Fighting plastic pollution

For centuries, people have assumed that our vast ocean was limitless and immune to human impacts. It’s only recently that scientists have come to understand the devastating effects plastics have already had on the seas.

What is the plastic pollution crisis?

The flow of plastics into our environment has reached crisis proportions, and the evidence is most clearly on display in our oceans. It is estimated that up to 12 million metric tons of plastic enter our ocean each year.

However, plastic is not just an ocean and waste problem, it is also a climate, health and social justice problem. 99% of plastic is made from fossil fuels, like fracked gas and oil, and it contributes to climate change throughout its life-cycle.

Global demand for plastics

As global demand for oil declines, the fossil fuel industry is turning to plastics to stay afloat. Big plastic-polluting corporations like Coca-Cola, Nestlé and PepsiCo are driving this growth and their failure to end their reliance on single-use plastics and invest in reuse and refill is contributing to fossil fuel production expansion, and laying the groundwork for a devastating boom in single-use plastics. And if industry has its way, plastic production could double by 2030.

The fossil fuel industry’s increased reliance on plastics will be just as harmful for people and the planet. Beyond continuing to drive the climate crisis, petrochemical and plastic production have deadly health and environmental impacts and a long history of environmental racism, from the U.S. Gulf Coast’s “Cancer Alley” where the plastic industry is poisoning Black, Brown and frontline communities to China’s Cancer Village in the Global South.

How did the plastic pollution crisis happen?

In the 1970s, the petrochemical and fossil fuel industry, alongside consumer goods giants, spent millions of dollars on ads to push the myth of plastic recycling to trick customers into believing that recycling was a real solution for the explosion of plastic packaging.

We now know that over 90% of plastic is not recycled, and that rhetoric was an industry smokescreen in order to pump out more and more plastics for profit. Recycling is not — and has never been — a real solution for plastics, and our environment, oceans, and communities are paying the devastating price for the crisis.

What can we do about plastic pollution?

As the makers of plastic — the oil and gas industry — double down on plastics as the next frontier for future petrochemical production, we must fight back to expose the fossil fuel industry hiding behind plastics. And demand action from the biggest plastic polluting corporations fueling the plastic crisis by continuing to cut off a major lifeline of the fossil fuel industry: single-use plastics.

Right now, we also have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to match the scale of this crisis —A Global Plastics Treaty.

At the United Nations Environmental Assembly in March 2022, governments officially adopted a mandate opening negotiations for a global, legally-binding plastics treaty to address the whole lifecycle of plastics.

The negotiations for the Global Plastics Treaty have started, with the initial goal of completing the process by the end of 2024 — however, a deal has not been finalized yet. Delegates from over 100 countries, representing billions of people, rejected a toothless deal that would have accomplished nothing.

The future treaty has a huge potential to put the world on a path towards a plastic-free future but it will be up to us to make sure that it delivers on its promises. The fight for a plastic-free future continues!

A global movement

We demand that world leaders champion an ambitious and strong global plastics treaty that will limit plastic production and use. A strong global plastics treaty will keep oil and gas used to produce plastic in the ground and stop big polluters with their relentless plastic production. A strong plastics treaty will deliver a cleaner, safer planet for us and for future generations

And with an unstoppable global movement of millions of people around the world, we can achieve an ambitious Global Plastics Treaty that will turn off the plastics tap and finally, end the age of plastic – for our health, our communities, climate, and the planet.

Learn more about…

The Global Plastics Treaty

Plastics & health

The myth of recycling

-

New Analysis of Five Major U.S. LNG Export Projects Finds Every One Fails the “Climate Test”

The new analysis shows that U.S. LNG export projects displace renewable energy and drive up emissions – making them incompatible with a livable climate

-

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

Forever Toxic: The science on health threats from plastic recycling

Without dramatically reducing plastic production, it will be impossible to end plastic pollution and eliminate the health threats from chemicals in plastics.

-

Circular Claims Fall Flat Again

A recent Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report projects that global plastic use and waste will nearly triple by 2060 with a meager increase in plastic recycling, resulting in a doubling of global plastic pollution. The United States Department of Energy (U.S. DOE) estimated that the volume of plastic waste in the U.S.…

-

The Climate Emergency Unpacked: How Consumer Goods Companies are Fueling Big Oil’s Plastic Expansion

As the climate crisis intensifies, there is growing worldwide acceptance of the need to slash greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the burning of fossil fuels to limit global heating to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels

-

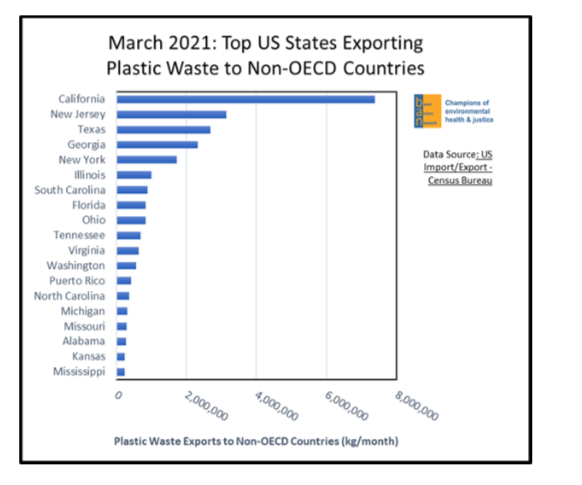

Acceptance of Unrecyclable Plastic Products and California’s Continued Exports of Plastic Waste Exports to Non-OECD Countries

To Statewide Commission on Recycling Markets and Curbside Recycling SUBJECT: Acceptance of Unrecyclable Plastic Products and California’s Continued Exports of Plastic Waste Exports to Non-OECD Countries The co-signers of this…

-

Deception by the Numbers: Claims about Chemical Recycling Don’t Hold Up to Scrutiny

Despite decades of deceptive industry marketing, we know we can’t recycle our way out of the plastic pollution crisis. But the companies making and selling plastic—and their trade association surrogate,…

-

Reusables are doable

It is time to stop treating people and the planet as disposable. To save our climate and ensure healthy communities for everyone, we must end our reliance on cheap throwaway plastics.

-

The Making of an Echo Chamber: How the plastic industry exploited anxiety about COVID-19 to attack reusable bags

In a new research brief, Greenpeace USA details the ways the plastics industry is exploiting people’s fears around COVID-19. Through front groups, corporate-funded research, and misrepresentation of scientific studies, the…

-

Report: Circular Claims Fall Flat

In a new Greenpeace report, a comprehensive survey of plastic product waste collection, sortation and reprocessing in the United States (U.S.) was performed to determine the legitimacy of “recyclable” claims…