Fossil fuel phase-out

A sustainable future for people, wildlife, and the climate cannot include fossil fuels.

The science is clear

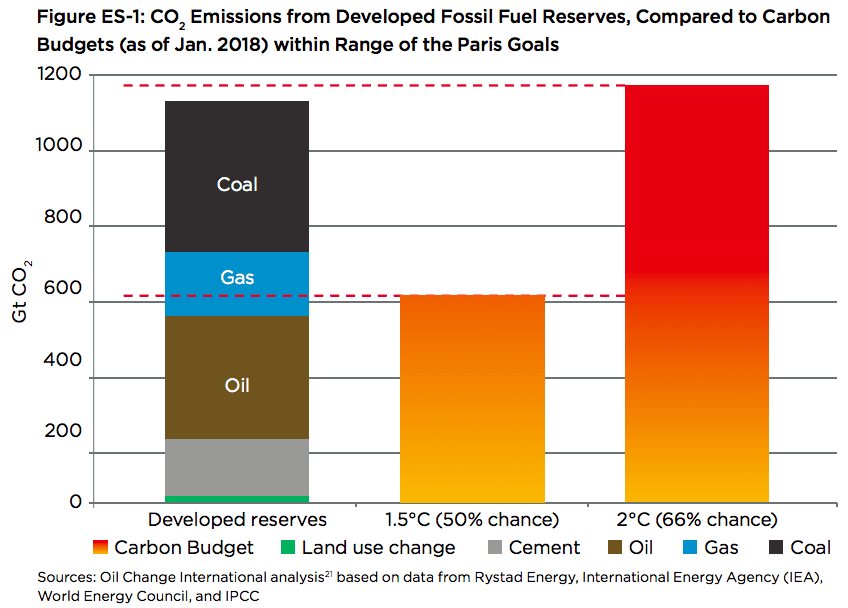

To avoid the worst impacts of climate change, we need to keep the majority of the world’s remaining fossil fuels in the ground. It’s time to phase out coal, oil, and natural gas — and instead, invest in workers, communities, and a renewable energy future.

The assessment of recent national energy plans and projections in the 2021 Production Gap Report’s uncovered that governments plan to produce around 110% more fossil fuels in 2030 than would be consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5°C, and 45% more than would be consistent with limiting warming to 2°C, on a global level. In short, if governments extract and burn the amount of oil, gas, and coal that they are currently planning to, we will not stand a chance at avoiding a climate catastrophe.

There are solutions

The US government can start by no longer allowing fossil fuel companies to drill and mine on our public lands. A 2018 report by the Department of the Interior estimated that between 2005-2014 emissions from fossil fuels produced on Federal lands represent, on average, 23.7% of national emissions for carbon dioxide, 7.3% for methane, and 1.5% for nitrous oxide.

Congress must stop funding climate destruction with our hard earned tax dollars. Our government gives away $15 billion in public money every year to fossil fuel corporations through tax breaks, subsidies, and handouts. It’s time to shift that investment to the clean, just energy system of the future and to support communities in the transition away from oil, gas, and coal.

