Global Plastics Treaty

Plastic is harmful to human health, perpetuates social injustice, destroys our biodiversity, and fuels the climate crisis. We demand that governments commit to a strong Global Plastics Treaty that will cut plastic production by at least 75% by 2040 to stay below 1.5 C and end single-use plastic.

What is the Global Plastics Treaty?

Governments around the world are negotiating a Global Plastics Treaty, an agreement that could alleviate the triple planetary crisis of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss fueled by rampant plastic production. Plastic pollution not only poses a severe threat to human health at an unimaginable scale, but it also worsens racial, gender, and economic inequality globally.

In March 2022, at the United Nations Environmental Assembly (UNEA), governments officially agreed to begin negotiations for a global, legally binding plastics treaty that addresses the whole lifecycle of plastics.

Negotiations for the Global Plastics Treaty are currently underway, with the initial goal of finalizing the agreement by the end of 2024 — however, a deal has not been finalized yet. Delegates from over 100 countries, representing billions of people, rejected a toothless deal that would have accomplished nothing.

We now have one more chance to make a strong plastics treaty a reality at the next 2025 UN meeting. The treaty has immense potential to set the world on a path toward a plastic-free future, but we need to make sure that it delivers on its promises.

Join the movement

We have a chance to end the plastic crisis by pushing for a strong and ambitious Global Plastics Treaty that cuts plastic production and ends single-use plastic. We know that the petrochemical industry, corporations and some governments will try to weaken the ambition of the Global Plastics Treaty, and here is where the battle truly begins.

Greenpeace has been present at every negotiation, representing you – an unstoppable global movement calling on world leaders to deliver an ambitious Global Plastics Treaty that will turn off the plastics tap. We will continue to show up at each negotiation until we end the age of plastic.

Why do we need a Global Plastics Treaty?

Plastic pollution is one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time, with its impacts worsening every day. From extraction as fossil fuel to disposal, plastic pollutes at every stage of its lifecycle. We need a strong Global Plastics Treaty that meets the scale of this crisis and addresses plastic pollution at the source.

Governments must commit to negotiating a strong plastics treaty that protects our climate by keeping oil and gas in the ground and drastically cutting plastic production. Without action, plastic production is currently set to triple by 2050, potentially consuming up to one-fifth of the world’s remaining carbon budget and undermining efforts to address the climate crisis.

We urgently need governments around the world to implement national policies that push big brands and Big Oil to phase out single-use plastic, invest in reuse systems, and negotiate a strong Global Plastics Treaty that will cut total plastic production and prevent the most dire impacts of a rapidly warming planet.

A strong and ambitious plastics treaty is our best chance for a cleaner, safer future — for our health, our communities, our climate, and our planet.

Greenpeace’s demands:

- The Global Plastics Treaty must cut total plastic production by at least 75% by 2040 to ensure that we are staying below 1.5° C for our climate and to protect our health, our rights, our communities and our environment.

- As we head into the last round of negotiations, blocker countries continue to oppose meaningful provisions. We need high-ambition countries to show more courage and fight for ambition to reach a treaty that will cut plastic production and end single-use plastic, starting with the worst offending items like plastic sachets.

- The Global Plastics Treaty must be built upon a foundation of human rights. It must reduce inequalities, end waste colonialism, prioritize human health, center justice, and ensure dignity for all. An effective treaty must protect biodiversity, safeguard our climate, and ensure a just transition to a reuse-based economy.

Learn more about…

The myth of recycling

Plastics & health

-

New Analysis of Five Major U.S. LNG Export Projects Finds Every One Fails the “Climate Test”

The new analysis shows that U.S. LNG export projects displace renewable energy and drive up emissions – making them incompatible with a livable climate

-

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

Forever Toxic: The science on health threats from plastic recycling

Without dramatically reducing plastic production, it will be impossible to end plastic pollution and eliminate the health threats from chemicals in plastics.

-

Circular Claims Fall Flat Again

A recent Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report projects that global plastic use and waste will nearly triple by 2060 with a meager increase in plastic recycling, resulting in a doubling of global plastic pollution. The United States Department of Energy (U.S. DOE) estimated that the volume of plastic waste in the U.S.…

-

The Climate Emergency Unpacked: How Consumer Goods Companies are Fueling Big Oil’s Plastic Expansion

As the climate crisis intensifies, there is growing worldwide acceptance of the need to slash greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the burning of fossil fuels to limit global heating to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels

-

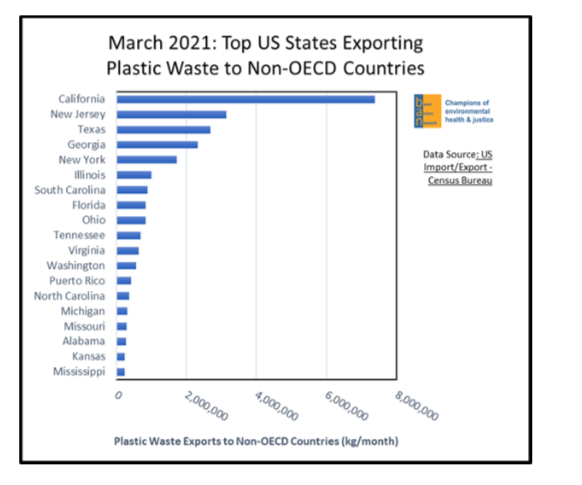

Acceptance of Unrecyclable Plastic Products and California’s Continued Exports of Plastic Waste Exports to Non-OECD Countries

To Statewide Commission on Recycling Markets and Curbside Recycling SUBJECT: Acceptance of Unrecyclable Plastic Products and California’s Continued Exports of Plastic Waste Exports to Non-OECD Countries The co-signers of this…

-

Deception by the Numbers: Claims about Chemical Recycling Don’t Hold Up to Scrutiny

Despite decades of deceptive industry marketing, we know we can’t recycle our way out of the plastic pollution crisis. But the companies making and selling plastic—and their trade association surrogate,…

-

Reusables are doable

It is time to stop treating people and the planet as disposable. To save our climate and ensure healthy communities for everyone, we must end our reliance on cheap throwaway plastics.

-

The Making of an Echo Chamber: How the plastic industry exploited anxiety about COVID-19 to attack reusable bags

In a new research brief, Greenpeace USA details the ways the plastics industry is exploiting people’s fears around COVID-19. Through front groups, corporate-funded research, and misrepresentation of scientific studies, the…

-

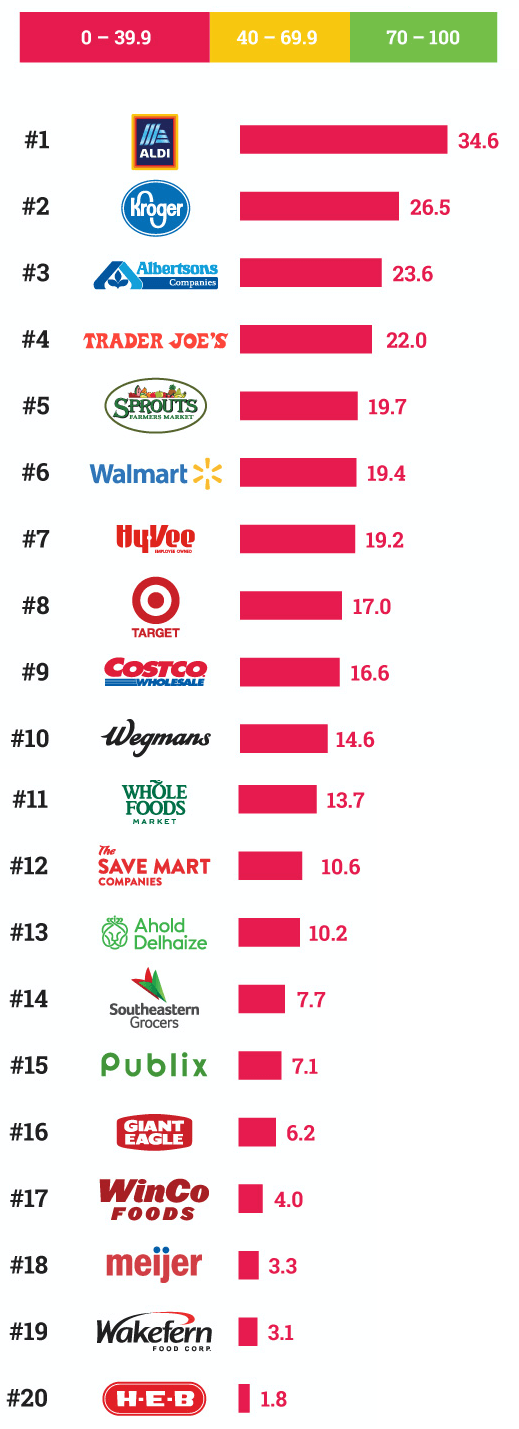

Report: Circular Claims Fall Flat

In a new Greenpeace report, a comprehensive survey of plastic product waste collection, sortation and reprocessing in the United States (U.S.) was performed to determine the legitimacy of “recyclable” claims…

-

Report: The Smart Supermarket

A new Greenpeace USA report walks readers through The Smart Supermarket, a hypothetical store that has moved beyond single-use plastics and packaging. As retailers grapple with how to transition away…

-

Throwing Away the Future: How Companies Still Have It Wrong on Plastic Pollution “Solutions”

A Greenpeace USA report released today, Throwing Away the Future: How Companies Still Have It Wrong on Plastic Pollution “Solutions,” warns consumers to be skeptical of the so-called solutions announced…

-

Greenpeace Report: Packaging Away the Planet

The entire lifecycle of plastic production, use, and disposal is destroying our communities and environment.