Fracking

Fracking is the fossil fuel industry’s latest false solution to our energy challenge. It’s more expensive, more polluting, and more dangerous than clean, renewable energy. So why are we pursuing fracking in the first place?

What is Fracking?

Since 2005, more than 100,000 oil and gas wells have been drilled and fracked in the United States.

Fracking has been pursued by countries like Canada, India, the U.K., and China, and in numerous U.S. states.

Fracking is short for hydraulic fracturing. It’s an industrial process that breaks apart rock formations deep underground to extract fossil fuels like oil and methane gas. Because this oil and gas is found in rock formations called shale, these fuels are usually called shale oil or shale gas.

Hydraulic fracturing is a process done after a well has been drilled but before oil and gas can be brought from the well. The term fracking has come to describe the entire process of creating a fracked well, from drilling the initial hole through the hydraulic fracturing stage and the production of fossil fuels.

While fossil fuel companies claim fracking has been practiced safely for decades, we actually know very little about its long-term environmental impacts. Changes in technology and economics have allowed fossil fuel companies to frack on a much larger scale than has ever been done before, making today’s fracking a much different process than in years past. Behind the scenes, these same companies have warned their investors that fracking carries the risk of chemical leaks, spills, explosions and other environmental damage, not to mention serious injury to workers.

New technology is making fracking more dangerous, more profitable, and more attractive to fossil companies, but no less damaging to the environment and human health.

The dangers of fracking

Fracking is a water-intensive process. In water-scarce states like Texas and Colorado, more than 3.6 million gallons of water are used every time a well is fracked, which can happen multiple times throughout the life of a well.

The process involves injecting a huge quantity of fresh water mixed with toxic chemicals — called fracking fluids — deep into the ground. Fossil fuels companies routinely claim that these fracking fluids are harmless because they’re roughly 2 percent chemical and 98 percent. But 2 percent of the billions of gallons of fracking fluid created by drillers every year equals hundreds of tons of toxic chemicals, many of which are kept secret by the industry.

Even worse, the oil and gas industry has no idea what to do with the massive amount of contaminated water it’s creating. Fracking fluids and waste have made their way into our drinking water and aquifers. Fracking has already been linked to drinking water contamination in Pennsylvania, Colorado, Ohio, Wyoming, New York, and West Virginia.

An EPA draft report released in 2015 found more than 150 instances of groundwater contamination due to shale drilling and fracking.

Homeowners in some affected areas even report being able to light the water coming out of their kitchen sinks on fire due to gas contamination.

While the fossil fuel industry denies it, the EPA has acknowledged the connection between fracking and increased earthquakes since 1990.

Scientists have made firm links between earthquakes in Colorado, Oklahoma, Ohio, and Arkansas in the past few years.

Oklahoma, for example, averaged 21 earthquakes above a 3.0 magnitude per year between 1967 and 2000. Since 2010 and the beginning of the fracking boom, the state has averaged more than 300 earthquakes above 3.0 magnitude every year.

Most of these earthquakes are caused by underground injection wells, which are used to dispose of contaminated water created by the fracking process. These wells do not produce the gas and oil. However, the shale industry creates so much contaminated wastewater — and has so few options for disposing of it — that injection wells have become a critical part of shale drilling and fracking.

Because shale drilling and fracking is understood so poorly and regulated so little, we don’t know exactly how much air pollution is leaking from fracking wells across the country. States like Colorado have seen tremendous spikes in air pollution due to fracking wells.

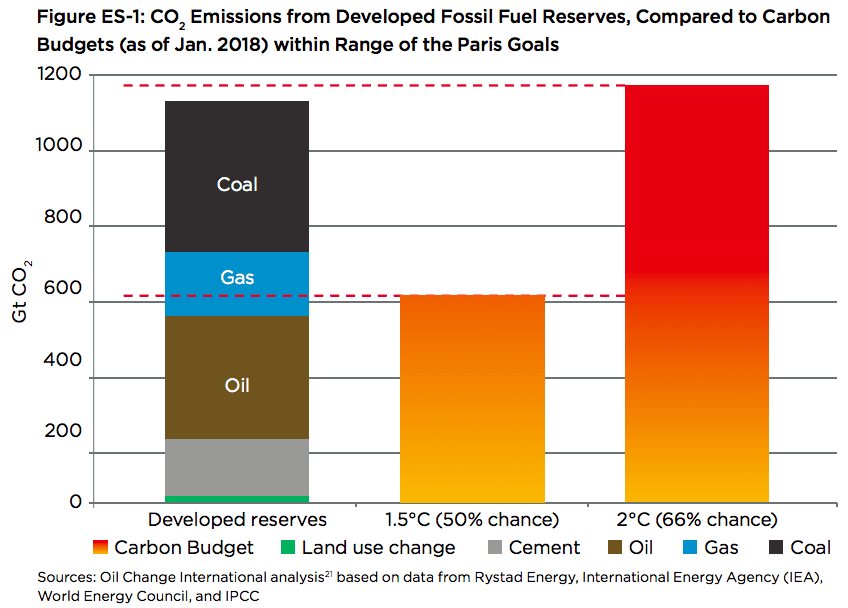

And one of the most troubling aspects of shale drilling and fracking is its impact on the climate.

Methane gas — the main component of natural gas — is a less common but more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. In fact, it’s 85 to 105 times more powerful than carbon dioxide at disrupting the climate over a 20-year period.

There is still no consensus as to how much methane is leaking into the air due to shale drilling and fracking, but some studies suggest it could be worse than burning coal for the climate.

Let’s ditch fracking for clean energy

Fracking is diverting money and attention from the real long-term solutions we need for a sustainable energy system, while adding to greenhouse gas pollution and environmental degradation.

Join us in telling government and big business to stop pursuing this false solution and start focusing on the energy future we want, one based on clean and renewable energy.

Learn more about fracking

Earthquakes

Recycled Fluid

Water

Predatory companies

Regulatory failures and delays

-

New Analysis of Five Major U.S. LNG Export Projects Finds Every One Fails the “Climate Test”

The new analysis shows that U.S. LNG export projects displace renewable energy and drive up emissions – making them incompatible with a livable climate

-

Failing the climate test: LNG projects awaiting final investment decision do not stand up to U.S. Government analysis

Read the report: Download “Failing the “Climate Test.” The multi-volume analysis, termed the 2024 LNG Export Study, represents the most comprehensive government assessment to-date of the energy, economic, and environmental impacts of U.S. LNG exports.

-

The ‘Big, Beautiful’ Blunder: a bill that will live in infamy

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 1, 2025)—In response to the passage of the “Big Beautiful Bill” in the United States Senate, Greenpeace USA Deputy Climate Program Director, John Noël, said: “This is…

-

Failing the climate test: LNG projects awaiting final investment decision do not stand up to U.S. Government analysis

Read the report: Download “Failing the “Climate Test.” The multi-volume analysis, termed the 2024 LNG Export Study, represents the most comprehensive government assessment to-date of the energy, economic, and environmental impacts of U.S. LNG exports.

-

Energy Transfer vs. Greenpeace trial analysis

Here is what you need to know about the Energy Transfer vs. Greenpeace trial.

-

Department of Energy’s go-to firm helped prepare Alaska LNG’s bogus climate assessment

Greenpeace USA research reveals that the authorization was granted on the basis of a deeply flawed environmental analysis, and consultants who supported the analysis had ties to the gas industry.

-

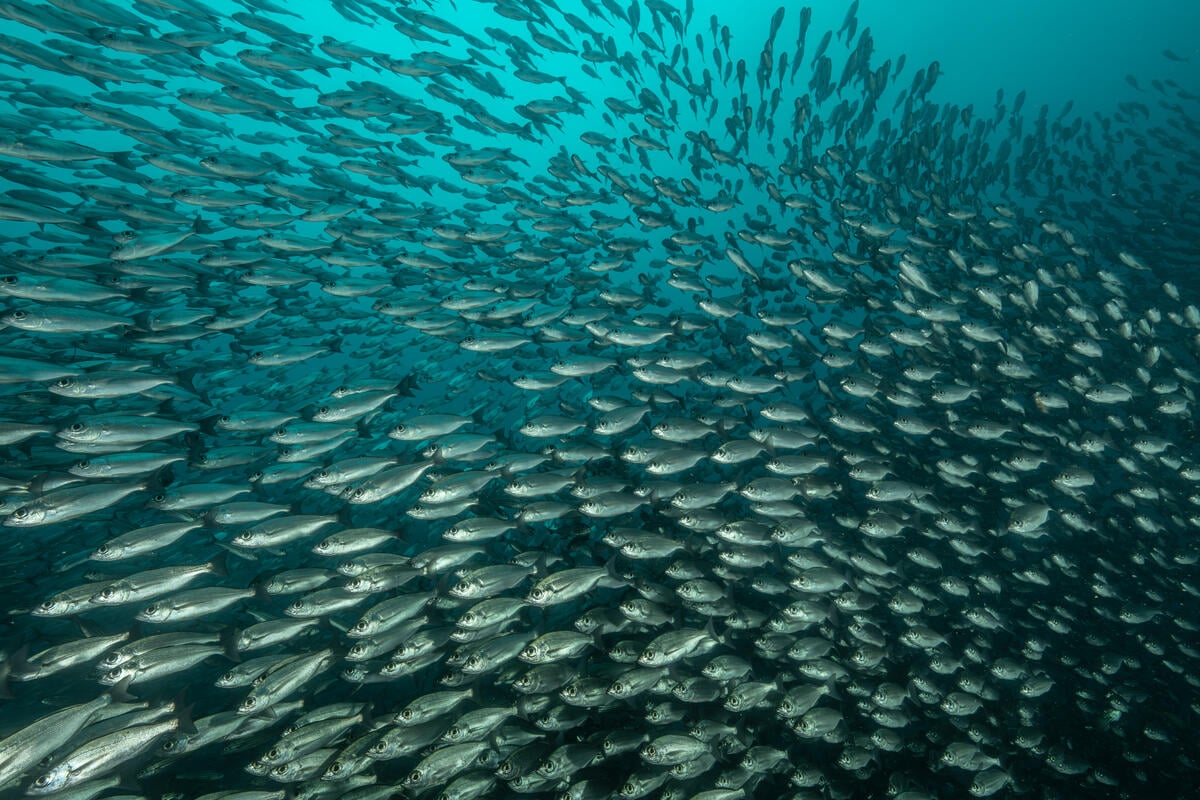

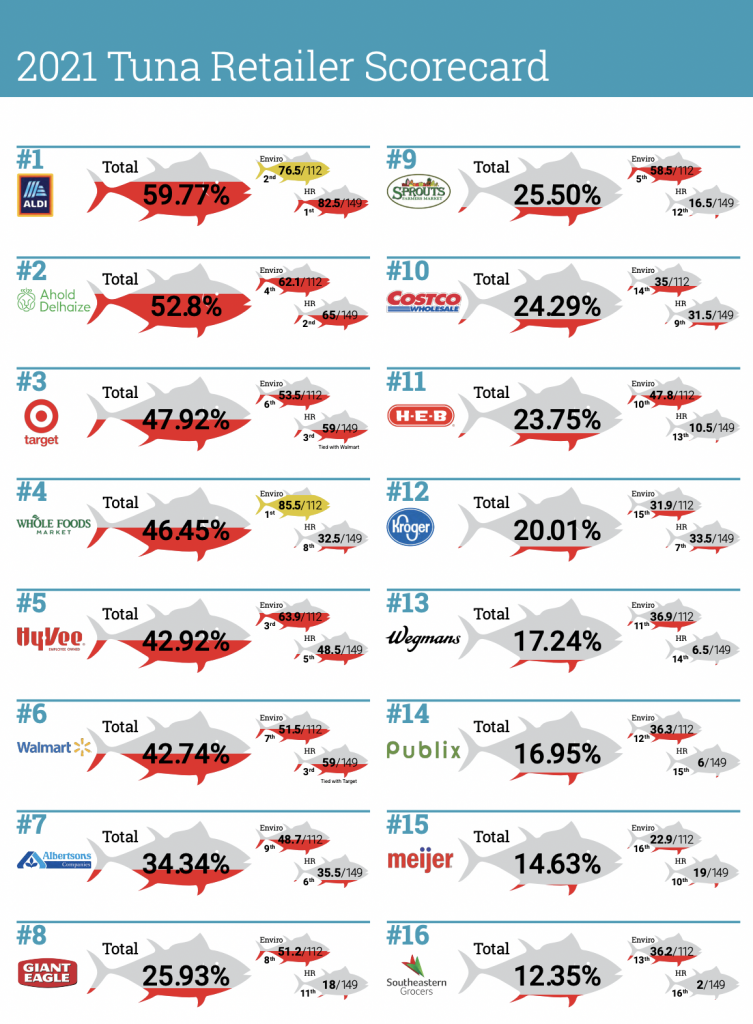

The high cost of cheap tuna: US supermarkets, sustainability, and human rights at sea (3rd edition)

In Greenpeace USA’s third scorecard measuring the human rights and sustainability practices of 16 major US supermarkets’ tuna supply chains, only two retailers achieved a passing score.