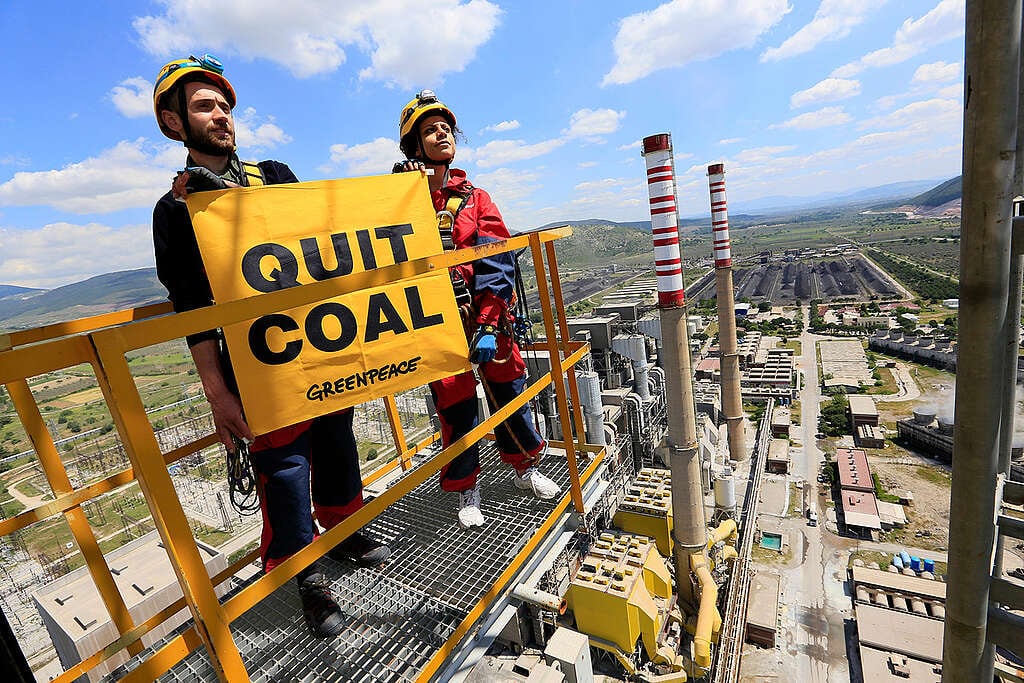

It’s time to quit coal

There is no such thing as clean coal. There’s a reason that coal has been singled out in the fight to keep fossil fuels in the ground. It’s one of the most polluting energy sources out there, the single largest contributor to global warming, and makes us sick by polluting our air and water with toxic pollution, like mercury.

Coal production and jobs are at its lowest levels in over 50 years. In 2020 there were less than 45,000 coal miners in the U.S. That same year over 230,000 Americans worked in solar and wind energy is cheaper than coal power in many U.S. states.

As we complete the transition off of coal, we must ensure that the workers and communities are not left behind by greedy coal barons who try to cut and run.

Coal was once king in the United States, accounting for more than 40 percent of our electricity as recently as 2014. The good news is people around the world are moving away from dirty, polluting coal in favor of clean, renewable, affordable energy. Right now, we have the chance to quit coal for good and keep remaining U.S. coal reserves in the ground.

More about coalThe last thing the world needs is more oil. As with other fossil fuels, our reliance on oil is fueling climate change, polluting priceless landscapes, and costing billions of dollars. The US government has subsidized coal, oil, and gas for decades, despite the fact that a majority of voters want to end fossil fuel subsidies. Fossil fuel companies are fighting to keep oil on life support, but we’re fighting back.

We’ve got great opportunities today to build a cleaner energy system in time to avoid the worst impacts of climate change — and oil has no part in it.

Fracking is the fossil fuel industry’s latest false solution to our energy challenge. It’s more expensive, more polluting, and more dangerous than clean, renewable energy. Fracking is diverting money and attention from the real long-term solutions we need for a sustainable energy system, while adding to greenhouse gas pollution and environmental degradation.

So why are we pursuing fracking in the first place?

No Offshore Drilling

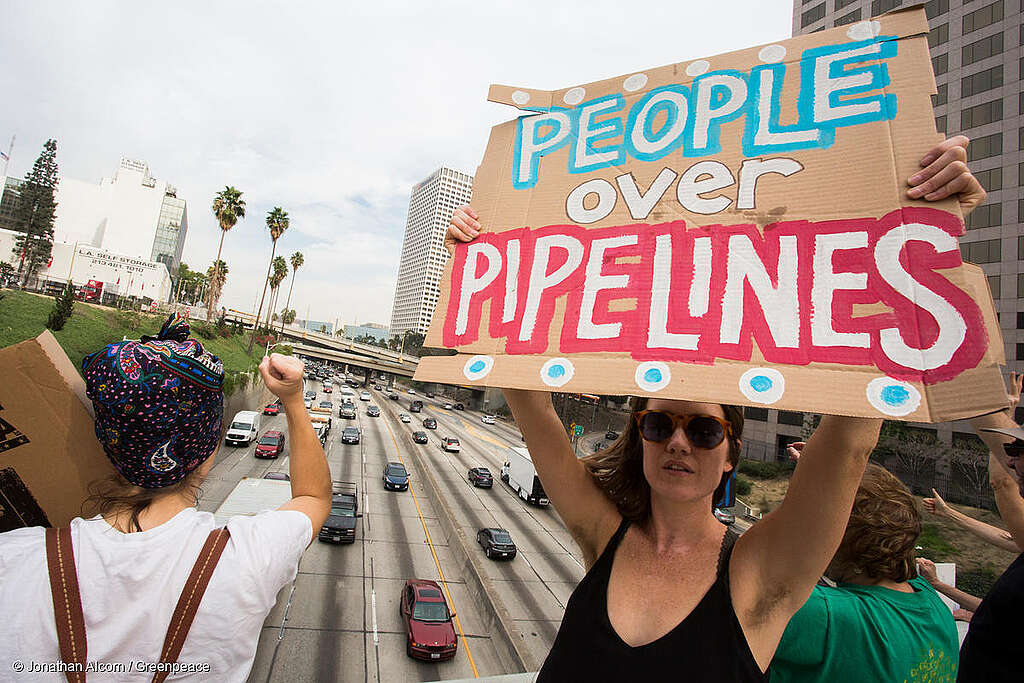

Our public lands aren’t the only critical battleground in the fight to phase out fossil fuels — offshore oil and gas drilling is a growing threat to our health and climate.

