Protecting forests

Ending deforestation is our best chance to conserve wildlife while defending the rights of forest communities. It is also one of the quickest, most cost effective ways to slow the climate crisis.

Forests are our life support system

We are fighting to protect forests around the globe from destruction—and set them on a path to restoration. Working together with Indigenous Peoples, allies, and supporters like you, we’re calling out the industries and companies destroying our forests, and the governments who have failed to protect them.

Forests help stabilize the climate, sustain a diversity of life, and provide economic opportunity. They are vital to the livelihoods of many Indigenous Peoples and rural communities. Yet, forests and other critical ecosystems are being wiped out and converted to croplands, pasture, and plantations. Existing laws in many countries around the world remain deeply inadequate to protect these forests. The few regulations in place are too often poorly enforced.

From the Amazon to Canada to Indonesia, half of our global forests have already been lost forever to unsustainable industrial practices. The need to protect the world’s remaining forests is more urgent than ever. The loss of these vital ecosystems is displacing communities, threatening the habitats of rare and endangered species, and spewing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The 2024 The State of the World’s Forests report and the Global Biodiversity Outlook 5 report continue to underlined the urgency of saving forests in order to curb the extinction crisis and fight the climate crisis. To avoid further catastrophic consequences, we urgently need to protect and restore forests and recognize the rights of Indigenous Peoples everywhere.

Agribusiness drives deforestation

The food system is broken. Industrial agriculture contributes to 80% of deforestation across the globe, posing a threat to communities and the planet. Greedy companies are literally setting tropical forests on fire to clear land and expand their cattle grazing and feed, fueling the climate crisis.