-

Permit To kill: Potential health and economic impacts from U.S. LNG export terminal permitted emissions

Research from Sierra Club and Greenpeace USA shows that permitted emissions from LNG terminals are associated with major public health costs.

-

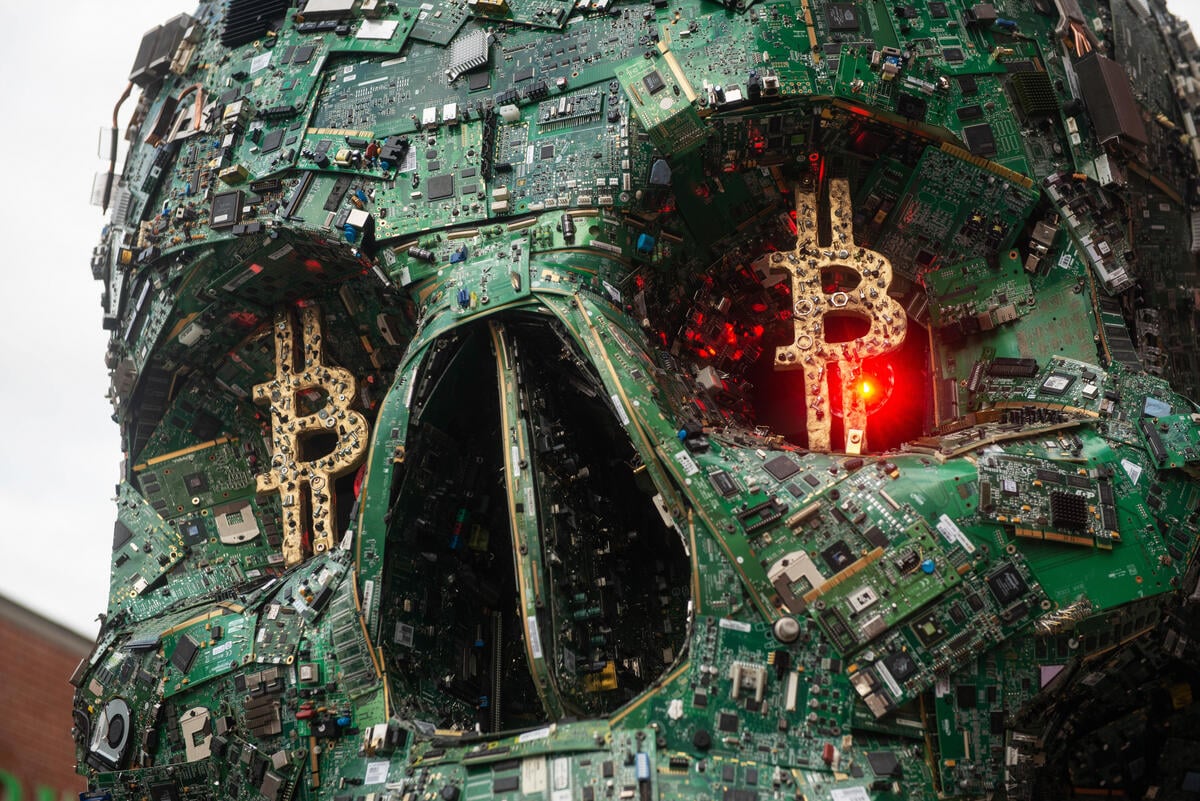

Bankrolling Bitcoin pollution: How Big Finance supports a new climate threat

Bitcoin mining has grown into a big commercial industry dominated by publicly traded companies that operate large-scale mining facilities that often use as much electricity as a small city. In…

-

Department of Energy used gas industry insiders and consultants to build the case for soaring LNG exports

Overview For roughly the past decade, in the absence of a specifically articulated policy for reviewing liquefied natural gas (LNG) export applications, the Department of Energy (DOE) has adopted a…

-

Mining for power: connection between Bitcoin miners, corporate interest groups, and climate deniers

Introduction Greenpeace USA research reveals how the Bitcoin mining industry is interconnected with the fossil fuel and other polluting industry groups and climate denialists that oppose needed action to address…

-

What Biden’s LNG Pause Does and Doesn’t Do

Today the Biden-Harris Administration announced a “pause” on new export approvals for liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects, while the Department of Energy (DOE) reviews its LNG export policy. This is…

-

Polluting Bitcoin mines come to rural Georgia

Cleanspark’s Bitcoin boom in rural Georgia, backed by Wall Street giants, raises environmental and social concerns challenging the promised benefits to rural communities.

-

Dollars vs. Democracy 2023

Americans overwhelmingly support government action on the climate crisis. As a result, the fossil fuel industry has expanded its playbook…

-

Riot Platforms: The Company Behind the Most Energy Intensive Bitcoin Mine in the U.S.

Summary Riot Platforms is leading the polluting Bitcoin boom in Texas. The company operates the largest, and one of most energy and carbon-intensive, Bitcoin mines in the U.S. at their…

