Protect the oceans

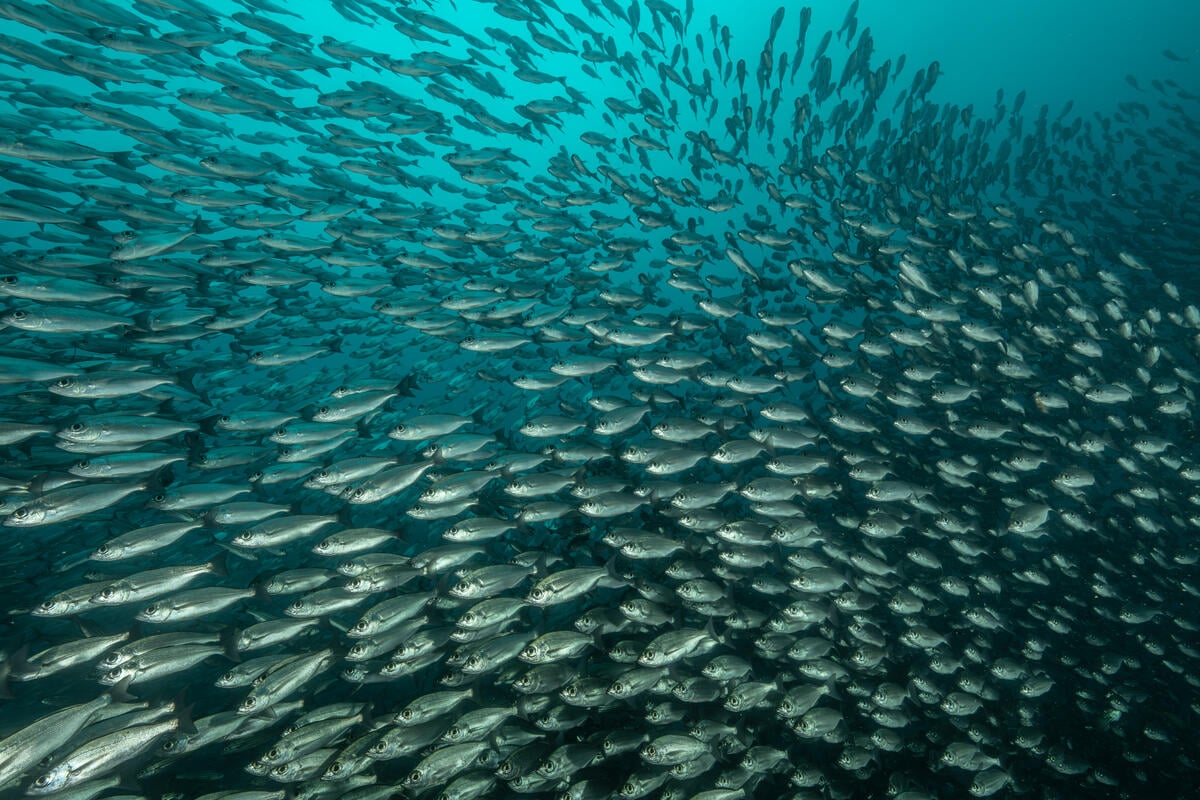

For centuries, people have assumed that our vast ocean was limitless and immune to human impacts. It’s only recently that scientists have come to understand the devastating effects we’ve already had on the seas.

The oceans are in more trouble than ever before

Right now it is estimated that up to 12 million metric tons of plastic—everything from plastic bottles and bags to microbeads—end up in the oceans each year. That’s a truckload of trash every minute.

Traveling on ocean currents, this plastic is now turning up in every corner of our planet, from Florida beaches to uninhabited Pacific islands. It is even being found in the deepest part of the ocean and trapped in Arctic ice.

The oceans are slowly turning into a plastic soup, and the effects on ocean life are devastating. Plastic pieces of all sizes choke and clog the stomachs of creatures who mistake it for food, from tiny zooplankton to whales. Plastic is now entering every level of the ocean food chain and is even ending up in the seafood on our plates.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. That’s why we are campaigning to end the flow of single-use plastic into our oceans.

How we protect the oceans

We are calling on big corporations to act to reduce their plastic footprint—and stop producing plastic packaging that is designed to be used for just a few minutes before it ends up in landfills, incinerators and out polluting our environment for a lifetime.

