Nuclear power is dirty, dangerous and expensive. Say no to new nukes.

Nuclear energy has no place in a safe, clean, sustainable future. Nuclear energy is both expensive and dangerous, and just because nuclear pollution is invisible doesn’t mean it’s clean. Renewable energy is better for the environment, the economy, and doesn’t come with the risk of a nuclear meltdown.

The problem

People are concerned about many issues surrounding the industry: From the risk of accidents and impacts that radiation has on human health, through contamination of environment and radioactive waste, to violation of human rights and links of nuclear energy to nuclear weapons.

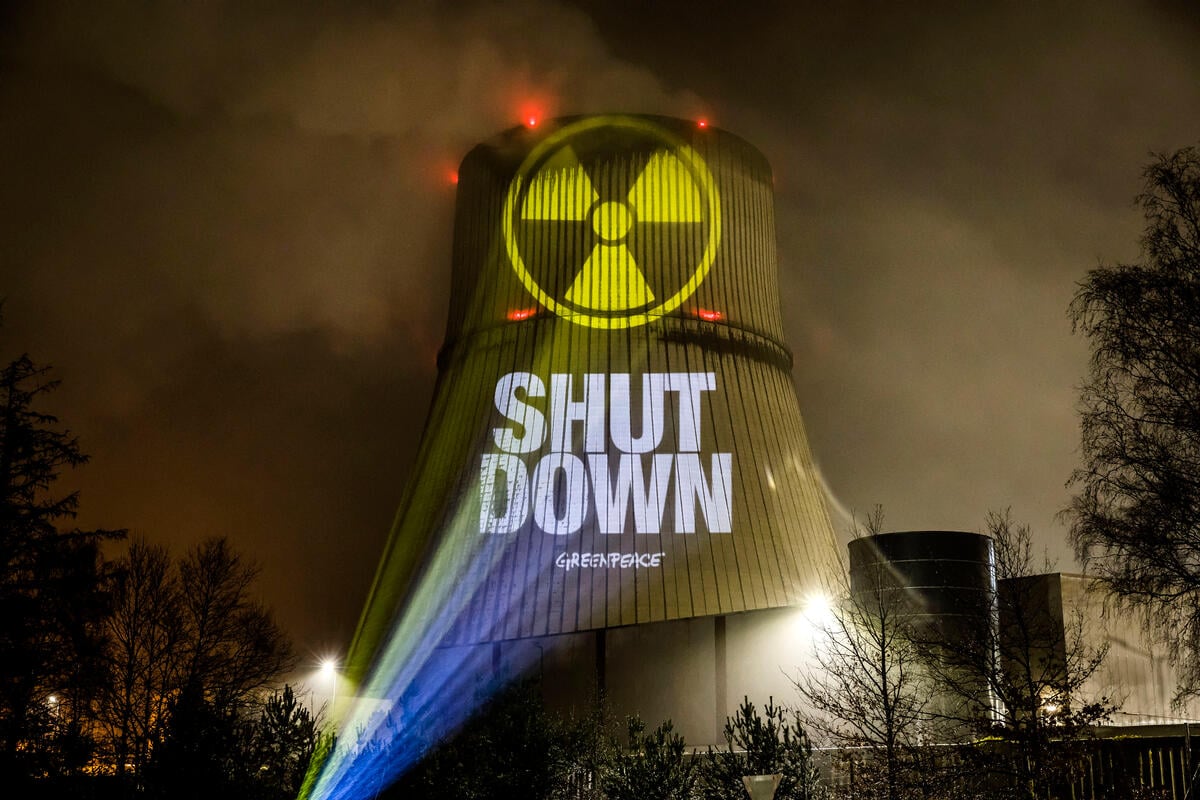

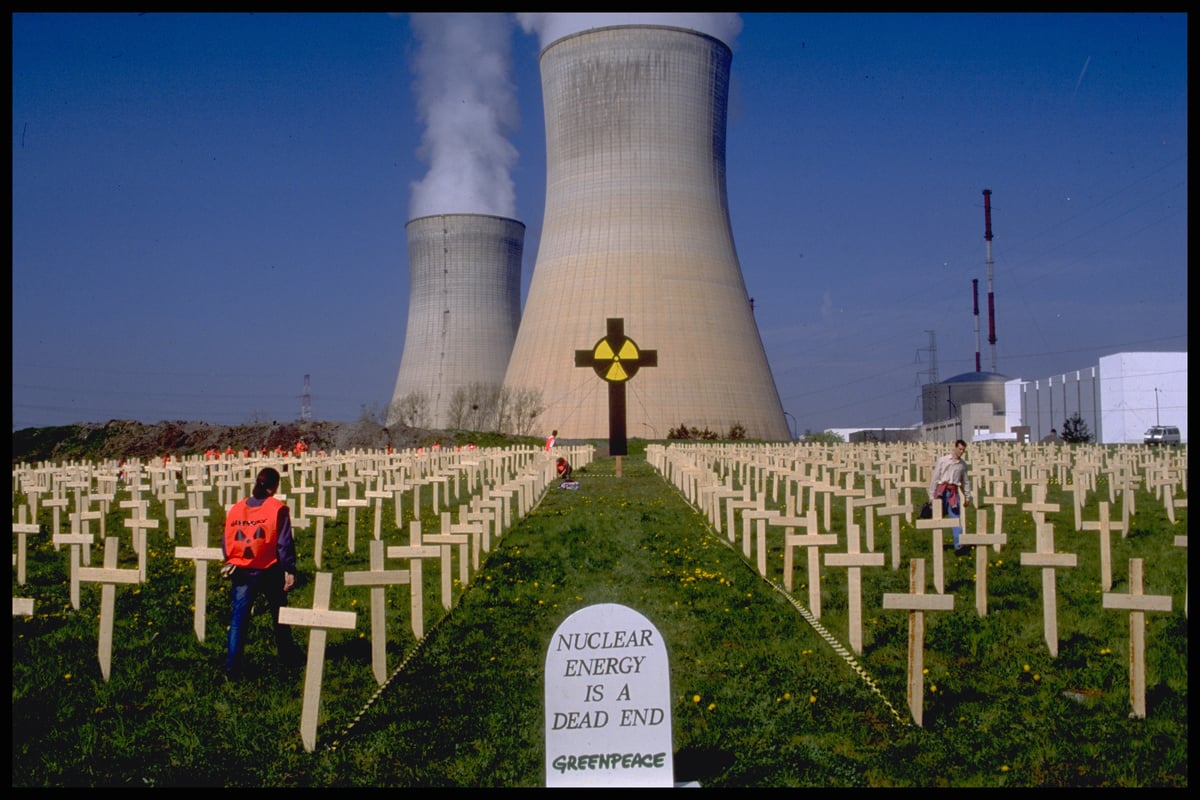

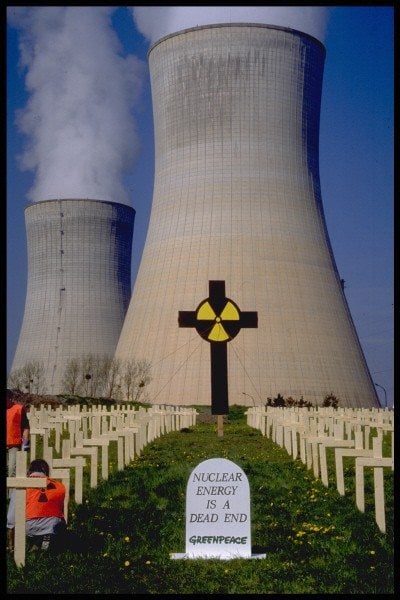

Greenpeace got its start protesting nuclear weapons testing back in 1971. We’ve been fighting against nuclear weapons and nuclear power ever since.

The history

High profile disasters in Chernobyl, Ukraine in 1986 and Fukushima, Japan in 2011 have raised public awareness of the dangers of nuclear power. Consequently, zeal for nuclear energy has fizzled. The catastrophic risks of nuclear energy — like the meltdowns of nuclear reactors in Japan or Ukraine — far outweigh the potential benefits.

New nuclear plants are more expensive and take longer to build than renewable energy sources like wind or solar. If we are to avoid the most damaging impacts of climate change, we need solutions that are fast and affordable. Nuclear power is neither.

We can do better than trading off one disaster for another. The nuclear age is over and the age of renewables has begun.

The dangers of nuclear energy