-

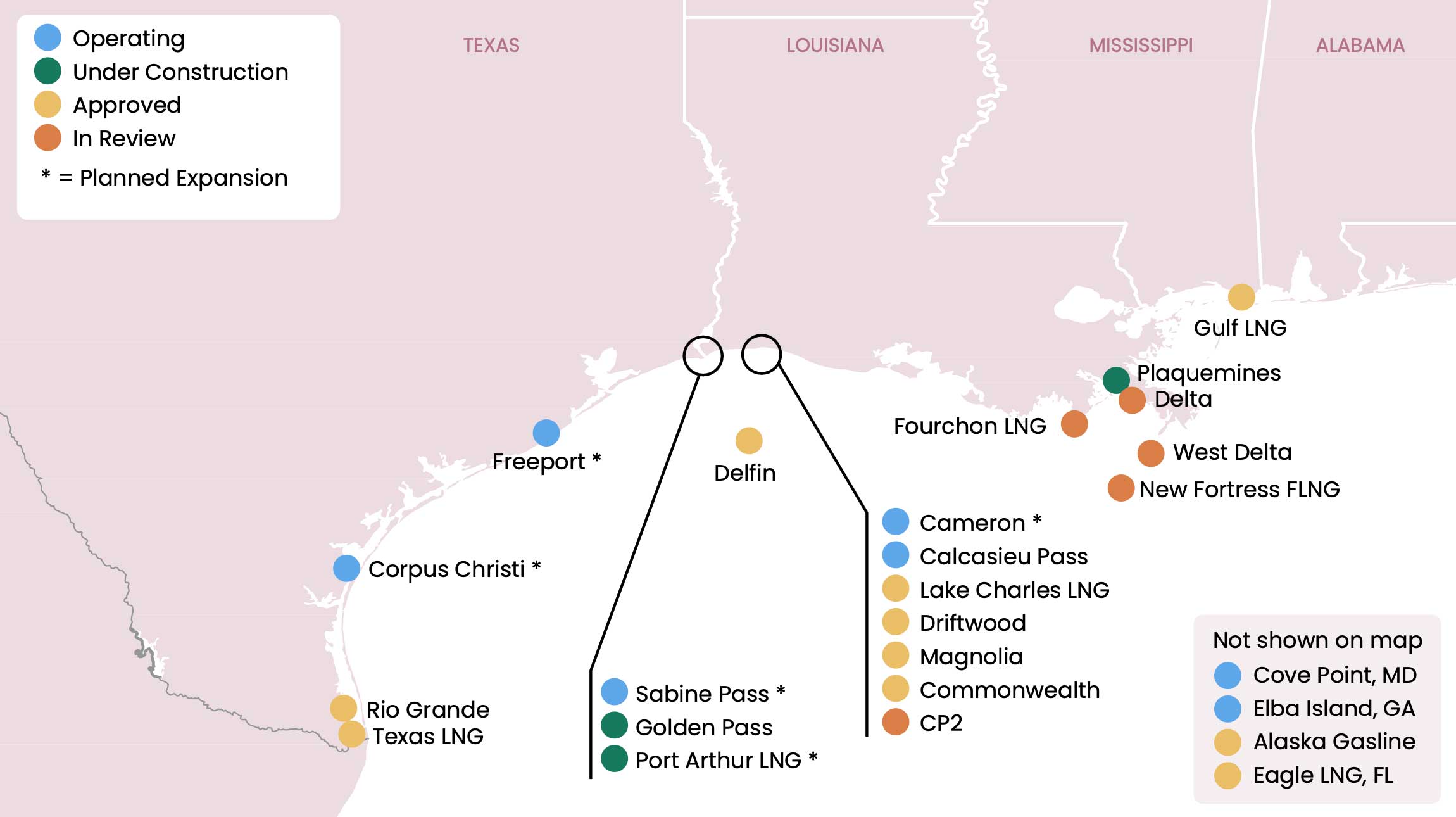

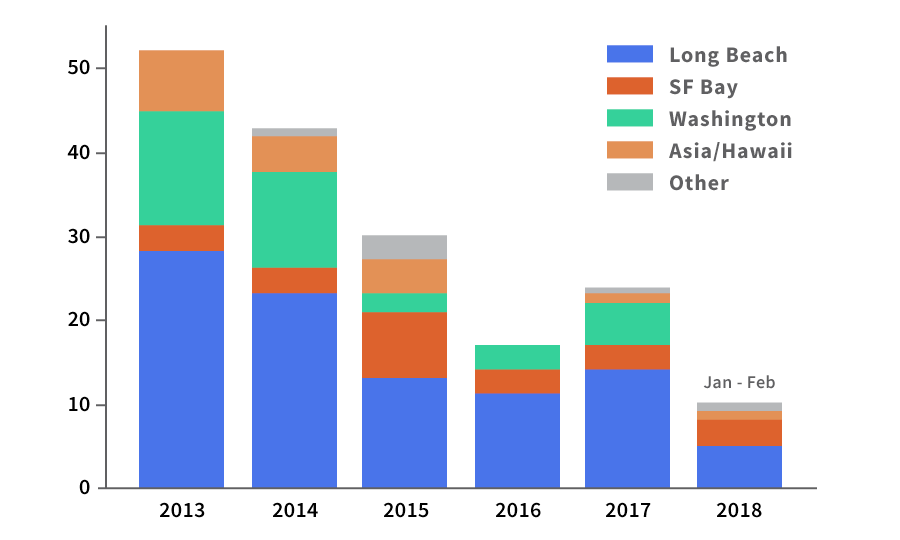

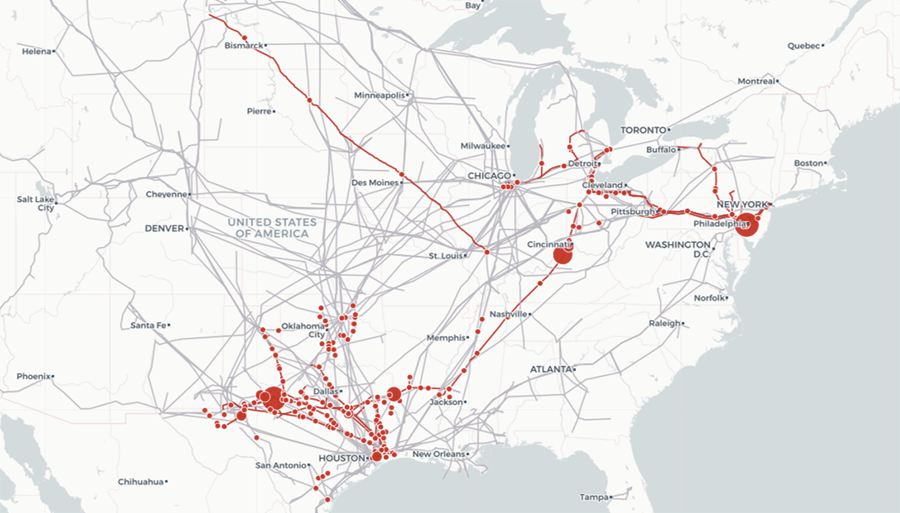

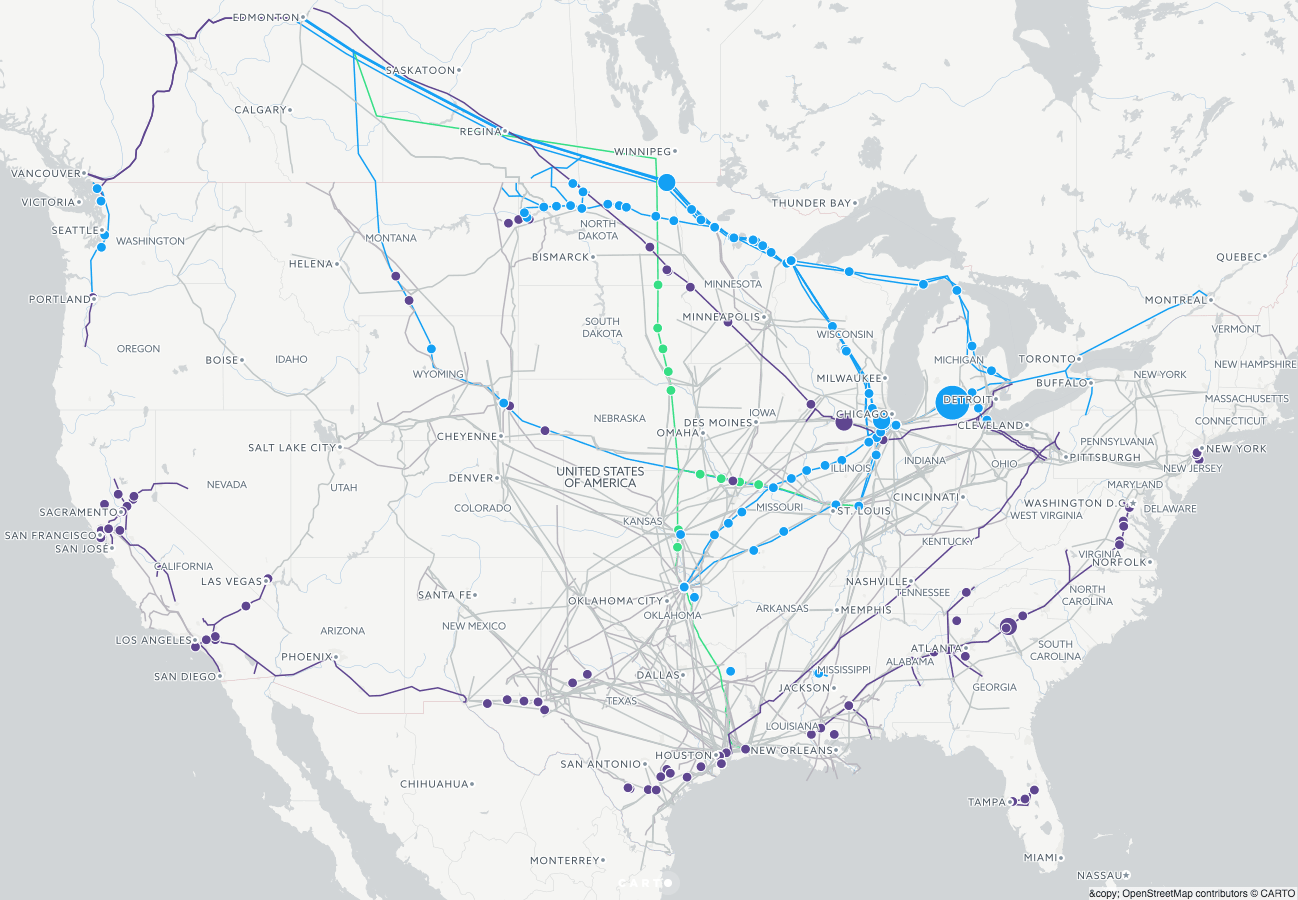

LNG Tanker Tracker

The U.S. recently became the world’s leading exporter of liquified natural gas (LNG). Much of that is exported via the Gulf Coast from facilities in Texas and Louisiana. Greenpeace USA…

-

Investing In Bitcoin’s Climate Pollution

Bitcoin consumes as much electricity as entire countries, and 62% of the electricity used for Bitcoin mining globally in 2022 came from fossil fuels. Bitcoin’s energy-hungry technology has revived decommissioned…

-

Gulf Coast Terminal Build Out

Methane gas is converted into Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and then loaded onto tankers at large, complex export terminals. The scale of LNG exports is limited by the capacity of…

-

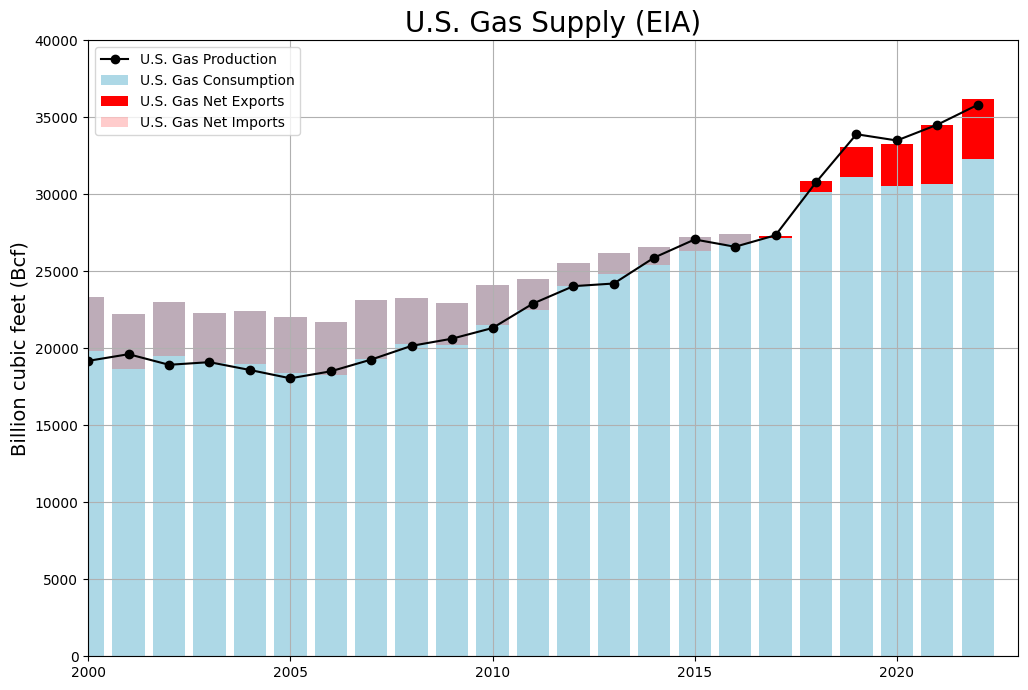

What are LNG Exports?

Methane or fossil gas (usually called “natural” gas in the U.S.) is a fossil fuel that is used to generate electrical power, heat buildings, and power heavy industry. Thanks to…

-

Liquefied Natural Gas Exports 101

In recent years, the United States has become the world’s largest oil and gas driller, and an increasing amount of fossil gas production is being directly exported to other countries…

-

Forever Toxic: The science on health threats from plastic recycling

Without dramatically reducing plastic production, it will be impossible to end plastic pollution and eliminate the health threats from chemicals in plastics.

-

Media Briefing: U.S. Liquefied Gas Flooding Europe

The oil and gas industry has moved quickly to take advantage of the disruptions caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In 2022, a surge of shipments of liquefied natural gas…

-

Too Fast For Gas: Problems at Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass Should Not Be Overlooked

Last month, Venture Global told regulators and customers that issues with the Calcasieu Pass LNG facility will delay the start of commercial operations. They described the issues as “failures in…

-

Financial Institutions Need to Support a Code Change to Cleanup Bitcoin

Introduction “Humanity is on thin ice — and that ice is melting fast…Our world needs climate action on all fronts — everything, everywhere, all at once.” United Nations Secretary-General Antonio…

-

The High Cost of Cheap Tuna: US Supermarkets, Sustainability, and Human Rights at Sea

Published: 02-13-2023 Edition: 2nd Download: PDF A net bulging with tuna and bycatch on the Ecuadorean purse seiner ‘Ocean Lady’, which was spotted by Greenpeace in the vicinity of the northern Galapagos Islands while using fishing aggregating devices (FADs). Around 10% of the catch generated by purse seine FAD fisheries is unwanted bycatch and includes…

-

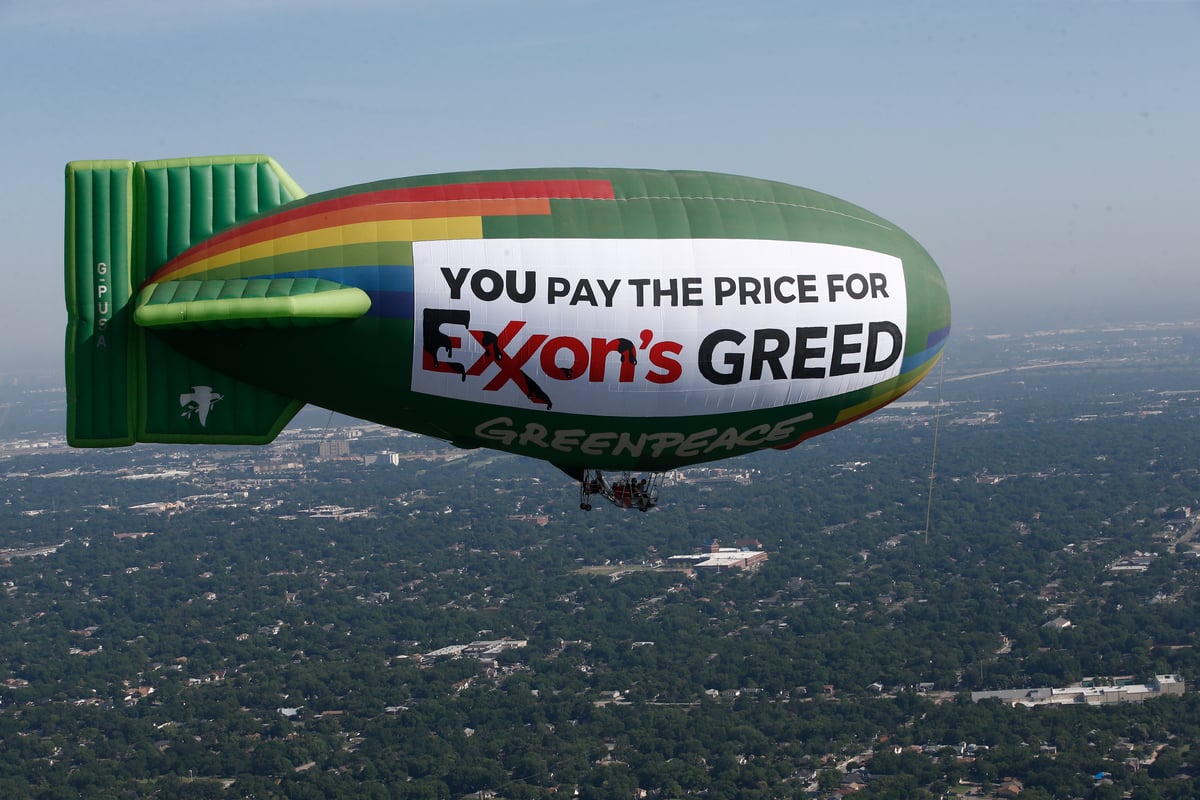

Big Oil Money Looms Large in Competitive Elections

During this election cycle, 20 oil & gas companies and industry trade associations contributed more than $52 million to right-wing super PACs and party fundraising committees, and more than $4…