We’re also working hard to address other serious threats facing our oceans. Unsustainable industrial fishing is destroying habitats and endangering countless species. The climate crisis and ocean acidification—both the result of our reliance on fossil fuels—are having more and more extreme impacts on ocean health. Today, overfishing and bycatch kills about 63 billion pounds of marine animals every year. Human activity is disrupting the balance of marine ecosystems across the globe. The impacts on humans are equally severe. Overfishing compromises food security and the livelihoods of fishing communities. Human trafficking and forced labor remain huge problems on many fishing fleets.

We’re also working to protect the oceans through a network of sanctuaries. Globally, less than 2 percent of the ocean is under protection. We’re campaigning to establish ocean sanctuaries in 30 percent of the world’s oceans by 2030.

These sanctuaries will preserve biodiversity, help endangered species recover, and give marine life a fighting chance to survive the rapid changes we are causing to the planet. Ocean sanctuaries can also help replenish fish populations decimated by overfishing. This would mean a more dependable food supply for the billions of people who get some of their protein from seafood.

Scientists say the wave of extinction facing the ocean in the coming century could be the worst since the dinosaur age. If we don’t change the way we do things, and fast, we are on track to cause irreversible damage to the ocean and the collapse of some of the most important food sources in the world.

If we work together, a world that respects our oceans, their inhabitants, and the people who depend on them is in our reach. We want a better future for our oceans and the people that depend on them. Learn more about our campaign to protect the oceans and ways you can get involved.

Learn more about…

Protecting workers & wildlife at sea

The Global Oceans Treaty

The threats facing our oceans get more urgent every day. The vast areas outside countries’ national waters are in the most danger, as they don’t have any proper protection, which leaves whales, turtles and dolphins at risk.

Scientists have a new rescue plan for our oceans: a global network of ocean sanctuaries that would put millions of square miles off limits to destructive industries. But to make that happen, world governments must ratify the Global Ocean Treaty at the United Nations in 2025. We need as many people as possible to show these decision-makers why ocean protection matters.

-

New Analysis of Five Major U.S. LNG Export Projects Finds Every One Fails the “Climate Test”

The new analysis shows that U.S. LNG export projects displace renewable energy and drive up emissions – making them incompatible with a livable climate

-

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

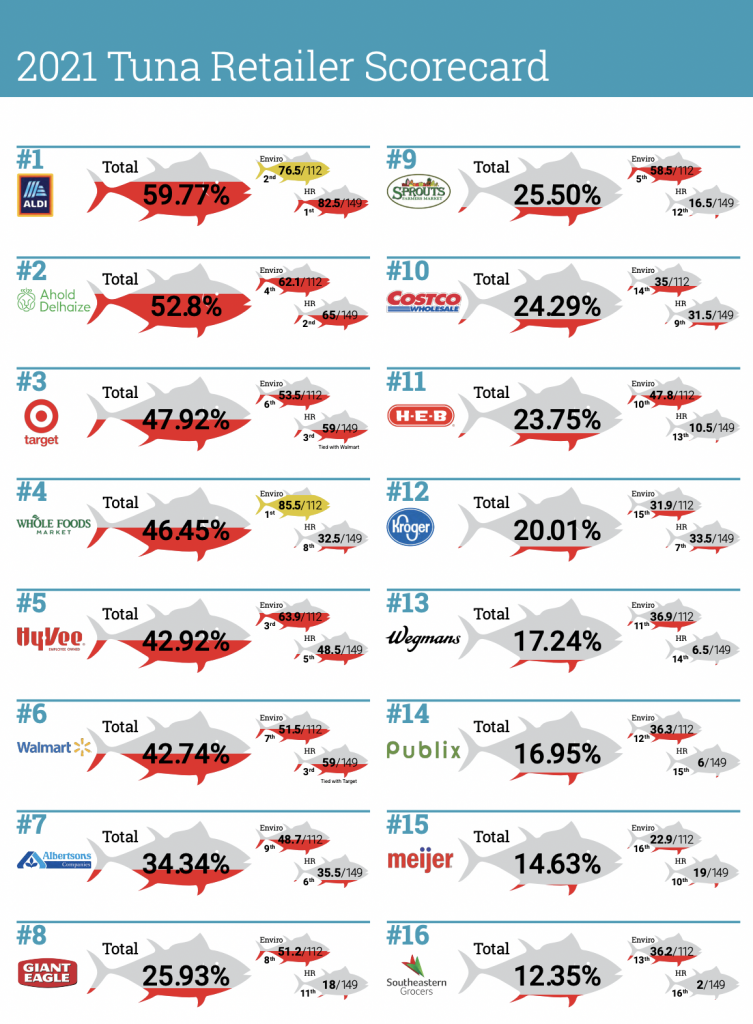

The high cost of cheap tuna: US supermarkets, sustainability, and human rights at sea (3rd edition)

In Greenpeace USA’s third scorecard measuring the human rights and sustainability practices of 16 major US supermarkets’ tuna supply chains, only two retailers achieved a passing score.

