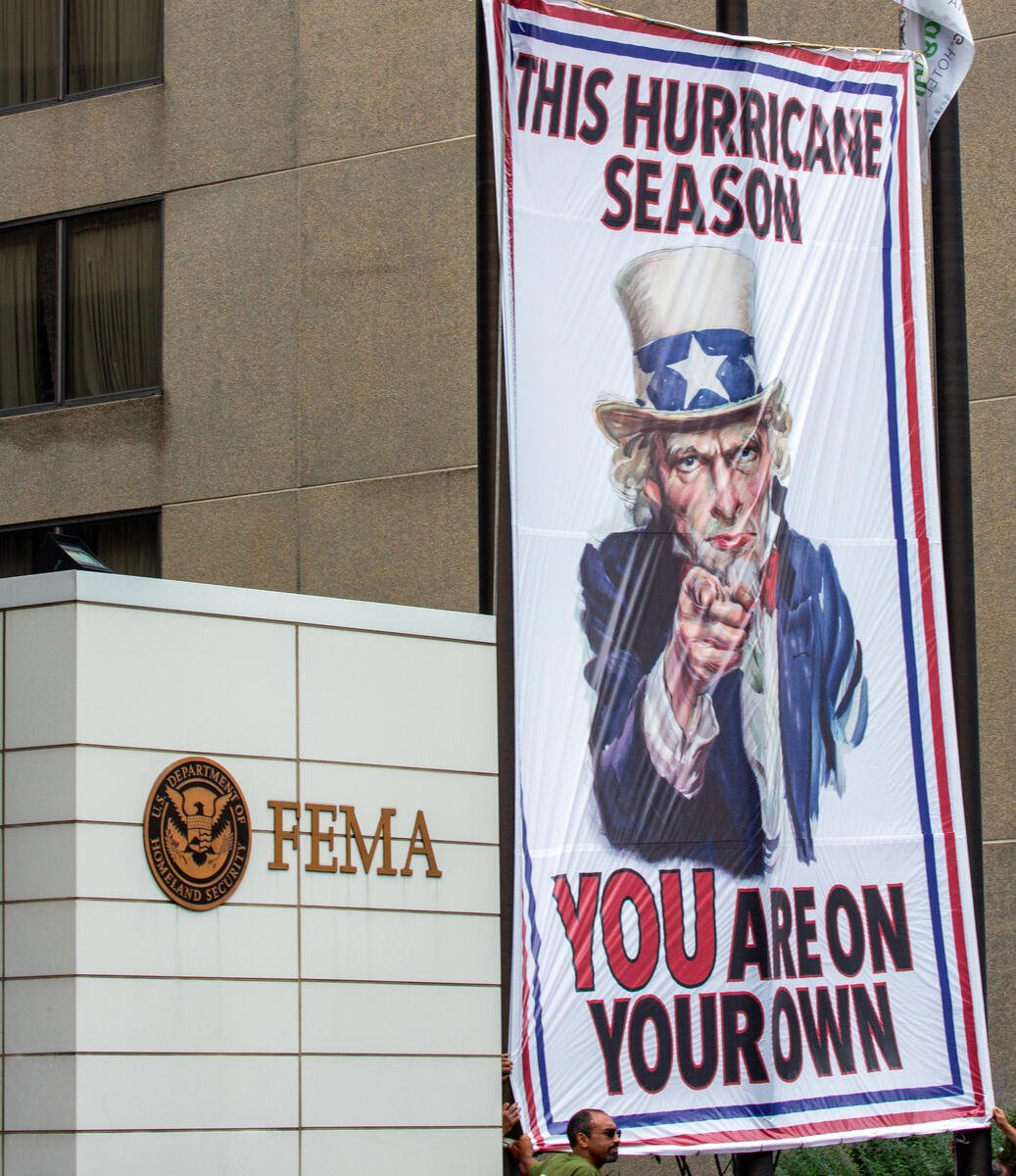

This hurricane season Greenpeace USA helps deliver Uncle Sam’s disturbing message to America

Greenpeace USA deployed a banner at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) headquarters to assist in making Uncle Sam’s message to the country crystal clear: this hurricane season, you are…

-

Greenpeace USA Slams U.S. Seabed Mining Plans off American Samoa

The Pacific is not a sacrifice zone. Its people should not be forced to host a destructive industry they’ve clearly rejected.