-

Circular Claims Fall Flat Again

A recent Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report projects that global plastic use and waste will nearly triple by 2060 with a meager increase in plastic recycling, resulting in a doubling of global plastic pollution. The United States Department of Energy (U.S. DOE) estimated that the volume of plastic waste in the U.S.…

-

Fake My Catch: The Unreliable Traceability in our Tuna Cans

US seafood company Bumble Bee, one of the leading companies in the canned tuna market with nearly 90% consumer awareness levels, and its Taiwanese parent company Fong Chun Formosa Fishery Company (hereinafter referred to as FCF), one of the top three global tuna traders, play an important role in the global tuna industry, and thus…

-

Madness Is The Method: How Cheniere is Greenwashing its LNG With New Cargo Emissions Tags

Full Report Download English Full Report Follow the story: The initial Life-Cycle Assessment paper Our letter to the editor commenting on their paper Their reply to…

-

Briefing: U.S. Oil and Gas Companies Set to Make Tens of Billions More from Wartime Oil Prices in 2022

As American families continue to be hammered by skyrocketing gasoline prices, U.S. oil and gas companies are poised to reap tens of billions in windfall profits thanks to high wartime…

-

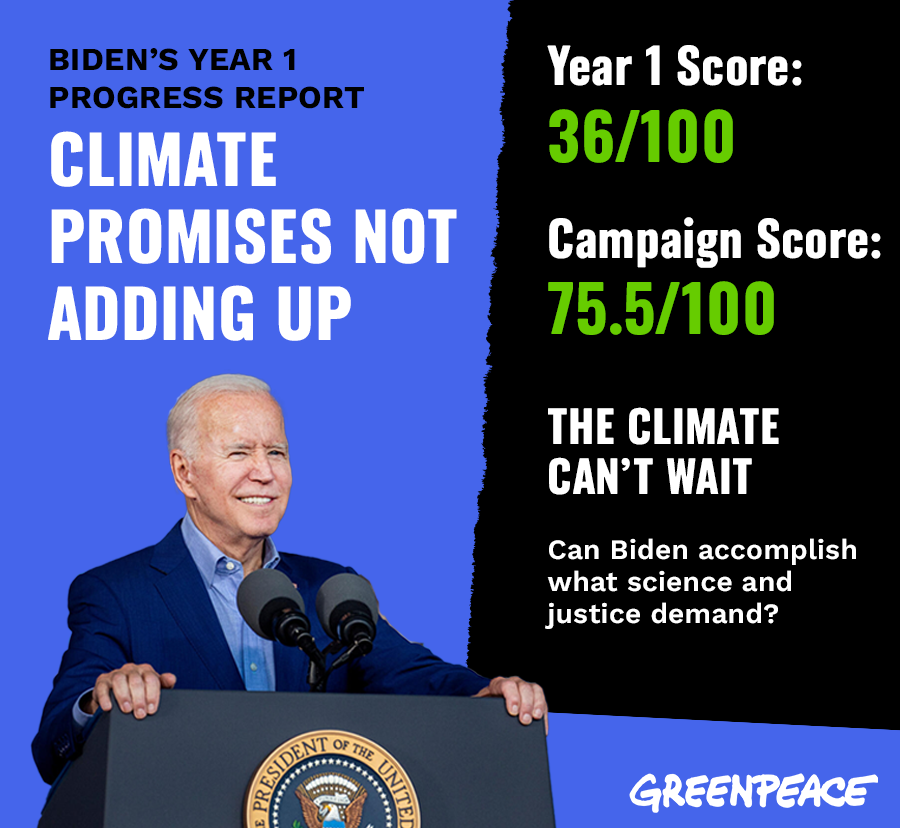

President Biden’s Year 1 Climate Progress Report

President Biden’s first year in office resulted in some victories for our communities and the climate, but there is work that remains unfinished and most initiatives lack the ambition to meet the demands of science and justice.

-

2021 Tuna Retailer Scorecard: The High Cost of Cheap Tuna

When Greenpeace USA published the first edition of Carting Away the Oceans (CATO) in 2008, not a single company out of the 16 major US retailers ranked on seafood sustainability received a passing score. Most of the companies surveyed had hardly given a thought to sustainable seafood; many had weak or non-existent policies, and commonly…

-

8 reasons why we need to phase out the fossil fuel industry

Fossil fuel corporations are profiting from the continued consumption of coal, oil and gas, which are driving global warming to dangerous levels. A Greenpeace report illustrated the need for managed…

-

The Climate Emergency Unpacked: How Consumer Goods Companies are Fueling Big Oil’s Plastic Expansion

As the climate crisis intensifies, there is growing worldwide acceptance of the need to slash greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the burning of fossil fuels to limit global heating to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels

-

All Hands on Deck – NOW! Key takeaways from the IPCC report on Physical Science Basis

Download Briefing Here

-

Dollars vs. democracy scorecard

Over the last year, hundreds of companies have made halfhearted attempts to appear socially conscious by releasing statements in support of voting rights and the Movement for Black Lives. In…

-

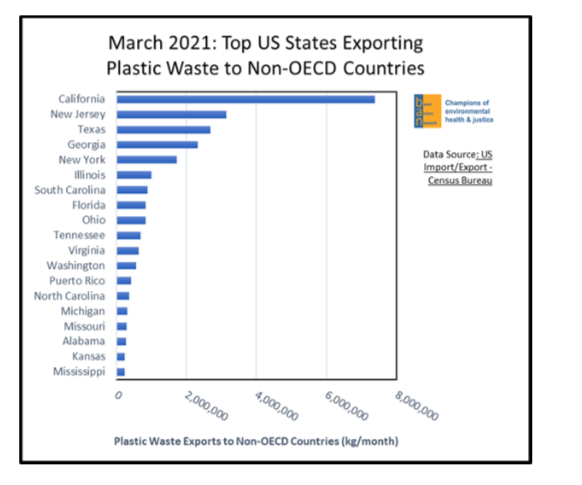

Acceptance of Unrecyclable Plastic Products and California’s Continued Exports of Plastic Waste Exports to Non-OECD Countries

To Statewide Commission on Recycling Markets and Curbside Recycling SUBJECT: Acceptance of Unrecyclable Plastic Products and California’s Continued Exports of Plastic Waste Exports to Non-OECD Countries The co-signers of this…

-

Fact Sheet: The Illegal Fishing and Forced Labor Prevention Act

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, a top threat to ocean ecosystems and global food security, is inextricably linked to human rights abuses at sea. Workers on fishing vessels around…

-

Greenpeace Report: Dollars vs. Democracy

A healthy democracy is a precondition for a healthy environment. When everyone’s vote counts and when everyone’s constitutionally-guaranteed right to peacefully protest…

-

Dollars vs. Democracy: Companies and the Attack on Voting Rights and Peaceful Protest

Dollars vs. Democracy is a new report from Greenpeace Inc., about how corporations contribute to the attacks on our freedom to vote and silence our right to dissent. Actions speak…

-

President Biden’s 100 Day Climate Progress Report

Numerical metrics are based on the following “progress bar” that represents steps toward full implementation, with weightings derived from the #Climate2020 Scorecard. Phasing Out Fossil Fuels 1. Lead a Managed Fossil…

-

High Stakes: The Impacts of Destructive Fishing

The Indian Ocean is a crucial ecosystem in the race to protect the high seas. From safeguarding marine biodiversity to promoting sustainable, socially responsible fishing, the changes needed to protect…

-

Fossil Fuel Racism: How phasing out oil, gas, and coal can protect communities

Fossil fuels — coal, oil, and gas — lie at the heart of the crises we face, including public health, racial injustice, and climate change. This report synthesizes existing research and provides new analysis that finds that the fossil fuel industry contributes to public health harms that kill hundreds of thousands of people in the…

-

Research Brief: Environmental Justice Across Industrial Sectors

A PDF version of this briefing is available here. Introduction The EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) provides data to the public regarding toxic air and water emissions from a large…

-

Comments Concerning the Ranking of Taiwan by the U.S. Department of State in the 2021 Trafficking in Persons Report

Publication Date: April 1, 2021 Author: GLJ-ILRF and Greenpeace on behalf of the Seafood Working Group This document contains the Seafood Working Group (SWG)’s comments concerning Taiwan’s ranking in the…

-

Programa de Recuperación Justa de Greenpeace USA

Volver a la normalidad no es una opción. El pasado no fue solo injusto y desigual, fue inestable. Lo que nosotrxs conocíamos como “normal” era una crisis. Debemos reimaginar los…

-

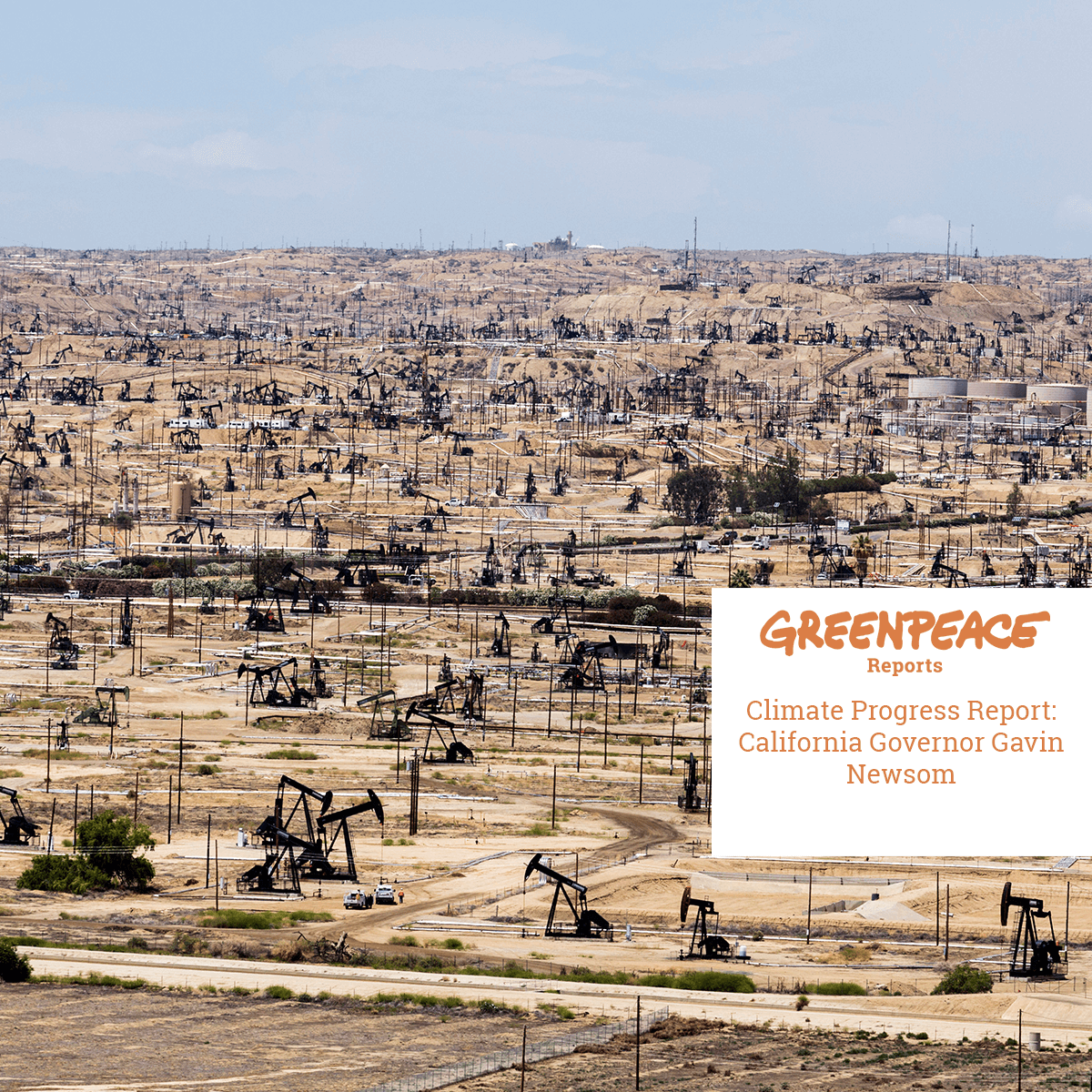

Climate progress report: California Governor Gavin Newsom

Based on his actions in 2020, Greenpeace is updating Gavin Newsom’s Climate Report Card to mark his performance on three core demands.