Nuclear reactors are inherently unsafe. Meltdowns like the ones in Fukushima or Chernobyl released enormous amounts of radiation into the surrounding communities, forcing hundreds of thousands of people to evacuate. Many of them may never come back. If the industry’s current track record is any indication, we can expect a major meltdown about once per decade. As a result, millions of people who live near reactors are at risk.

The possibility of a catastrophic accident at a U.S. nuclear plant can not be dismissed.

The aftermath of nuclear energy

Nuclear power plants typically have a design life of 40-60 years, whereas it might be more than 100 years after plant closure before decommissioning is completed. After a cooling-off period that could be as long as 50 or more years, nuclear reactors and uranium enrichment facilities must be decommissioned. All waste must be reprocessed or stored, structures decontaminated, and the land, air and water around the site remediated.

There is still no safe, reliable solution for dealing with the radioactive waste produced by nuclear plants.

Beyond the risks associated with nuclear power and radioactive waste, the threat of nuclear weapons looms large. The spread of nuclear technology and nuclear weapons is a threat for national security and the safety of the entire planet.

The true cost of nuclear energy

Nuclear energy isn’t just bad for the environment, it’s bad for our economy.

Public opposition over safety concerns around nuclear power necessitate high levels of regulation. From a risk perspective, this means that projects may be subject to delays and cost overruns as safety regulations are subject to changing and more stringent regulatory requirements.

Nuclear power plants are expensive to build, prompting Wall Street to call new nuclear a “bet the farm” risk.