-

The High Cost of Cheap Tuna: US Supermarkets, Sustainability, and Human Rights at Sea

Published: 02-13-2023 Edition: 2nd Download: PDF A net bulging with tuna and bycatch on the Ecuadorean purse seiner ‘Ocean Lady’, which was spotted by Greenpeace in the vicinity of the northern Galapagos Islands while using fishing aggregating devices (FADs). Around 10% of the catch generated by purse seine FAD fisheries is unwanted bycatch and includes…

-

Fake My Catch: The Unreliable Traceability in our Tuna Cans

US seafood company Bumble Bee, one of the leading companies in the canned tuna market with nearly 90% consumer awareness levels, and its Taiwanese parent company Fong Chun Formosa Fishery Company (hereinafter referred to as FCF), one of the top three global tuna traders, play an important role in the global tuna industry, and thus…

-

2021 Tuna Retailer Scorecard: The High Cost of Cheap Tuna

When Greenpeace USA published the first edition of Carting Away the Oceans (CATO) in 2008, not a single company out of the 16 major US retailers ranked on seafood sustainability received a passing score. Most of the companies surveyed had hardly given a thought to sustainable seafood; many had weak or non-existent policies, and commonly…

-

Fact Sheet: The Illegal Fishing and Forced Labor Prevention Act

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, a top threat to ocean ecosystems and global food security, is inextricably linked to human rights abuses at sea. Workers on fishing vessels around…

-

High Stakes: The Impacts of Destructive Fishing

The Indian Ocean is a crucial ecosystem in the race to protect the high seas. From safeguarding marine biodiversity to promoting sustainable, socially responsible fishing, the changes needed to protect…

-

Comments Concerning the Ranking of Taiwan by the U.S. Department of State in the 2021 Trafficking in Persons Report

Publication Date: April 1, 2021 Author: GLJ-ILRF and Greenpeace on behalf of the Seafood Working Group This document contains the Seafood Working Group (SWG)’s comments concerning Taiwan’s ranking in the…

-

Fisheries Observers are Human Rights Defenders on the World’s Oceans

Fisheries observers are human rights defenders on the world’s oceans. These individuals work independently onboard commercial fishing vessels around the world to collect scientific data on the state of the…

-

Policy Briefing: Why the Department of Labor Must Put Taiwan-caught Tuna on its List of Goods Produced by Forced Labor

Last December, Greenpeace and 23 additional NGOs, trade unions, and businesses sent a letter to the US Department of Labor, Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) Office of Child Labor,…

-

Choppy Waters – Forced Labor and Illegal Fishing in Taiwan’s Distant Water Fisheries

DOWNLOAD THE REPORT Taiwan is one of the world’s largest distant water fishing (DWF) powers, with over 1,100 Taiwanese-flagged vessels fishing across our oceans and hundreds more Taiwanese-owned vessels flagged…

-

Greenpeace Sustainability, Labour & Human Rights, and Chain of Custody Asks for Retailers, Brand Owners and Seafood Companies

Greenpeace seeks a substantial transformation from fisheries production dominated by large-scale, socially and economically unjust, and environmentally destructive methods to prioritise smaller scale, community-based, labour intensive fisheries using ecologically responsible,…

-

Human Rights for Migrant Fishers

Abolish the Overseas Employment Scheme for Migrant Fishers and Expedite the Domestication of ILO Convention No. 188

-

The Two-Tiered System: Discrimination, Modern Slavery and Environmental Destruction on the High Seas

Greenpeace welcomes the opportunity to contribute to the Inaugural Plenary Meeting of the ILO SEA Forum for Fishers. The issue of discrimination in the global distant water fishing (DWF) industry…

-

Carting Away the Oceans 10

To view the report, click here. This 10th-anniversary edition of Carting Away the Oceans identifies which major supermarkets are leaders in sustainable seafood and which are falling behind. The findings are…