-

Fisheries Observers are Human Rights Defenders on the World’s Oceans

Fisheries observers are human rights defenders on the world’s oceans. These individuals work independently onboard commercial fishing vessels around the world to collect scientific data on the state of the…

-

Greenpeace USA’s just recovery agenda

We envision a world where everyone has a good life, where our fundamental needs are met, and where people everywhere have what they need to thrive.

-

Deception by the Numbers: Claims about Chemical Recycling Don’t Hold Up to Scrutiny

Despite decades of deceptive industry marketing, we know we can’t recycle our way out of the plastic pollution crisis. But the companies making and selling plastic—and their trade association surrogate,…

-

Reusables are doable

It is time to stop treating people and the planet as disposable. To save our climate and ensure healthy communities for everyone, we must end our reliance on cheap throwaway plastics.

-

Greenpeace USA Submission to the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis

In November 2019, Greenpeace USA submitted these recommendations to the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. Read the full submission here. Introduction Greenpeace USA appreciates the opportunity to inform…

-

Policy Briefing: Why the Department of Labor Must Put Taiwan-caught Tuna on its List of Goods Produced by Forced Labor

Last December, Greenpeace and 23 additional NGOs, trade unions, and businesses sent a letter to the US Department of Labor, Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) Office of Child Labor,…

-

Policy Briefing: Remediation of Orphan Oil & Gas Wells in COVID-19 Stimulus

A new policy briefing from Greenpeace USA calls on Congress to provide funding to close the backlog of orphaned oil and gas wells, strengthen policies around well bonding and retirement,…

-

Policy Briefing: Protecting Energy Workers and Communities in a Just COVID-19 Recovery

A new policy briefing from Greenpeace USA calls on Congress to create a national Worker and Community Protection Fund (WCPF) to support fossil fuel workers, their families, and impacted communities in…

-

Meet the Oil Executives Visiting the White House to Discuss ‘Relief’ for the Industry With Trump

Tomorrow, executives from at least seven US oil companies will meet with Donald Trump at the White House to discuss relief for the oil industry. As reported by the Wall…

-

The Making of an Echo Chamber: How the plastic industry exploited anxiety about COVID-19 to attack reusable bags

In a new research brief, Greenpeace USA details the ways the plastics industry is exploiting people’s fears around COVID-19. Through front groups, corporate-funded research, and misrepresentation of scientific studies, the…

-

Choppy Waters – Forced Labor and Illegal Fishing in Taiwan’s Distant Water Fisheries

DOWNLOAD THE REPORT Taiwan is one of the world’s largest distant water fishing (DWF) powers, with over 1,100 Taiwanese-flagged vessels fishing across our oceans and hundreds more Taiwanese-owned vessels flagged…

-

Greenpeace Sustainability, Labour & Human Rights, and Chain of Custody Asks for Retailers, Brand Owners and Seafood Companies

Greenpeace seeks a substantial transformation from fisheries production dominated by large-scale, socially and economically unjust, and environmentally destructive methods to prioritise smaller scale, community-based, labour intensive fisheries using ecologically responsible,…

-

Greenpeace Report: Carbon Impacts of Reinstating the U.S. Crude Export Ban

A policy briefing from Greenpeace USA and Oil Change International shows that reinstating the U.S. crude oil export ban could reduce global emissions by the equivalent of closing 19 to 42 coal plants.

-

“Anti-Greta” climate denier Naomi Seibt marched with Neo-Nazis and promotes white nationalism

What journalists and the climate movement need to know about the Heartland Institute’s new contractor and contrarian Youtuber, Naomi Seibt.

-

Report: Circular Claims Fall Flat

In a new Greenpeace report, a comprehensive survey of plastic product waste collection, sortation and reprocessing in the United States (U.S.) was performed to determine the legitimacy of “recyclable” claims…

-

Toxic Air: The Price of Fossil Fuels

A new report from Greenpeace Southeast Asia and the Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) found that air pollution from burning coal, oil, and natural gas accounts…

-

Policy Briefing: Carbon Impacts of Reinstating the U.S. Crude Export Ban

A new policy briefing from Greenpeace USA and Oil Change International calculates the climate benefits of reinstating the crude oil export ban. Download the full policy briefing here. Download the…

-

Report: The Smart Supermarket

A new Greenpeace USA report walks readers through The Smart Supermarket, a hypothetical store that has moved beyond single-use plastics and packaging. As retailers grapple with how to transition away…

-

Human Rights for Migrant Fishers

Abolish the Overseas Employment Scheme for Migrant Fishers and Expedite the Domestication of ILO Convention No. 188

-

Throwing Away the Future: How Companies Still Have It Wrong on Plastic Pollution “Solutions”

A Greenpeace USA report released today, Throwing Away the Future: How Companies Still Have It Wrong on Plastic Pollution “Solutions,” warns consumers to be skeptical of the so-called solutions announced…

-

The Two-Tiered System: Discrimination, Modern Slavery and Environmental Destruction on the High Seas

Greenpeace welcomes the opportunity to contribute to the Inaugural Plenary Meeting of the ILO SEA Forum for Fishers. The issue of discrimination in the global distant water fishing (DWF) industry…

-

Greenpeace Report: Packaging Away the Planet

The entire lifecycle of plastic production, use, and disposal is destroying our communities and environment.

-

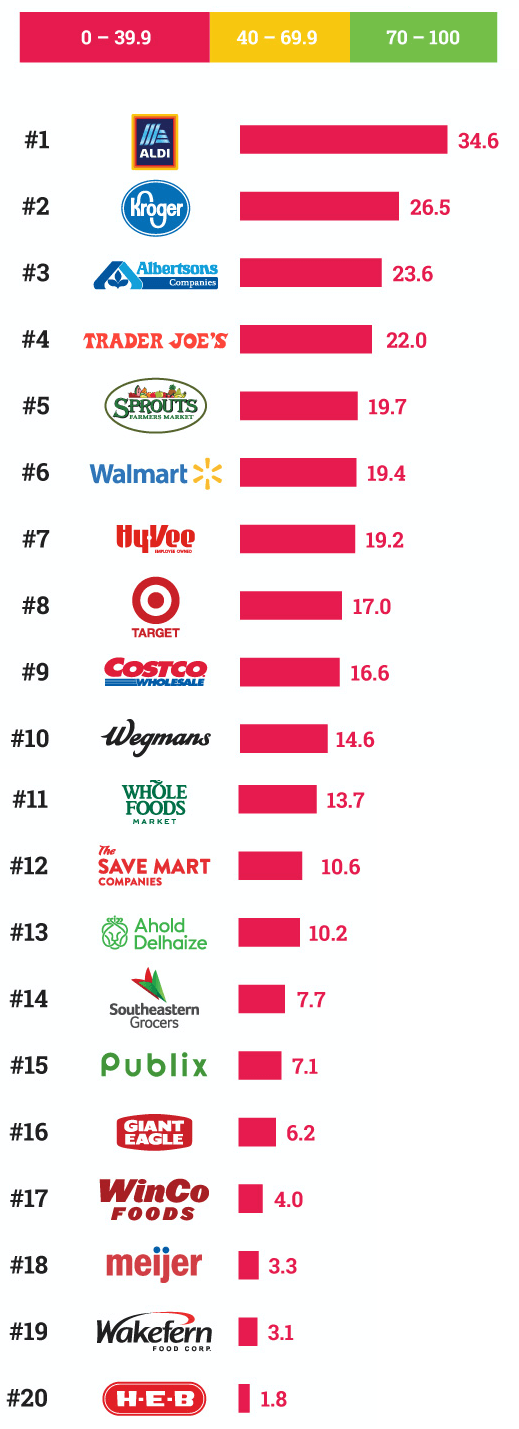

Packaging Away the Planet

Packaging Away the Planet evaluates 20 large U.S. grocery retailers for the first time on their efforts to eliminate single-use plastics. Across the board, supermarkets are failing to adequately address…

-

Greenpeace Report: Real Climate Leadership

The next president and Congress must adopt policies to phase out domestic fossil fuel production as part of any comprehensive climate policy effort like a Green New Deal. This fossil fuel phase out should occur in tandem with policies to boost renewable energy and ensure a just transition for workers, communities and tribal nations. This…

-

Meet the Fourteen House Members Who Pump Most Of Our Oil

Ten Republicans and four Democrats represent the parts of the country where the vast majority of U.S. crude oil is produced. As the 116th Congress gets down to work, we…

-

Greenpeace Report: Click Clean Virginia

San Francisco and “Silicon Valley” may first come to mind when imagining the home of big internet companies, but the physical beating heart of the internet…

-

Report: Protecting Science at Federal Agencies

A new report describes “new and ongoing threats to the use of science in public health and environmental decisions…

-

Greenpeace Report: Dangerous Pipelines

Executive Summary Enbridge, which is proposing to expand its Line 3 pipeline through Minnesota, has a long track record of pipeline spills, both chronic small spills and large…

-

Survey Briefing: Voices of Scientists at BOEM and BSEE

Download the full survey briefing here. Summary Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, working with the Union of Concerned Scientists and Iowa State University, sent a survey to 407 scientists…

-

Carting Away the Oceans 10

To view the report, click here. This 10th-anniversary edition of Carting Away the Oceans identifies which major supermarkets are leaders in sustainable seafood and which are falling behind. The findings are…

-

Greenpeace Report: Carting Away the Oceans

In June 2008, Greenpeace published the first edition…

-

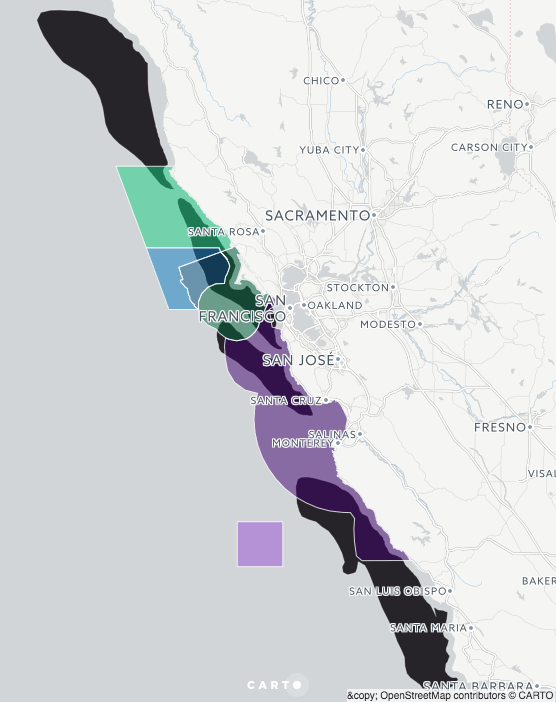

Greenpeace Report: Tar Sands Tanker Superhighway Threatens Pacific Coast Waters

Summary Results The proposed Trans Mountain Expansion Project (TMEP) would increase the number of oil tankers carrying tar sands from Vancouver, Canada through the Salish Sea and down the…

-

A Little Story About the Monsters In Your Closet

A new investigation by Greenpeace has found a broad range of hazardous chemicals in children’s clothing and footwear across a number of major clothing brands, including fast fashion, sportswear and…

-

Greenpeace Report: Too Far Too Often

“Too Far Too Often” details the unethical and inappropriate tactics employed by ETP and related companies against opponents of DAPL, and highlights how, in spite of increased global scrutiny and intense criticism of ETP’s tactics at Standing Rock to intimidate and quash opposition, ETP continues to apply many of the same tactics and to display…

-

Oil and Water: ETP & Sunoco’s History of Pipeline Spills

Click here to read the full report. Summary Results From 2002 to the end of 2017, ETP, Sunoco and their subsidiaries and joint ventures reported 527 hazardous liquids pipeline incidents…

-

Greenpeace Report: Contaminating the Courts

Corporations have increasingly begun to resurrect the legal strategy of expanding the concept of corporate personhood to argue that local, state, or federal environmental laws violate their constitutional rights. This trend isn’t totally new, but it has accelerated since the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United v. FEC decision.