Big oil companies have profited from the exploitation of U.S. public land and water for decades. Their activities have not only devastated land and water that belongs to American taxpayers, but also pushed us steadily closer to climate chaos.

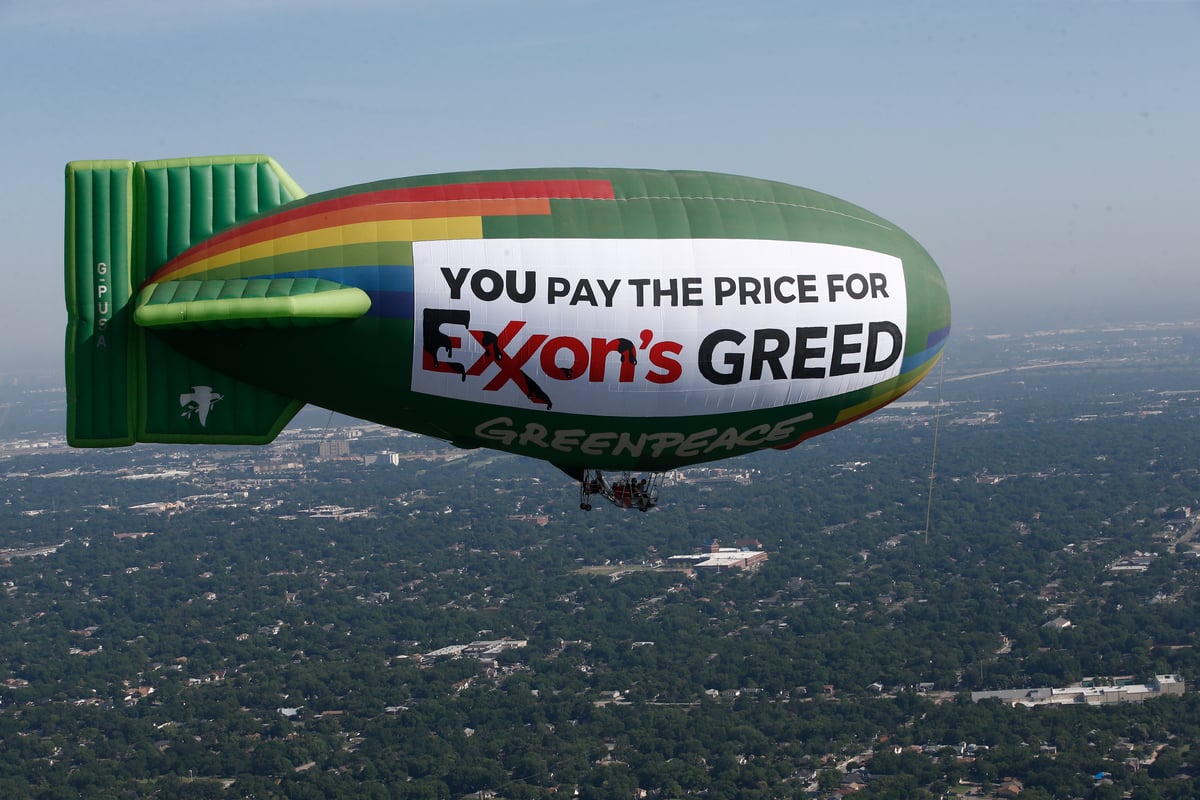

The industry’s greed only grows, fed by a clamor to exploit oil and gas reserves and continue to profit at the expense of people, wildlife, and the climate.

Take the Arctic, for example. Due to global warming and melting sea ice, the oil deep in Arctic waters is now accessible for the first time. Corporations like Shell, ExxonMobil, and BP want to drill for it.

That’s right — oil that was once out of reach in frozen areas of the Arctic is now accessible because of the climate crisis. And the very companies responsible for the ice melting want more oil to make the climate crisis worse.