This is even before taking into account the astounding cleanup and health costs caused by radioactive waste pollution and nuclear meltdowns. Cleaning up Fukushima, if ever possible, will cost at least $100 billion and could be more than double that.

Why invest money in a dangerous, unsustainable form of energy when we can have clean, renewable energy for less?

Nuclear energy is diverting attention and investment from the sustainable energy solutions we need. It’s time to stop building new nuclear facilities, phase out the ones that exist, and focus on clean energy for the future.

-

New Analysis of Five Major U.S. LNG Export Projects Finds Every One Fails the “Climate Test”

The new analysis shows that U.S. LNG export projects displace renewable energy and drive up emissions – making them incompatible with a livable climate

-

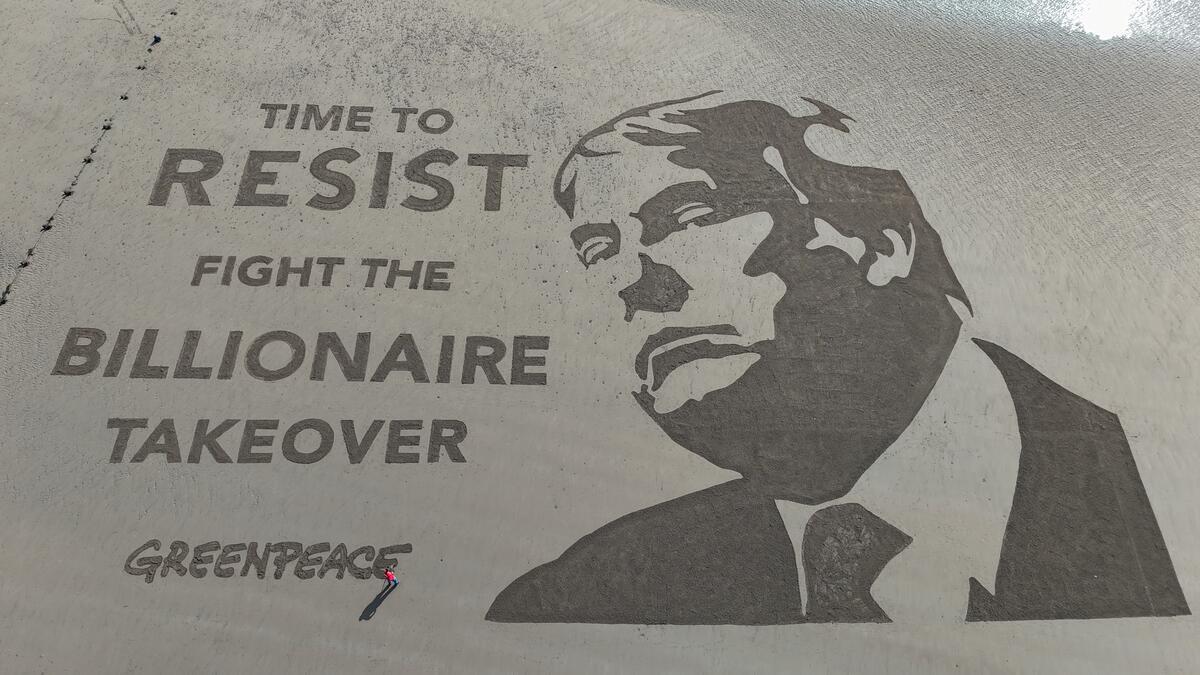

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

Nuclear Near Misses: A Decade of Accident Precursors at U.S. Nuclear Plants

Greenpeace has documented 166 near misses or accident precursors at U.S. nuclear power plants. Sixty one events and more than one hundred conditions were identified by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory…

-

Japan’s Nuclear Crisis

In the face of the continuing disaster, even Japanese Prime Minister Abe appears to be revising his position of 2013 that the situation at Fukushima is under control. The INES 7…

-

Fukushima Impact

The catastrophic nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, which began on 11 March 2011, not only crippled four of the reactors at the site, but also vividly…

-

Two Years after Fukushima, Duke Energy still making risky nuclear bets

Read More: Duke Energy’s risky nuclear bets

-

Chernobyl field findings – 25 years later

In March 2011, a Greenpeace research team visited several places in Rivnenska and Zhytomyrska Oblast, Ukraine, to collect samples of food products produced in those areas and which comprise a…

-

![Quit Nuclear Power – Invest in the Energy [R]evolution](https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-usa-stateless/2024/11/3e250054-gp1sx16j.jpg)

Quit Nuclear Power – Invest in the Energy [R]evolution

These goals are both possible to achieve at the same time.

-

Nuclear Reactor Hazards, Ongoing Dangers of Operating Nuclear

A comprehensive assessment of the hazards of operational reactors, new ‘evolutionary’ designs and future reactor concepts and the risks associated with the management of spent nuclear fuel, this report describes…

-

Nuclear Power: a dangerous waste of time

The nuclear power industry is attempting to exploit the climate crisis by aggressively promoting nuclear technology as a “low-carbon” means of generating electricity. Nuclear power claims to be safe, cost-effective,…