-

Greenpeace Report: Oil and Water: ETP & Sunoco’s History of Pipeline Spills

Energy Transfer Partners and its complex network of subsidiaries and joint ventures owns one of the nation’s largest networks of natural gas, crude oil and petroleum products pipelines.

-

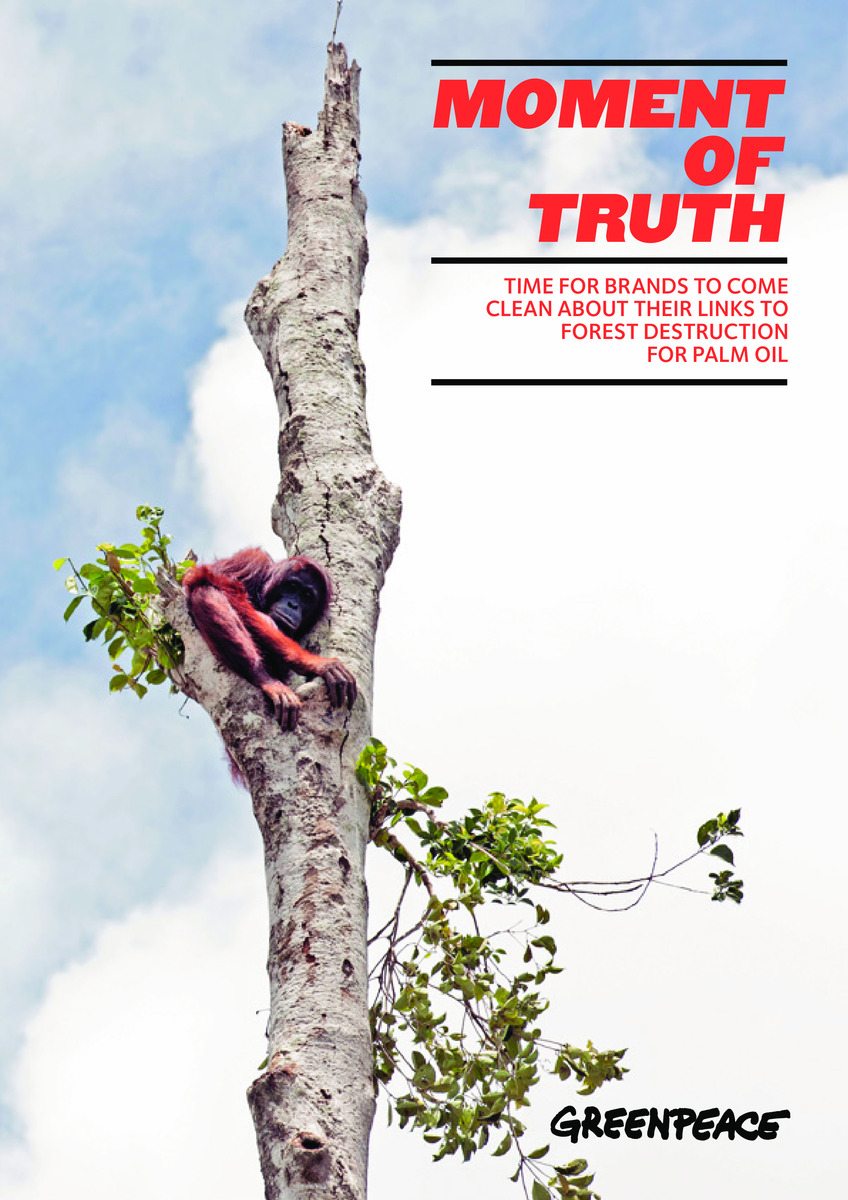

Moment of Truth: Time for Brands to Come Clean About Their Links to Forest Destruction for Palm Oil

It has been close to a decade since consumer brands pledged to eliminate deforestation from palm oil and other key commodities by 2020. Despite these commitments, there is growing evidence…

-

Problematic Pipelines: The many obstacles facing Keystone XL

Download the full investor briefing here. There are compelling reasons to question whether TransCanada Corporation should proceed with Keystone XL in the midst of federal and state legal challenges to…

-

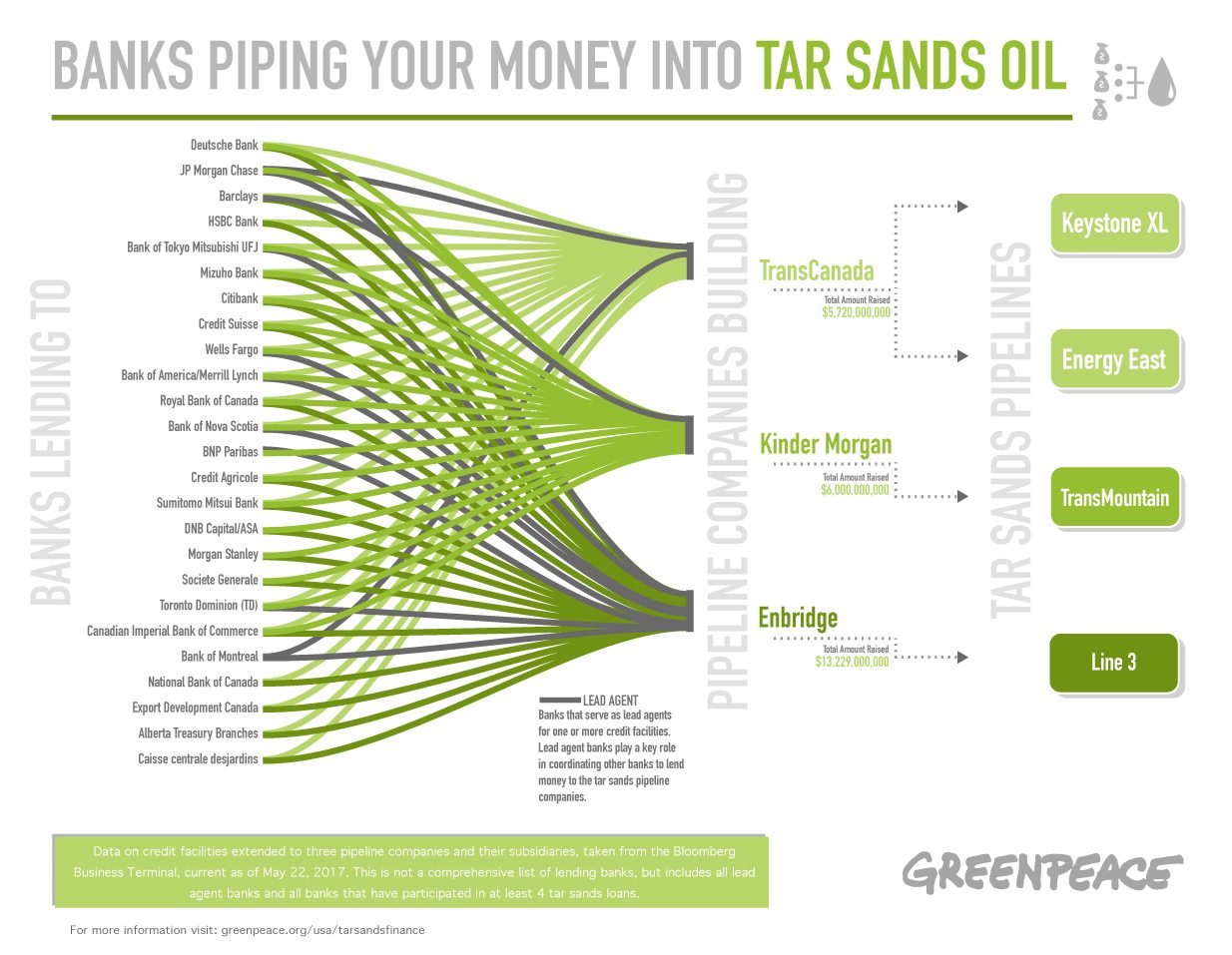

In The Pipeline: Risks for Funders of Tar Sands Pipelines

Download the full report here. Three major new tar sands pipeline projects are proposed: Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain Expansion, TransCanada’s Keystone XL and Enbridge’s Line 3 expansion. This report is…

-

Hurricane Harvey Air Pollution: Interactive Database

Click for full-page Hurricane Harvey Air Pollution Database. Scroll down for Methodology & References. Total Air Pollution Reported: 5,700,328 lbs Total of Most Hazardous Chemicals: 1,529,483 lbs 12 Companies Responsible for 90% Percent…

-

Beyond Fossil Fuels

You can see it in the vegetables growing in Arctic greenhouses, in wind turbines replacing diesel to power community microgrids, and in the spread of innovative educational initiatives. This future…

-

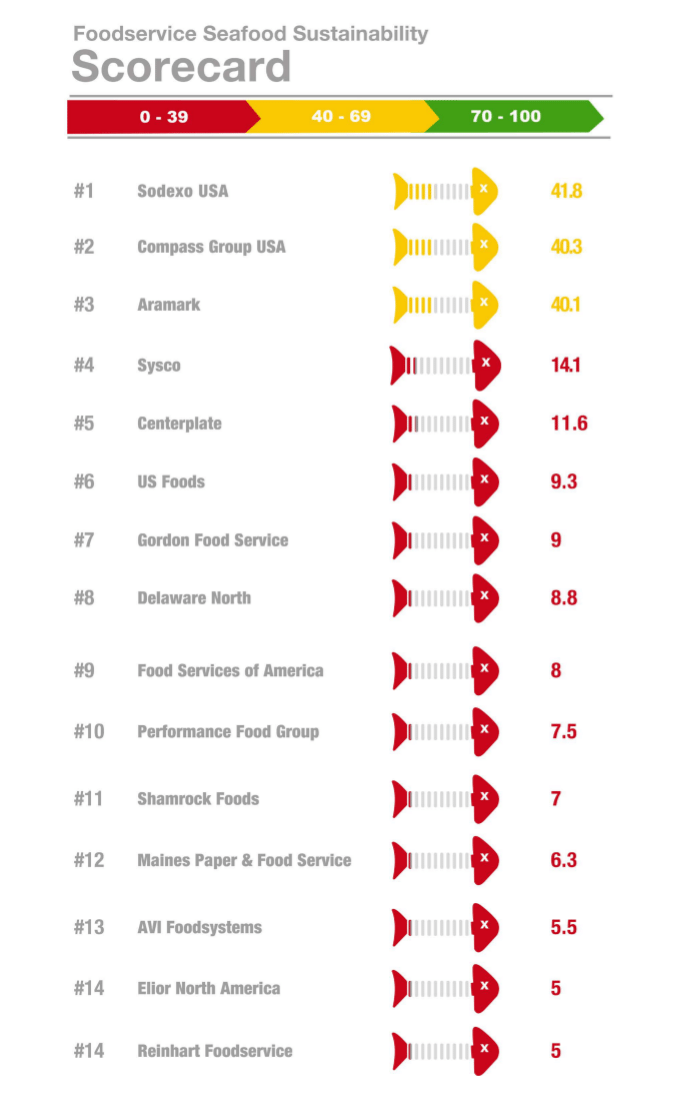

Sea of Distress 2017: The Foodservice Industry, Ocean Health, and Seafood Workers

Click here to download Sea of Distress 2017, Greenpeace’s second assessment of foodservice companies that feed millions of people every day who dine outside the home. Unfamiliar to many, companies…

