All articles

-

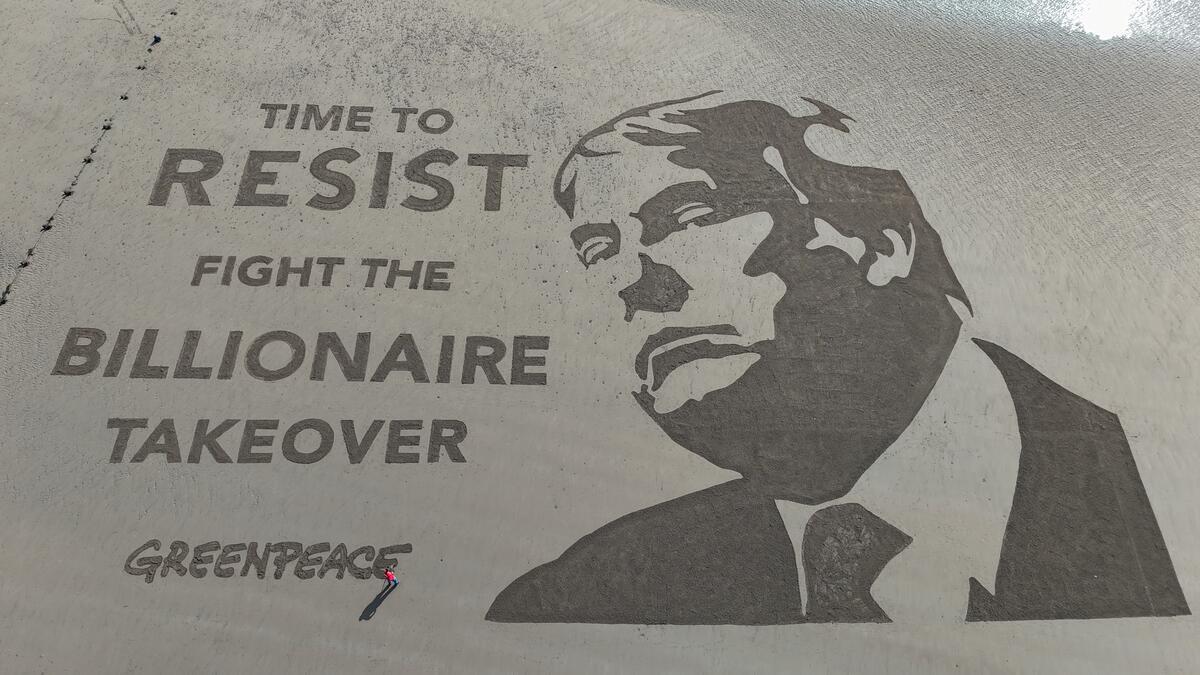

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

Greenpeace USA responds to Energy Transfer Q1 earnings call announcement

In response to Energy Transfer announcing $4.1B in 2025 Q1 profits, Sushma Raman, Greenpeace USA Interim Executive Director, issued the following statement:

-

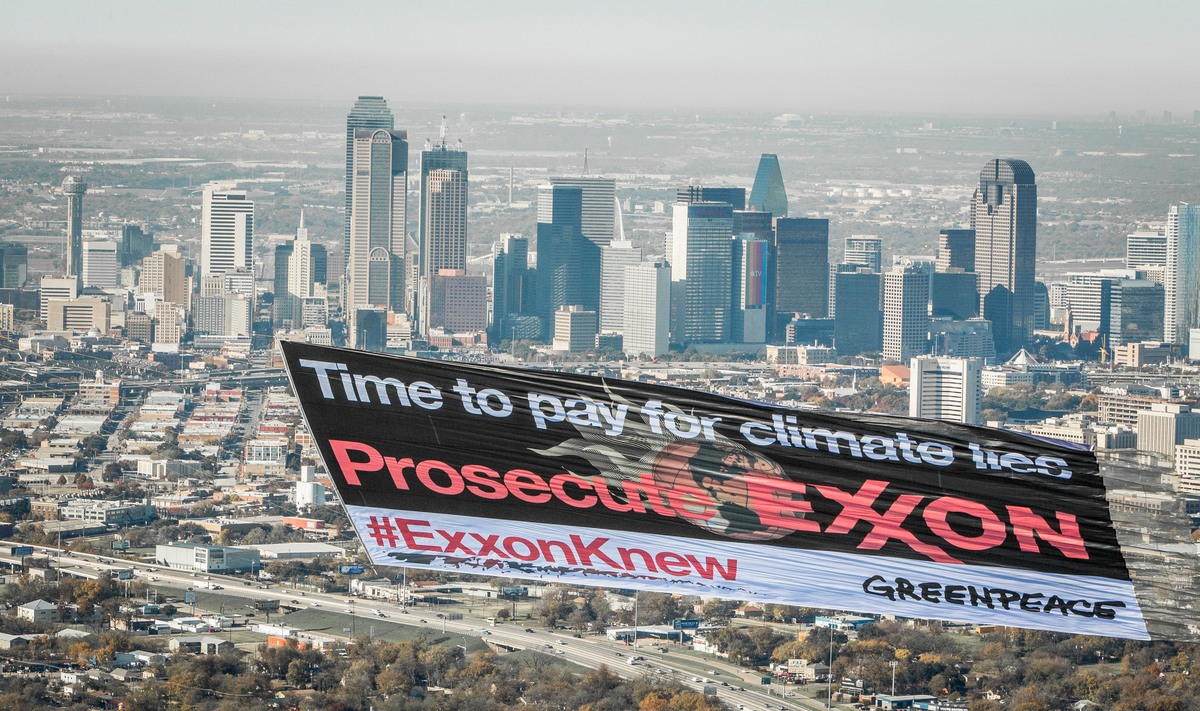

Inside the hack-for-hire scandal: ongoing saga to uncover potential Exxon-linked cyberattacks intended to derail climate accountability

New details on the targets and motives behind the global hacking scandal emerge amid an escalating international legal battle.

-

Trump vs. Plastic Pollution

In his first month back in the Oval Office, Trump made moves that sent shockwaves in the world of plastic pollution. First, there was the announcement of a 25% tariff…

-

Energy Transfer lawsuit verdict

The jury has officially reached a verdict in our trial against Big Oil company Energy Transfer’s meritless lawsuit. We’re going to appeal.

-

Greenpeace USA demands Congress defend the Constitution

WASHINGTON, D.C. (March 18, 2025) – In response to the unlawful detainment of student activist and U.S. legal permanent resident Mahmoud Khalil, Greenpeace USA has signed on to a letter…

-

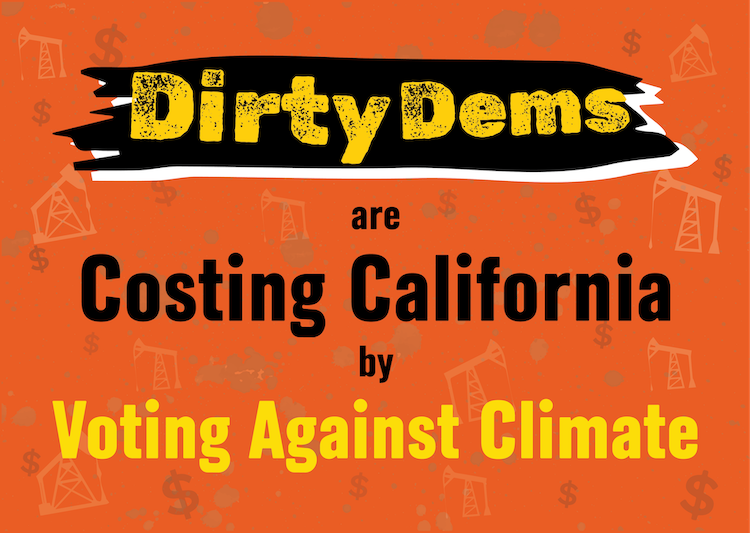

California’s dirty democrats exposed!

New bills are circulating framed as 'public safety' measures, but there is no evidence that they improve energy reliability or make communities safer.

-

The BOWSER Act and federal highjacking of local governance

BOWSER Act is a racist attacks on DC home rule & another attempt by right-wing lawmakers to strip Black/Brown communities of their rights. DC residents deserve full autonomy & representation. Congress must reject this assault on democracy.

-

Fossil fuel anti-protest bills in Montana, Virginia, and Illinois threaten climate activism

New bills are circulating framed as 'public safety' measures, but there is no evidence that they improve energy reliability or make communities safer.

-

Energy Transfer thinks they can silence us

Big Oil company Energy Transfer is trying to silence Greenpeace with a $300 million lawsuit. They've ignited a reinvigorated global movement.