-

Greenpeace Report: Carting Away the Oceans

In June 2008, Greenpeace published the first edition…

-

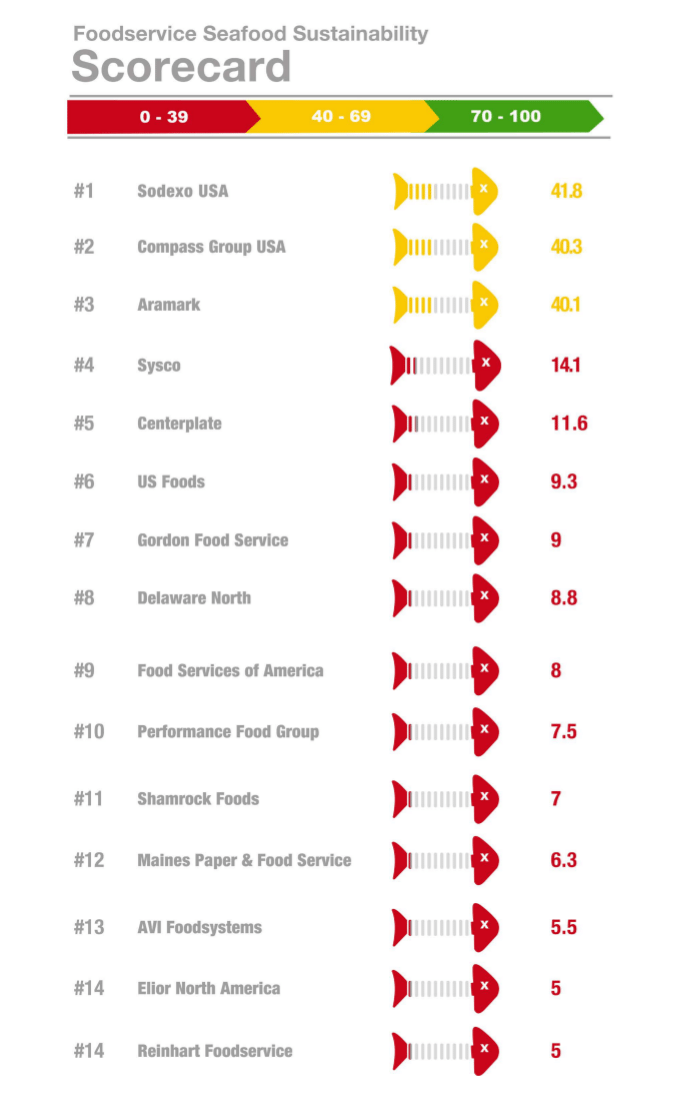

Sea of Distress 2017: The Foodservice Industry, Ocean Health, and Seafood Workers

Click here to download Sea of Distress 2017, Greenpeace’s second assessment of foodservice companies that feed millions of people every day who dine outside the home. Unfamiliar to many, companies…

-

Ray Hilborn: Overfishing Denier

Update, February 2019: Back in 2016, Greenpeace called out a well-known scientist named Ray Hilborn for failing to disclose the funding he’d received from the fishing industry in several of his…

-

Carting Away the Oceans 2015

Our Carting Away the Oceans report, released annually since 2008, identifies which major grocery chains are leaders in sustainable seafood and which are falling behind. The findings are telling. In…

-

Carting Away the Oceans 2014

Despite progress made by the retail sector overall, overfishing, destructive fishing, and illegal fishing are still major problems for ocean conservation and the economies of developing countries. Populations of the…

-

Carting Away the Oceans 7

There is still a great deal of work to be done, but let’s take a minute to raise a glass in acknowledgement of some of the truly remarkable stories of…

-

Taking Stock of Tuna

Tuna is the world’s favorite fish. It can be found from high-end sushi restaurants in Tokyo to family shopping trolleys in North American supermarkets and the dinner plates of Pacific island communities. With the world’s appetite for tuna now greater than what our oceans can sustain, tuna stocks globally are coming under pressure, suffering from…

-

Canned tuna’s hidden catch

Download document

-

Greenpeace investigation: Japan’s stolen whale meat scandal

A four-month-long undercover investigation by Greenpeace uncovers some of the whaling industry’s dirtiest secrets — including embezzlement of whale meat from the taxpayer-subsidized program.

-

Taking tuna out of the can

Tuna is one of the world’s favorite fish. It provides a critical part of the diet for millions of poor people, as well as being at the core of the…

-

Trading Away Our Oceans

Instead of pursuing further liberalization, states should ensure existing international law is implemented fully and establish new rules to ensure sustainable and equitable management of the high seas. Furthermore, developing…