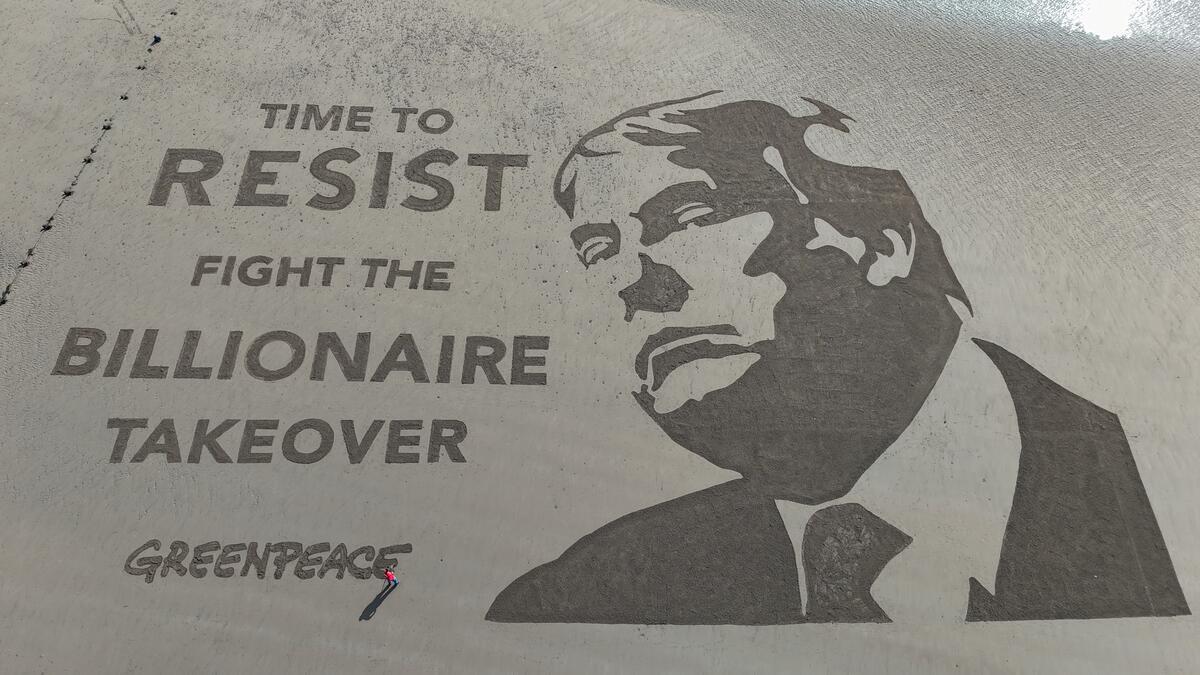

The good news is that your resistance has kept Arctic oil safe thus far. An incredible global movement forced Shell out of the Arctic in 2015 and prompted President Obama to make the U.S. Arctic off limits to oil drilling for two years. The Trump administration rolled back many of the protections. It is now up to President Biden to not just restore Obama era protections, but install a lifetime ban on arctic drilling. Things look to be trending in the right direction, in 2021 a federal district court decision halted the ConocoPhillips’ Willow Master Development Plan in the Alaskan Arctic.

Learn more about…

Ending subsidies

The climate emergency

-

New Analysis of Five Major U.S. LNG Export Projects Finds Every One Fails the “Climate Test”

The new analysis shows that U.S. LNG export projects displace renewable energy and drive up emissions – making them incompatible with a livable climate

-

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Wrecking the future: the Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities

Wrecking the future: The Trump war on the ocean, climate, and communities. Dismantling climate and oceans protections.

-

Department of Energy’s go-to firm helped prepare Alaska LNG’s bogus climate assessment

Greenpeace USA research reveals that the authorization was granted on the basis of a deeply flawed environmental analysis, and consultants who supported the analysis had ties to the gas industry.

-

Permit To kill: Potential health and economic impacts from U.S. LNG export terminal permitted emissions

Research from Sierra Club and Greenpeace USA shows that permitted emissions from LNG terminals are associated with major public health costs.

