Ending the climate crisis

We’re in a climate emergency and the oil, gas, and coal industry is to blame.

Our climate is in crisis

Scientists are shouting an urgent warning: We have little more than a decade to take bold, ambitious action to transition our economy off of coal, oil, and gas, and onto safe and green renewable energy. Shifting to cleaner, locally-run energy will not only slow the tide of the climate crisis, it’ll create millions of new jobs that sustain families while protecting community health.

For the last decade, many elected leaders and corporations have claimed to care about our future, but have done little more than say they believe climate change is real. Those talking points don’t cut it anymore.

It’s time to put people above the fossil fuel industry and truly act on climate.

The time is now

With enough pressure, we can push leaders to start responsibly phasing out coal, oil, and gas while prioritizing support for disadvantaged communities and workers most affected by moving to a safer, more caring economy. Together we can also make sure that communities impacted by extreme climate impacts will have everything they need to recover in a way that supports sustainable and livable communities, and holds fossil fuel executives accountable. True climate action also means that giant multinational corporations like Amazon need to invest in locally-run renewable energy to power their operations instead of dirty, dangerous energy production.

We deserve a world where everyone can thrive without worrying about their health, finances, or pollution.

Learn more about…

California climate emergency

Extreme weather

Fossil fuel phase-out

The Arctic

-

New Analysis of Five Major U.S. LNG Export Projects Finds Every One Fails the “Climate Test”

The new analysis shows that U.S. LNG export projects displace renewable energy and drive up emissions – making them incompatible with a livable climate

-

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

Permit To kill: Potential health and economic impacts from U.S. LNG export terminal permitted emissions

Research from Sierra Club and Greenpeace USA shows that permitted emissions from LNG terminals are associated with major public health costs.

-

What Biden’s LNG Pause Does and Doesn’t Do

Today the Biden-Harris Administration announced a “pause” on new export approvals for liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects, while the Department of Energy (DOE) reviews its LNG export policy. This is…

-

LNG Tanker Tracker

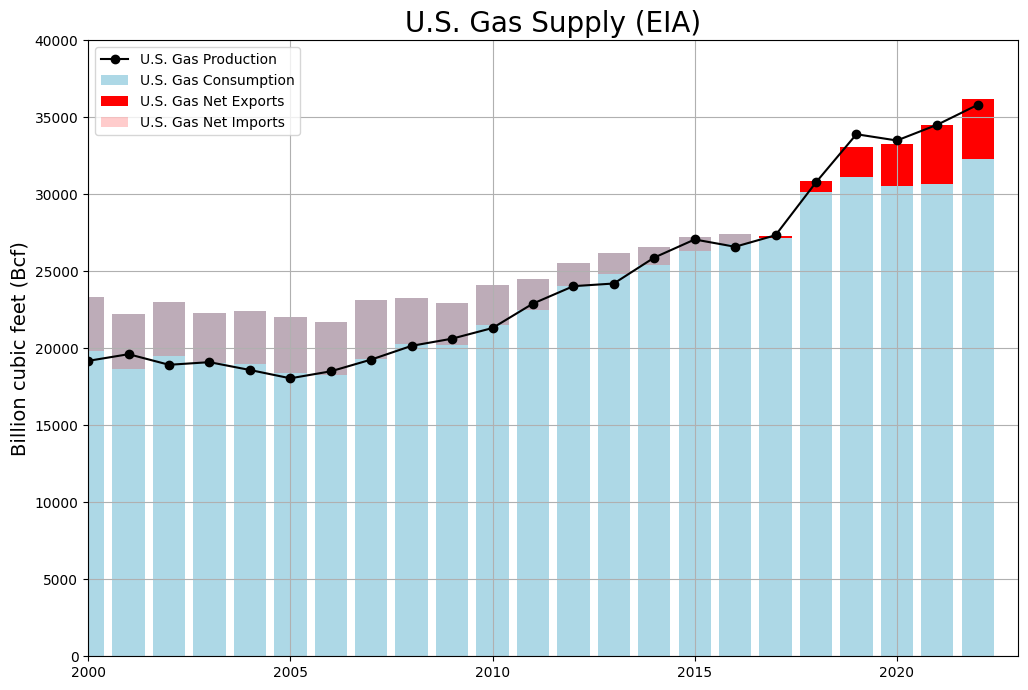

The U.S. recently became the world’s leading exporter of liquified natural gas (LNG). Much of that is exported via the Gulf Coast from facilities in Texas and Louisiana. Greenpeace USA…

-

Gulf Coast Terminal Build Out

Methane gas is converted into Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and then loaded onto tankers at large, complex export terminals. The scale of LNG exports is limited by the capacity of…

-

What are LNG Exports?

Methane or fossil gas (usually called “natural” gas in the U.S.) is a fossil fuel that is used to generate electrical power, heat buildings, and power heavy industry. Thanks to…

-

Liquefied Natural Gas Exports 101

In recent years, the United States has become the world’s largest oil and gas driller, and an increasing amount of fossil gas production is being directly exported to other countries…

-

Too Fast For Gas: Problems at Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass Should Not Be Overlooked

Last month, Venture Global told regulators and customers that issues with the Calcasieu Pass LNG facility will delay the start of commercial operations. They described the issues as “failures in…

-

Madness Is The Method: How Cheniere is Greenwashing its LNG With New Cargo Emissions Tags

Full Report Download English Full Report Follow the story: The initial Life-Cycle Assessment paper Our letter to the editor commenting on their paper Their reply to…