Learn more about…

Brazil and the Amazon forest

Indonesian forests and palm oil

-

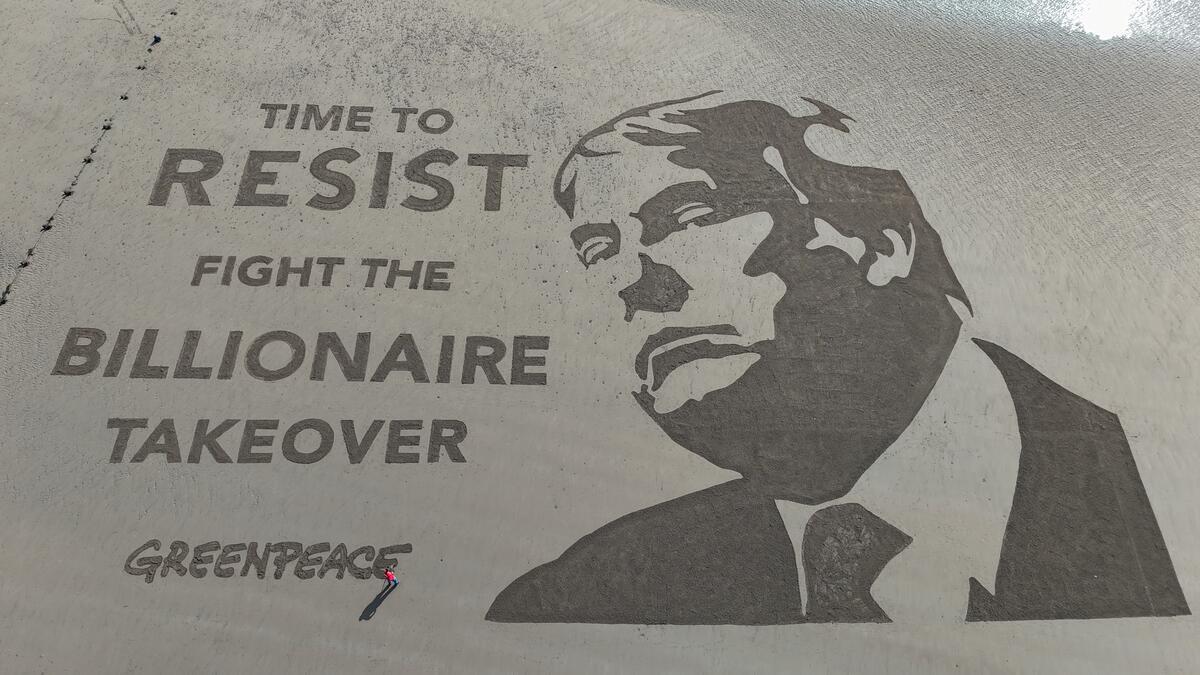

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

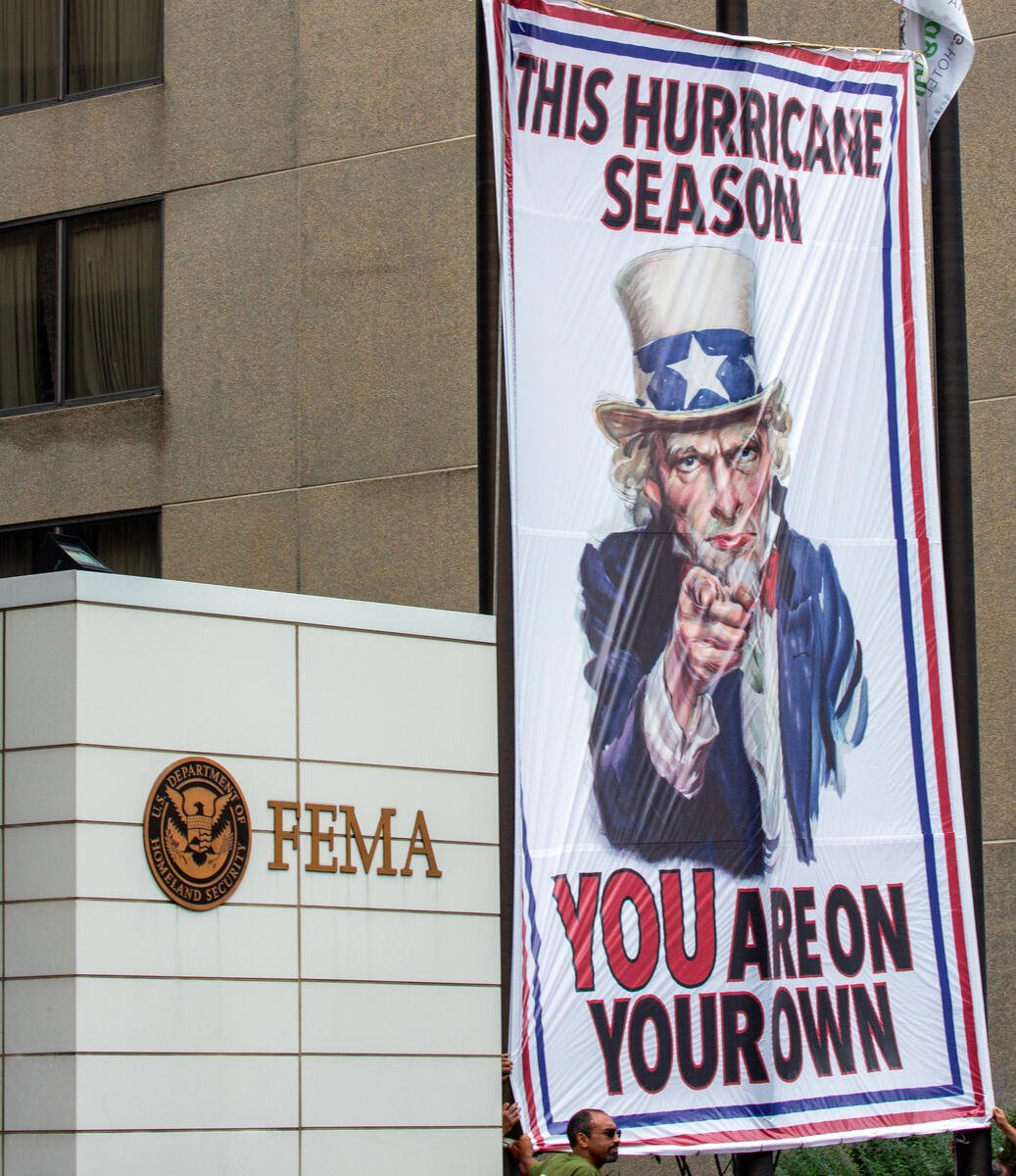

This hurricane season Greenpeace USA helps deliver Uncle Sam’s disturbing message to America

Greenpeace USA deployed a banner at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) headquarters to assist in making Uncle Sam’s message to the country crystal clear: this hurricane season, you are…