-

Briefing: U.S. Oil and Gas Companies Set to Make Tens of Billions More from Wartime Oil Prices in 2022

As American families continue to be hammered by skyrocketing gasoline prices, U.S. oil and gas companies are poised to reap tens of billions in windfall profits thanks to high wartime…

-

8 reasons why we need to phase out the fossil fuel industry

Fossil fuel corporations are profiting from the continued consumption of coal, oil and gas, which are driving global warming to dangerous levels. A Greenpeace report illustrated the need for managed…

-

The Climate Emergency Unpacked: How Consumer Goods Companies are Fueling Big Oil’s Plastic Expansion

As the climate crisis intensifies, there is growing worldwide acceptance of the need to slash greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the burning of fossil fuels to limit global heating to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels

-

President Biden’s 100 Day Climate Progress Report

Numerical metrics are based on the following “progress bar” that represents steps toward full implementation, with weightings derived from the #Climate2020 Scorecard. Phasing Out Fossil Fuels 1. Lead a Managed Fossil…

-

Fossil Fuel Racism: How phasing out oil, gas, and coal can protect communities

Fossil fuels — coal, oil, and gas — lie at the heart of the crises we face, including public health, racial injustice, and climate change. This report synthesizes existing research and provides new analysis that finds that the fossil fuel industry contributes to public health harms that kill hundreds of thousands of people in the…

-

Reusables are doable

It is time to stop treating people and the planet as disposable. To save our climate and ensure healthy communities for everyone, we must end our reliance on cheap throwaway plastics.

-

Greenpeace USA Submission to the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis

In November 2019, Greenpeace USA submitted these recommendations to the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. Read the full submission here. Introduction Greenpeace USA appreciates the opportunity to inform…

-

Policy Briefing: Remediation of Orphan Oil & Gas Wells in COVID-19 Stimulus

A new policy briefing from Greenpeace USA calls on Congress to provide funding to close the backlog of orphaned oil and gas wells, strengthen policies around well bonding and retirement,…

-

Meet the Oil Executives Visiting the White House to Discuss ‘Relief’ for the Industry With Trump

Tomorrow, executives from at least seven US oil companies will meet with Donald Trump at the White House to discuss relief for the oil industry. As reported by the Wall…

-

Toxic Air: The Price of Fossil Fuels

A new report from Greenpeace Southeast Asia and the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) found that air pollution from burning coal, oil, and natural gas accounts…

-

Greenpeace Report: Real Climate Leadership

The next president and Congress must adopt policies to phase out domestic fossil fuel production as part of any comprehensive climate policy effort like a Green New Deal. This fossil fuel phase out should occur in tandem with policies to boost renewable energy and ensure a just transition for workers, communities and tribal nations. This…

-

Meet the Fourteen House Members Who Pump Most Of Our Oil

Ten Republicans and four Democrats represent the parts of the country where the vast majority of U.S. crude oil is produced. As the 116th Congress gets down to work, we…

-

Beyond Fossil Fuels

You can see it in the vegetables growing in Arctic greenhouses, in wind turbines replacing diesel to power community microgrids, and in the spread of innovative educational initiatives. This future…

-

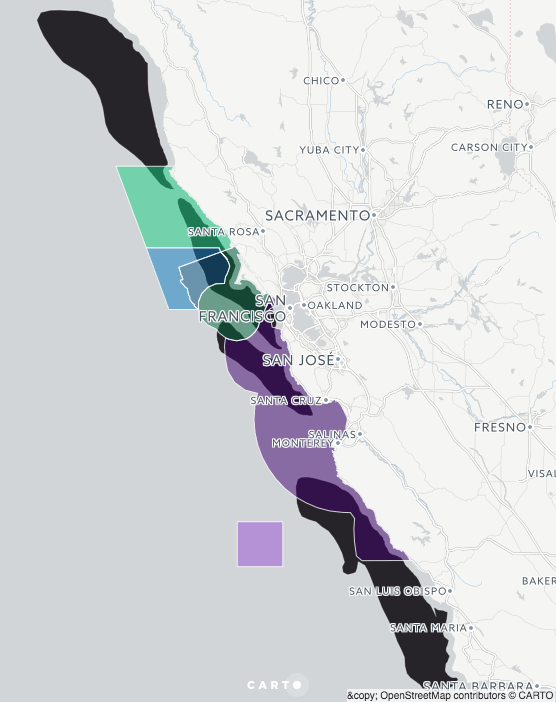

California National Marine Sanctuaries Under Trump Review Contain Sizable Oil and Gas Deposits

Summary Findings Expansions of National Marine Sanctuaries (NMS) off the California coast ordered by Presidents Bush and Obama are currently under review by the Trump administration. A geospatial analysis has…