-

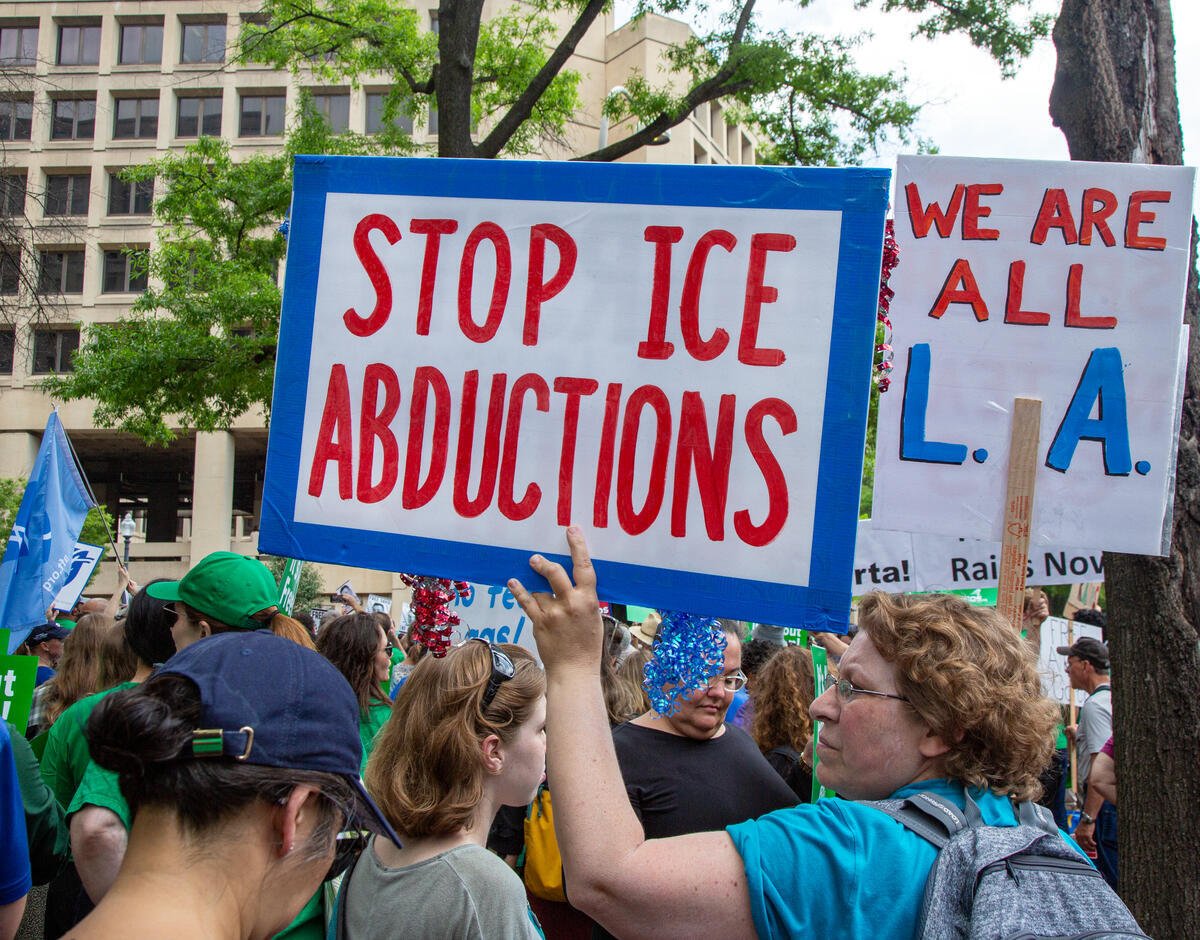

GPUS decries Trump’s fascist response to LA protests

WASHINGTON, DC (June 11, 2025) – In response to the Trump Administration deploying the National Guard on protesters in Los Angeles and the recent detention of David Huerta, President of…

-

OP-ED: Greenpeace USA leadership pose critical questions during UN Oceans Conference

In the op-ed “Who Will Defend Our Oceans—the Last Global Commons?” published in Common Dreams, Greenpeace USA Interim Executive Director Sushma Raman and Greenpeace USA Oceans Campaign Director John Hocevar discuss solutions for how the international community can stop this dangerous rollback before it is too late.

-

Greenpeace comment on opening of UN Ocean Conference

With dozens of Heads of State expected to attend, the conference—co-hosted by France and Costa Rica—offers a crucial opportunity for governments to raise the level of global ambition on a suite of urgent ocean issues, including marine biodiversity, deep sea mining, and plastic pollution that will face key decisions in the coming months.

-

Greenpeace USA’s “Dirty Dems” called out in Capitol Rotunda

Greenpeace USA activists deployed banners in the Capitol Rotunda naming nine Democrats who take large sums of money from the oil and gas industry and receive failing grades on progressive issues.

-

Energy Transfer vs. Greenpeace trial analysis

Here is what you need to know about the Energy Transfer vs. Greenpeace trial.

-

Energy Transfer lawsuit: still no evidence, still no final judgment

Greenpeace defendants again met Energy Transfer in a post-trial hearing in North Dakota.