-

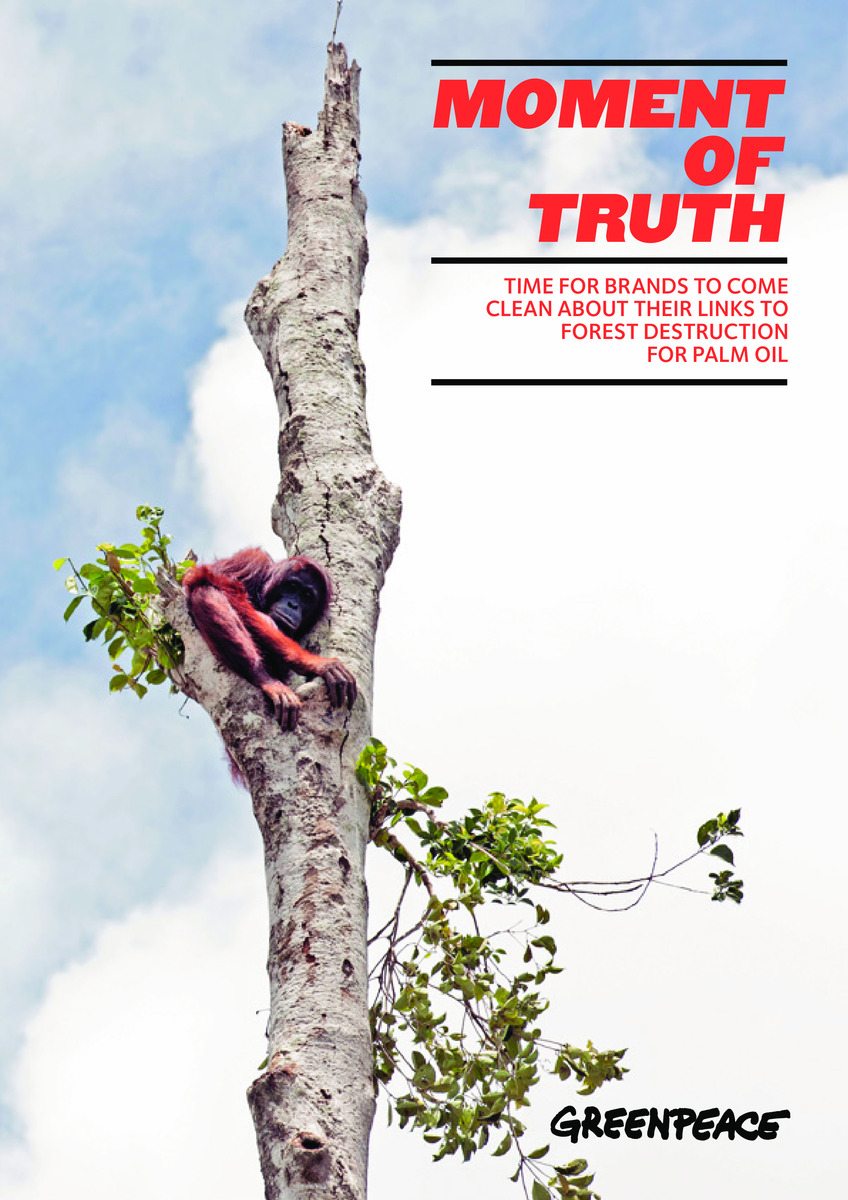

Moment of Truth: Time for Brands to Come Clean About Their Links to Forest Destruction for Palm Oil

It has been close to a decade since consumer brands pledged to eliminate deforestation from palm oil and other key commodities by 2020. Despite these commitments, there is growing evidence…

-

A Deadly Trade-off: IOI’s Palm Oil Supply and Its Human and Environmental Costs

This Greenpeace International investigative report looks at the Malaysian palm oil company IOI Group and its downstream subsidiary in Europe and North America, IOI Loders Croklaan. Despite policies to ensure…

-

Cutting Deforestation Out of Palm Oil – Company Scorecard

Click here to download the full report: “Cutting Deforestation Out of Palm Oil.” In 2015, Indonesia was wracked by the worst forest fires for almost twenty years. The disaster, the…

-

Licence to Launder

The oil palm plantation being developed by Herakles Farms in the southwest region of Cameroon – an area of great biodiversity surrounded by five protected areas – illustrates what happens when irresponsible companies are not held accountable to local laws and processes. The companies activities pose a serious threat to forested areas and the communities…

-

Logging: The Amazon’s Silent Crisis

Governance in the timber sector in the Brazilian Amazon is weak and open to exploitation, allowing criminals launder illegal timber as legal with official documentation. It is estimated that in…

-

Herakles Exposed

The report details a series of 9 misstatements, lies, or inaccuracies found in communications from Herakles Farms around their palm oil project in Cameroon.

-

Palm Oil’s New Frontier

When it is done well and is properly managed, palm oil production can be of potential benefit to the populations of developing countries, providing sustainable livelihoods. On the other hand,…

-

Junking the Jungle

Greenpeace research has tracked a number of these products back to Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), a company that continues to rely on rainforest clearance in Indonesia. By purchasing paper…

-

Driving Destruction in the Amazon

Two years of Greenpeace investigations, summarized in this report, reveal that end users including major global car manufacturers – indirectly or directly source pig iron whose production is fueled by…

-

The Ramin paper Trail

A year-long investigation by Greenpeace International demonstrates that Asia Pulp & Paper (APP) is breaking Indonesian law, driving Sumatran tigers and ramin trees closer to extinction, and undermining CITES –…

-

Protection Money

I am confident that we can reach this goal [of GHG emissions reduction targets], while also ensuring sustainable and equitable economic growth for our people.