-

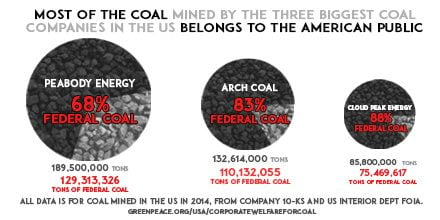

Corporate Welfare for Coal

Download the full report — Corporate Welfare for Coal: The biggest coal mining companies depend on subsidized federal coal, even as they attack federal climate and clean air policies The coal industry…

-

Third Financial Quarter Coal Market Report: Risks to U.S. Coal Mining and Export Proposals (October 2015)

All prices are in USD unless otherwise noted. The information in the report is not financial advice, investment advice, trading advice or any other advice. This report was prepared by: Greenpeace, Sierra…

-

Coal Market Report – Risks to US coal mining and export proposals, July 2015

The US coal industry is facing structural decline and companies pursuing coal export proposals in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) are particularly at risk. This update highlights execution risks for PNW…

-

Carbon Capture SCAM

Supporters of carbon capture for oil extraction claim that oil produced with CO2 injection is going to get produced somewhere else anyway, and therefore would actually be ‘green’ oil because it keeps CO2 from…

-

Case studies: The impacts of extracting and burning natural gas

Numerous studies have shown that the processes of extracting and burning natural gas, including fracking, have grave environmental impacts. Here are a few of them.

-

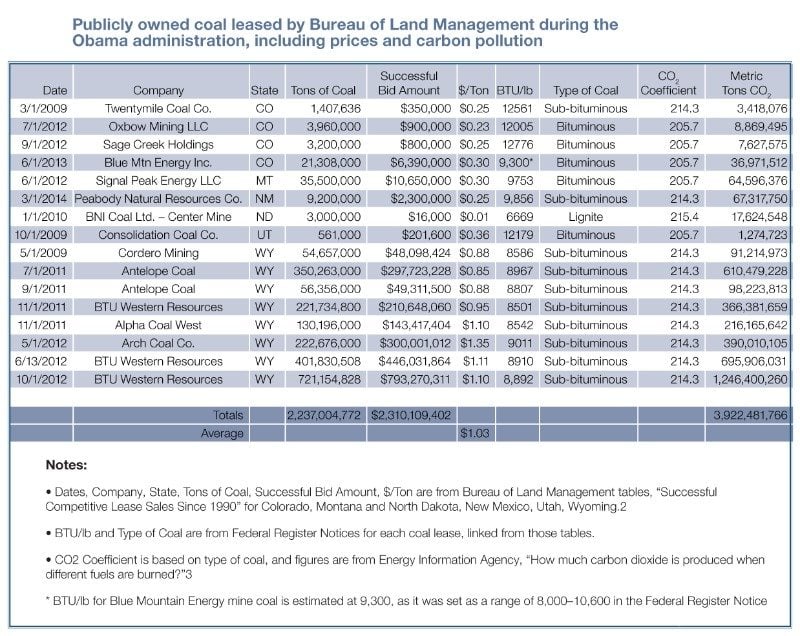

Leasing Coal, Fueling Climate Change

Download the PDF of “Leasing Coal, Fueling Climate Change” This question is especially important in light of a recent federal court ruling, which blocked plans to expand a coal mine…

-

The Myth of China’s Endless Coal Demand

The US coal industry – reeling from sagging domestic demand, plummeting profits, and tanking stock prices – is desperate for a new market for its wares, and it thinks it has found one in China. But in reality, the Chinese market for US coal exports may dry up before major new US coal shipments ever…

-

Donors Trust: Laundering Climate Denial Funding

Findings: Donors Trust and its associated organization, Donors Capital Fund, have funded 102 climate-denial organizations since 2002. From 2002 to 2011, Donors Trust and Donors Capital Fund have provided $146…

-

Polluting Democracy

The majority of the ancient US coal fleet has not installed easily available technology that could reduce mercury pollution by 90%. Coal combustion is responsible for most US mercury pollution.…

-

Deepwater Horizon – One Year On

He further announced research to assess the feasibility of offshore drilling in theBeaufort and Chukchi seas off the north coast of Alaska.

-

![Greenpeace Energy [R]evolution 2010](https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-usa-stateless/2024/11/4496f0b9-energy-rev-250px.jpg)

Greenpeace Energy [R]evolution 2010

Download document

-

The True Cost of Coal

Traditionally considered the cheapest fuel around, the market price for coal ignores its most significant impacts. These so-called “external costs” manifests themselves as damages such as respiratory diseases, mining accidents,…