Defending democracy

A healthy democracy is a pre-condition to a healthy environment

We cannot protect our health and environment without a well-functioning democracy that works for all, especially BIPOC communities who have historically borne the heaviest burden of pollution and voter suppression. Our democracy should represent the interests of the people — interests like a safe climate and a healthy environment. Over the past nine years, Greenpeace USA has worked to defend democracy across a variety of issues. We are currently committed to defending democracy from three perspectives: The Right to Vote, The Right to Protest, and Ending Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (Anti-SLAPP).

47

anti-protest bills enacted in 21 states since Standing Rock

150

people and organizations targeted by the fossil fuel industry with SLAPPs and similar judicial abuses in the past decade

9

of the top ten lobbying for fossil fuel anti-protest bills since 2017 are oil and gas companies

Our democracy is in peril

A handful of extremist politicians and corporations are putting up barriers to silence our voices based on what we look like or where we live. Following a record-setting 2020 election with an unprecedented number of votes cast, we have seen efforts to overturn a free and fair election, violent attacks on the peaceful transition of power, and a coordinated surge in racist voter suppression. This faction of extremist politicians who want nothing more than to return to the Jim Crow era will stop at nothing to gain power.

Corporate attacks on all forms of dissent are coming from many directions. Corporations and special interests are undermining our democracy by funding extremist lawmakers and sponsoring racist voter suppression and anti-protest bills. This has serious implications for our advocacy for a just and sustainable planet. Despite a supermajority of Americans supporting climate action, our democracy allows the fossil fuel industry, at the behest of corporate interests, to actively obstruct climate solutions.

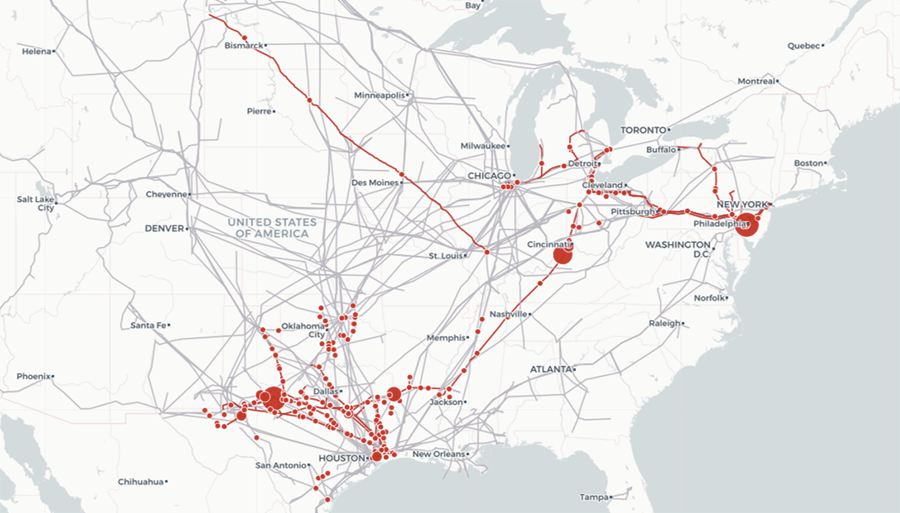

Meanwhile, efforts to protest these issues are met with anti-protest bills and vindictive corporate Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs). Since 2016, broad fossil fuel anti-protest laws have been enacted in 18 states, shielding roughly 60% of domestic oil & gas production and associated infrastructure from peaceful protest that could hinder the industry’s continued growth. Big Oil and its supporters continue to use SLAPPs against individuals and organizations in a concerted effort to shrink civic space and raise the cost of protesting, making it increasingly risky for activists and BIPOC communities to oppose pipelines and other projects that threaten their communities.

We urgently need a people-powered democracy

Defending freedom of speech, protest, dissent, and restoring and improving voting rights, are the first steps along that path. Unless the people have a meaningful check on power, all our other freedoms continue to be put at risk. By unleashing the power of our volunteers and supporters to push corporations, make our voices heard on Capitol Hill, take to the streets in defense of communities, and participate in creative protest, we can build a better future together.

Learn more about…

The right to dissent

The right to protest

Greenpeace USA is committed to engaging legislators to advocate for the passage of anti-SLAPP, right-to-vote, and right-to-protest legislation. We are working alongside a coalition of like-minded groups to defend democracy. Supporters like you can contribute by signing letters, contacting legislators, and actively supporting on-the-ground efforts of groups engaged in this work.

-

New Analysis of Five Major U.S. LNG Export Projects Finds Every One Fails the “Climate Test”

The new analysis shows that U.S. LNG export projects displace renewable energy and drive up emissions – making them incompatible with a livable climate

-

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

Dollars vs. Democracy 2023

Americans overwhelmingly support government action on the climate crisis. As a result, the fossil fuel industry has expanded its playbook…

-

Greenpeace Report: Dollars vs. Democracy

A healthy democracy is a precondition for a healthy environment. When everyone’s vote counts and when everyone’s constitutionally-guaranteed right to peacefully protest…

-

Report: Protecting Science at Federal Agencies

A new report describes “new and ongoing threats to the use of science in public health and environmental decisions…

-

Greenpeace Report: Too Far Too Often

“Too Far Too Often” details the unethical and inappropriate tactics employed by ETP and related companies against opponents of DAPL, and highlights how, in spite of increased global scrutiny and intense criticism of ETP’s tactics at Standing Rock to intimidate and quash opposition, ETP continues to apply many of the same tactics and to display…

-

Greenpeace Report: Contaminating the Courts

Corporations have increasingly begun to resurrect the legal strategy of expanding the concept of corporate personhood to argue that local, state, or federal environmental laws violate their constitutional rights. This trend isn’t totally new, but it has accelerated since the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United v. FEC decision.