-

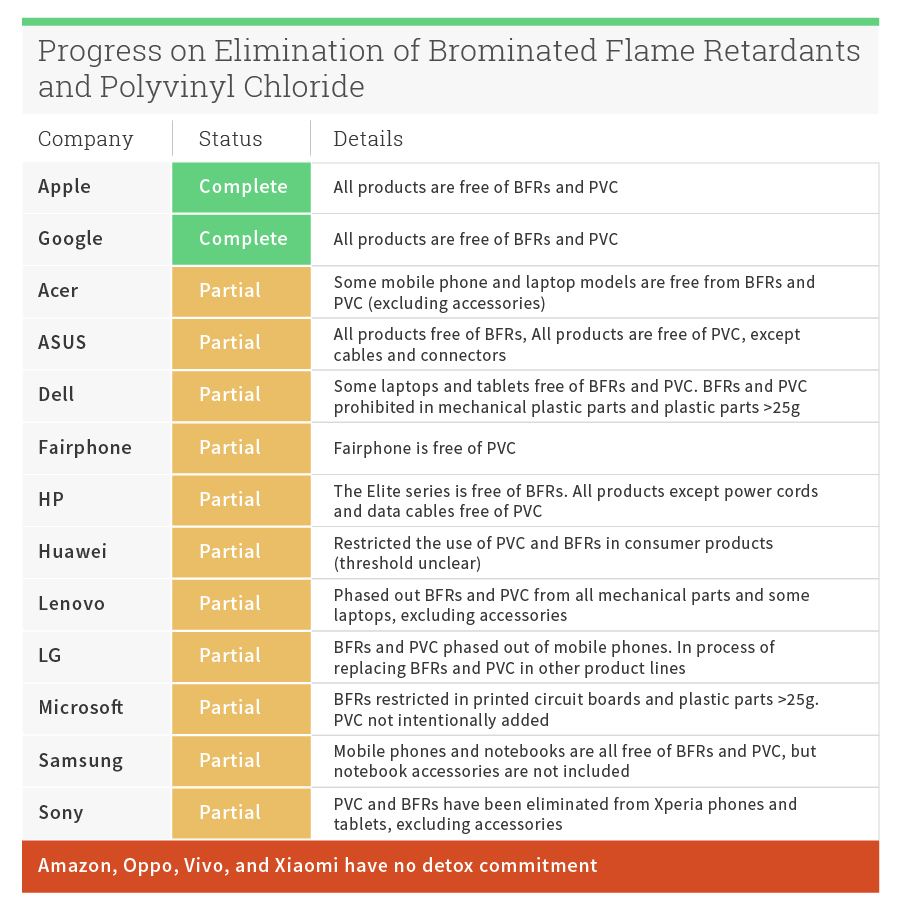

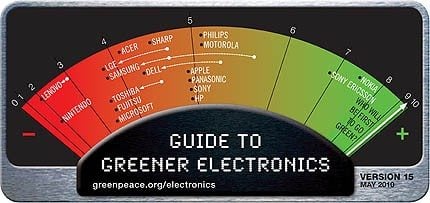

Greenpeace Report: Guide to Greener Electronics 2017

There is no question that smartphones, PCs, and other computing devices have changed the world and our day-to-day lives in incredible ways. But behind this innovative 21st-century technology lie supply…

-

Greenpeace Report: Guide to Greener Electronics 2017

The Guide to Greener Electronics is an analysis of what 17 of the world’s leading consumer electronics companies are doing to address their environmental impacts. Here’s how…

-

California National Marine Sanctuaries Under Trump Review Contain Sizable Oil and Gas Deposits

Summary Findings Expansions of National Marine Sanctuaries (NMS) off the California coast ordered by Presidents Bush and Obama are currently under review by the Trump administration. A geospatial analysis has…

-

4 Proposed Tar Sands Oil Pipelines Pose a Threat to Water Resources

Download the full analysis. Summary Findings: Oil spills anywhere pose serious risks to human health and the environment, and oil spilled into bodies of water is difficult to fully clean…

-

Tar Sands Pipelines Are Heavily Financed by 26 Key Banks

Twenty-six key banks are lending money to the companies building the following tar sands pipelines: TransCanada’s proposed Keystone XL pipeline Enbridge’s proposed replacement and expansion of the existing Line 3…

-

Policy Brief: Rex Tillerson Must Recuse Himself from the Keystone XL Decision

Download the Policy Brief. ExxonMobil stands to benefit from the U.S. State Department’s approval of the Keystone XL pipeline, and consequently Secretary of State Rex Tillerson should recuse himself from…

-

From Smart to Senseless: The Global Impact of Ten Years of Smartphones

Smartphones have undeniably changed our lives and the world in a very short amount of time. In 2007, almost no one owned a smartphone. In 2017, they are seemingly everywhere. Globally,…

-

Rex Tillerson’s Conflict of Interest in Guyana

nteger eget ipsum finibus, rhoncus enim at, consequat nulla. Morbi posuere posuere luctus. Proin a sodales turpis. Sed in tortor lobortis, finibus est ut, facilisis ante. Curabitur elementum ligula vestibulum…

-

Colorado’s “Raise the Bar” Ballot Initiative

“Raise the Bar” would make it harder for people to bring ballot measures up for a vote in Colorado. It is part of a multi-year oil and gas-funded campaign to…

-

A Deadly Trade-off: IOI’s Palm Oil Supply and Its Human and Environmental Costs

This Greenpeace International investigative report looks at the Malaysian palm oil company IOI Group and its downstream subsidiary in Europe and North America, IOI Loders Croklaan. Despite policies to ensure…

-

The Climate Change Costs of Offshore Oil Drilling

Download the full report — The Climate Change Costs of Offshore Oil Drilling. The Obama administration has proposed an expansion of offshore oil and gas leasing, with new lease sales…

-

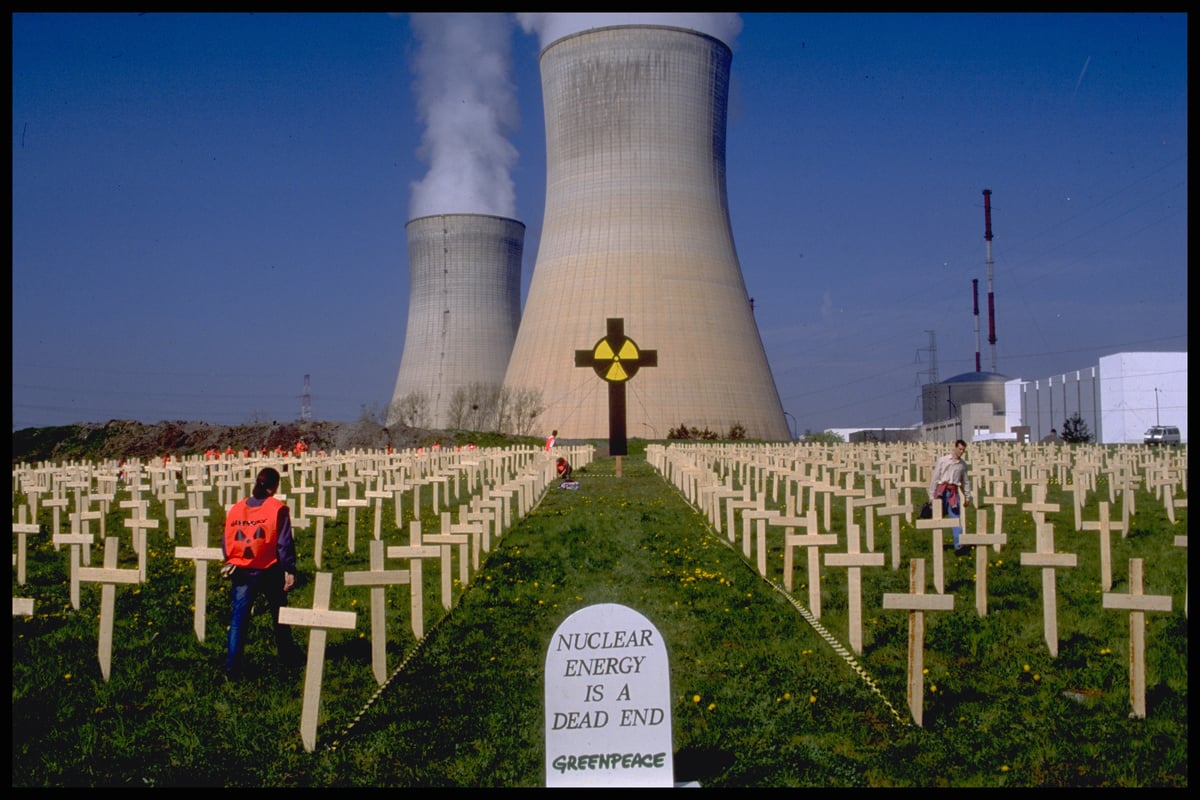

Nuclear Near Misses: A Decade of Accident Precursors at U.S. Nuclear Plants

Greenpeace has documented 166 near misses or accident precursors at U.S. nuclear power plants. Sixty one events and more than one hundred conditions were identified by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory…

-

Ray Hilborn: Overfishing Denier

Update, February 2019: Back in 2016, Greenpeace called out a well-known scientist named Ray Hilborn for failing to disclose the funding he’d received from the fishing industry in several of his…

-

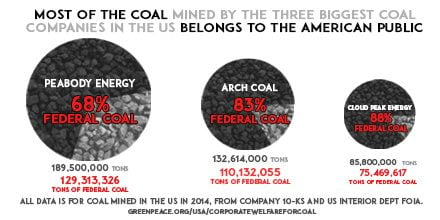

Corporate Welfare for Coal

Download the full report — Corporate Welfare for Coal: The biggest coal mining companies depend on subsidized federal coal, even as they attack federal climate and clean air policies The coal industry…

-

Cutting Deforestation Out of Palm Oil – Company Scorecard

Click here to download the full report: “Cutting Deforestation Out of Palm Oil.” In 2015, Indonesia was wracked by the worst forest fires for almost twenty years. The disaster, the…

-

Scientific Integrity Complaint Regarding Arctic Oil Drilling Environmental Impact Statement

Greenpeace, the Center for Biological Diversity, and Friends of the Earth submitted a complaint under the Department of the Interior’s Scientific Integrity Policy requesting an investigation into the loss of…

-

Chlorine Bleach Plants Needlessly Endanger Millions

Bleach manufacturers use chlorine gas to produce bleach and also repackage bulk chlorine gas into smaller containers for commercial use. These facilities often ship, receive and store their chlorine gas…

-

Supply Chained

The report features new interviews with survivors of trafficking and forced labour in Indonesia who faced abuse on Thai-operated fishing vessels. These ships transferred their tuna and other fish to…

-

Third Financial Quarter Coal Market Report: Risks to U.S. Coal Mining and Export Proposals (October 2015)

All prices are in USD unless otherwise noted. The information in the report is not financial advice, investment advice, trading advice or any other advice. This report was prepared by: Greenpeace, Sierra…

-

A Review of the Impact of Seismic Survey Noise on Arctic Wildlife

Firing seismic airguns to find new oil reserves in the Arctic Ocean is ‘alarming’ and could seriously injure whales and other marine life, according to a new scientific review. The…

-

Untouchable: The Climate Case Against Arctic Drilling

There is a clear logic that can be applied to the global challenge of addressing climate change: when you are in a hole, stop digging. If we are serious about tackling…

-

Coal Market Report – Risks to US coal mining and export proposals, July 2015

The US coal industry is facing structural decline and companies pursuing coal export proposals in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) are particularly at risk. This update highlights execution risks for PNW…

-

Carbon Capture SCAM

Supporters of carbon capture for oil extraction claim that oil produced with CO2 injection is going to get produced somewhere else anyway, and therefore would actually be ‘green’ oil because it keeps CO2 from…

-

Carting Away the Oceans 2015

Our Carting Away the Oceans report, released annually since 2008, identifies which major grocery chains are leaders in sustainable seafood and which are falling behind. The findings are telling. In…

-

Case studies: The impacts of extracting and burning natural gas

Numerous studies have shown that the processes of extracting and burning natural gas, including fracking, have grave environmental impacts. Here are a few of them.

