Protect the Arctic

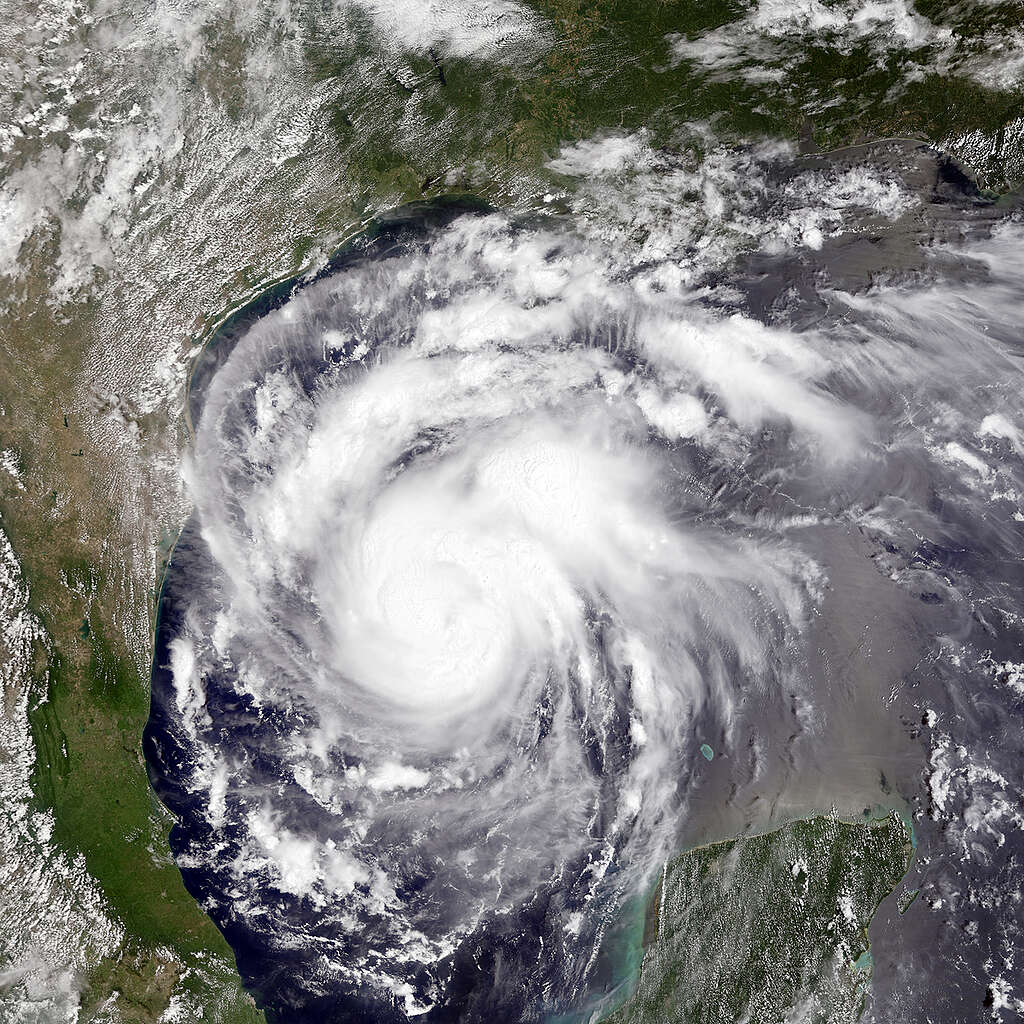

Climate change has already removed at least 75 percent of Arctic summer sea ice volume at rates never before experienced in human history. Soon, the Arctic Ocean will be like other oceans for much of the year: open water that is exposed to exploitation and environmental destruction.

Despite the Arctic Ocean’s unique vulnerabilities, it is still the least protected of all the world’s oceans. Less than 1.5 percent has any form of protected area status. The high seas of the Arctic — which belong to no single nation — are under no form of protection.

A strong Global Ocean Treaty will enable us to finally protect the Arctic Ocean, as part of a network of sanctuaries.

And we aren’t the only ones who want this. A Greenpeace survey revealed that 74 percent of people across 30 different countries support the establishment of a global sanctuary in the international waters around the North Pole. More than 70 percent of those people believed that the Arctic should be free of oil drilling and other heavy industry.

How do we envision an Arctic Sanctuary?

The Arctic ocean is vast, and its ecosystem depends on that immense size. An Arctic Sanctuary would need to be large as well. The Arctic high seas make up an area the size of the Mediterranean Sea.

Within the Arctic Sanctuary, there would be no fishing, military activity, or exploration for or extraction of fossil fuels or other minerals from the seabed.

Strict environmental controls would apply to all shipping in this area, although not all shipping activity would be prohibited. Heavy fuel oil use, for example, would not be allowed — a practice that is already adopted in Antarctic waters.

We will be pressuring the international community every chance we get. And our effort in collaboration with many organizations and Indigenous peoples’ to collect signatories for an Arctic Declaration in solidarity with Arctic peoples was a big step in this direction.

Arctic issues and threats

The fight to save the Arctic is heating up. The region is more impacted by global warming than any other place in the world. And as if the impacts of climate change weren’t enough, international oil companies have invested in exploiting the oil that lies deep in Arctic waters.

The people and animals that live in the Arctic depend on its unique ecosystem to survive. For them climate change is not a debate, it’s a daily reality. And with the region warming twice as fast as the rest of the world, Arctic ice is melting even faster, as the ocean absorbs the heat.

Read moreArctic Ocean drilling is a gamble with catastrophic consequences for the people, wildlife and the sensitive ecosystem of the region. And yet major companies like Shell and Exxon are making aggressive moves to usher in a new “oil rush” in the Arctic Ocean. Although the Obama administration made the Arctic Ocean off limits to offshore oil drilling for two years, those protections are at risk. We need a longer term fix. We need to keep the Arctic Ocean off-limits to oil drilling forever.

Read moreLearn more about…

California climate emergency

Extreme weather

Fossil fuel phase-out

Achieving the impossible

When we set out to protect the Arctic from destructive oil drilling and commercial fishing people told us it was impossible. Now after years of pushing millions of us have secured an enormous area protected from commercial fishing in the center of the Arctic Ocean. We’re getting closer every day to an Arctic safe from oil drilling too.

-

New Analysis of Five Major U.S. LNG Export Projects Finds Every One Fails the “Climate Test”

The new analysis shows that U.S. LNG export projects displace renewable energy and drive up emissions – making them incompatible with a livable climate

-

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

Beyond Fossil Fuels

You can see it in the vegetables growing in Arctic greenhouses, in wind turbines replacing diesel to power community microgrids, and in the spread of innovative educational initiatives. This future…

-

Scientific Integrity Complaint Regarding Arctic Oil Drilling Environmental Impact Statement

Greenpeace, the Center for Biological Diversity, and Friends of the Earth submitted a complaint under the Department of the Interior’s Scientific Integrity Policy requesting an investigation into the loss of…

-

A Review of the Impact of Seismic Survey Noise on Arctic Wildlife

Firing seismic airguns to find new oil reserves in the Arctic Ocean is ‘alarming’ and could seriously injure whales and other marine life, according to a new scientific review. The…

-

Untouchable: The Climate Case Against Arctic Drilling

There is a clear logic that can be applied to the global challenge of addressing climate change: when you are in a hole, stop digging. If we are serious about tackling…