-

Japan’s Nuclear Crisis

In the face of the continuing disaster, even Japanese Prime Minister Abe appears to be revising his position of 2013 that the situation at Fukushima is under control. The INES 7…

-

Fukushima Impact

The catastrophic nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, which began on 11 March 2011, not only crippled four of the reactors at the site, but also vividly…

-

Smart Breeding

Genetically engineered crops are very limited in sophistication, being almost completely dominated by herbicide tolerance and insect resistance traits. Could the numerous tools of biotechnology deliver better outcomes? This report tries to answer that question. Genetic engineering has an inability to deal with complex (multi-genetic) traits (often the ones most useful, such as increased yield)…

-

Kingpins of Carbon

Their strategy has aimed to (1) shrink, disable and paralyze progressive government and (2) manipulate the remaining levers of government power by (a) eliminating all restrictions on private money in…

-

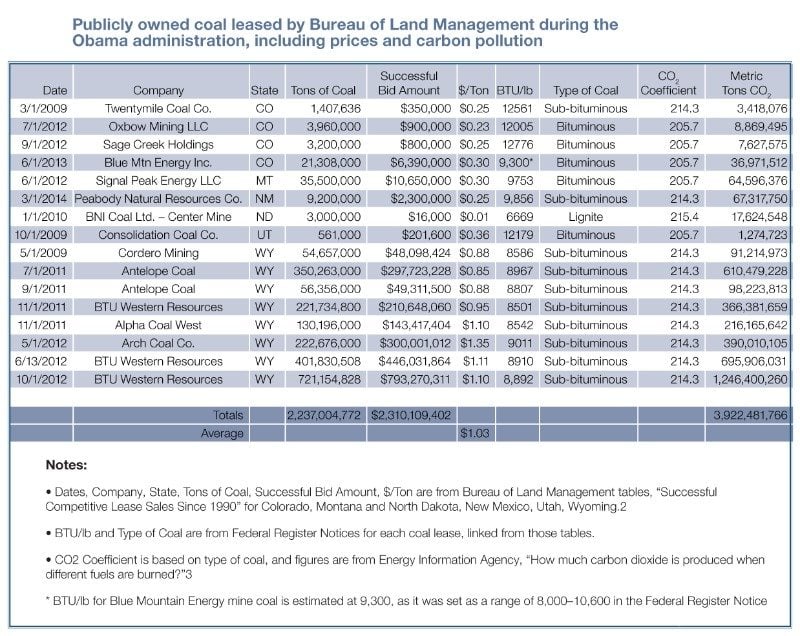

Leasing Coal, Fueling Climate Change

Download the PDF of “Leasing Coal, Fueling Climate Change” This question is especially important in light of a recent federal court ruling, which blocked plans to expand a coal mine…

-

Licence to Launder

The oil palm plantation being developed by Herakles Farms in the southwest region of Cameroon – an area of great biodiversity surrounded by five protected areas – illustrates what happens when irresponsible companies are not held accountable to local laws and processes. The companies activities pose a serious threat to forested areas and the communities…

-

Carting Away the Oceans 2014

Despite progress made by the retail sector overall, overfishing, destructive fishing, and illegal fishing are still major problems for ocean conservation and the economies of developing countries. Populations of the…

-

Energy Revolution 2014

The Energy [R]evolution aims to wean the economy off dirty fuels as thoroughly and quickly as possible, and in a way that is technologically, politically, and ecologically realistic. This report is…

-

Your Online World: #ClickClean or Dirty?

Clicking Clean: How Companies are Creating the Green Internet

-

A Little Story About a Monstrous Mess

Greenpeace has investigated the hazardous chemical residues present in children’s clothing. A set of 85 clothing items from Zhili Town of Huzhou in Zhejiang Province and Shishi in Fujian Province…

-

Logging: The Amazon’s Silent Crisis

Governance in the timber sector in the Brazilian Amazon is weak and open to exploitation, allowing criminals launder illegal timber as legal with official documentation. It is estimated that in…

-

Carting Away the Oceans 7

There is still a great deal of work to be done, but let’s take a minute to raise a glass in acknowledgement of some of the truly remarkable stories of…

-

Bees in decline

The next time you see a bee buzzing around, remember that much of the food we eat depends significantly on natural insect-mediated pollination — the key ecosystem service that bees and other pollinators provide.

-

Two Years after Fukushima, Duke Energy still making risky nuclear bets

Read More: Duke Energy’s risky nuclear bets

-

Herakles Exposed

The report details a series of 9 misstatements, lies, or inaccuracies found in communications from Herakles Farms around their palm oil project in Cameroon.

-

The Myth of China’s Endless Coal Demand

The US coal industry – reeling from sagging domestic demand, plummeting profits, and tanking stock prices – is desperate for a new market for its wares, and it thinks it has found one in China. But in reality, the Chinese market for US coal exports may dry up before major new US coal shipments ever…

-

Herakles Farms in Cameroon

The project covers 73,086 hectares (180,599 acres) of forest and existing farmland and is home to an estimated 14,000 people, mostly small farmers. Residents are fiercely opposing the plantation, fearing…

-

Donors Trust: Laundering Climate Denial Funding

Findings: Donors Trust and its associated organization, Donors Capital Fund, have funded 102 climate-denial organizations since 2002. From 2002 to 2011, Donors Trust and Donors Capital Fund have provided $146…

-

Palm Oil’s New Frontier

When it is done well and is properly managed, palm oil production can be of potential benefit to the populations of developing countries, providing sustainable livelihoods. On the other hand,…

-

Junking the Jungle

Greenpeace research has tracked a number of these products back to Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), a company that continues to rely on rainforest clearance in Indonesia. By purchasing paper…

-

Driving Destruction in the Amazon

Two years of Greenpeace investigations, summarized in this report, reveal that end users including major global car manufacturers – indirectly or directly source pig iron whose production is fueled by…

-

Apple Clean Energy Road Map

The following analysis updates our evaluation of Apple to account for its recent clean energy announcements, and outlines the additional steps Apple should take to fulfill its laudable ambition to set a new bar with a “coal-free” and 100% renewably-powered iCloud. Greenpeace International is rescoring Apple now because of its recent ambitious and public commitments…

-

Carting Away the Oceans VI

Through varying combinations of progressive policy development, public support for conservation measures, and the elimination of unsustainable seafood inventory items, these two companies – Safeway and Whole Foods – have…

-

Protecting the Canyons of the Bering Sea

Situated between Alaska and Russia, Zhemchug and Pribilof canyons—both larger than Arizona’s Grand Canyon—cut into the slope along a several-hundred-mile stretch of the continental shelf break that is so productive…

-

Fukushima Nuclear Crisis

On 11 March 2011 a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck off the coast of Japan, followed by a tsunami that slammed the country’s eastern coast, destroying communities and taking the lives…

-

The Ramin paper Trail

A year-long investigation by Greenpeace International demonstrates that Asia Pulp & Paper (APP) is breaking Indonesian law, driving Sumatran tigers and ramin trees closer to extinction, and undermining CITES –…

-

Fukushima Nuclear Crisis Timeline

Documents the natural, social and political developments of the disaster

-

Toxic Koch: Keeping Americans at Risk of a Poison Gas Disaster

In 2010, Koch Industries and the billionaire brothers who run it were exposed as a major funder of front groups spreading denial of climate change science and a key backer of…

-

Greenpeace Analyzes the Lewis Powell Memo: Corporate Blueprint to Dominate Democracy

Forty years ago, not only was Greenpeace formed, but a then-obscure corporate lawyer (later appointed by President Nixon to the Supreme Court) drafted a memorandum for the U.S. Chamber of…

-

Lessons from Fukushima

It was a failure of human institutions to acknowledge real reactor risks, a failure to establish and enforce appropriate nuclear safety standards and a failure to ultimately protect the public…

-

The Lewis Powell Memo: Corporate Blueprint to Dominate Democracy

Forty years ago today, on August 23, 1971, Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., an attorney from Richmond, Virginia, drafted a confidential memorandum for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that describes a strategy for the corporate takeover of the dominant public institutions of American society.

-

Polluting Democracy

The majority of the ancient US coal fleet has not installed easily available technology that could reduce mercury pollution by 90%. Coal combustion is responsible for most US mercury pollution.…

-

How Clean is Your Cloud?

How much energy is required to power the ever-expanding online world? What percentage of global greenhouse gas emissions is attributable to the IT sector? This report takes a look at the energy choices some of the largest and fastest growing IT companies are making, as the race to build “the cloud” creates a new era…

-

Deepwater Horizon – One Year On

He further announced research to assess the feasibility of offshore drilling in theBeaufort and Chukchi seas off the north coast of Alaska.

-

Koch Industries: Still Fueling Climate Denial 2011 Update

Koch Industries: Still Fueling Climate Denial (2011 Update) Greenpeace released the report Koch Industries: Secretly Funding the Climate Denial Machine in March, 2010 garnering international media attention. In August, The…

-

Carting Away the Oceans V

While the oily gleam of sardines, mackerels, and other small, rapidly-growing fish in wetcase ice is becoming more common, most seafood merchants continue to focus on large, predatoryfish such as…

-

Chernobyl field findings – 25 years later

In March 2011, a Greenpeace research team visited several places in Rivnenska and Zhytomyrska Oblast, Ukraine, to collect samples of food products produced in those areas and which comprise a…

-

Fukushima – INES scale rating

Hirsch’s assessment, based on data published by the French government’s radiation protection agency (IRSN) and the Austrian governments Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics (ZAMG) found that the total amount…

-

Protection Money

I am confident that we can reach this goal [of GHG emissions reduction targets], while also ensuring sustainable and equitable economic growth for our people.

-

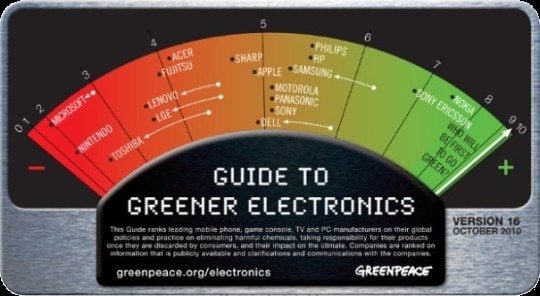

Guide to Greener Electronics – Version 16

While some of the top electronics manufacturers are failing to keep their environmental commitments, others are innovating and making significant gains in phasing out toxic chemicals, increasing energy efficiency, and…

-

Papua New Guinea not ready for funding for REDD

Download the report

-

Sinar Mas pays ‘ITS Global’ to greenwash its dirty laundry

Sinar Mas has since hired the Australia-based consultancy ITS Global (International Trade Strategies Global) to ‘assess the validity and accuracy of the claims’ made by Greenpeace ‘based on the evidence…

-

![Quit Nuclear Power – Invest in the Energy [R]evolution](https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-usa-stateless/2024/11/3e250054-gp1sx16j.jpg)

Quit Nuclear Power – Invest in the Energy [R]evolution

These goals are both possible to achieve at the same time.

-

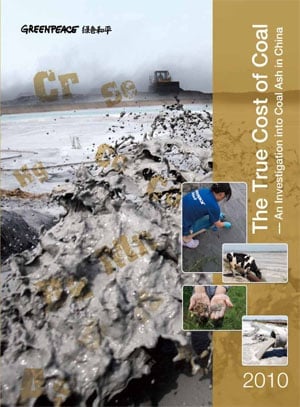

The True Cost of Coal – An Investigation into Coal Ash in China

In 2009 alone, China generated at least 375 million tons of coal ash – more than twice the amount of urban domestic waste produced in the same time period. Coal…

-

Greenpeace Security Inspection Report

The facility also has up to 7.6 million lbs of chlorine gas on site that could endanger a similar or larger population in the case of a catastrophic release. It…

-

Rice, Biodiversity & Nutrients

What happened to the rice landraces during the ‘Green Revolution’? There are few sectors in agriculture where the so-called Green Revolution had such an overwhelming impact as in rice production.

-

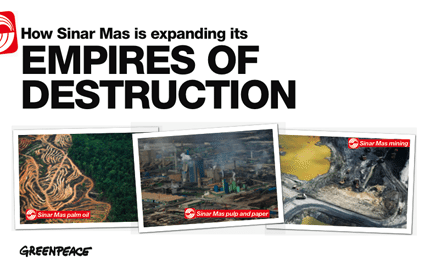

How Sinar Mas is expanding its empires of destruction

Sinar Mas group is notorious for its destruction of millions of acres of Indonesian rainforest, peatland and wildlife habitat. Two divisions within the group lead the destruction: pulp and palm…

-

![Greenpeace Energy [R]evolution 2010](https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-usa-stateless/2024/11/4496f0b9-energy-rev-250px.jpg)

Greenpeace Energy [R]evolution 2010

Download document

-

Mahogany – The “Green Gold” of Amazon Destruction

Download document Num. pages: 0

-

Shell’s Frontier Discoverer—The Next BP Deepwater Horizon

Download document

-

Offshore disaster: Timeline of offshore oil drilling, spills, and regulations

As the Gulf of Mexico oil spill continues to capture headlines around the globe due to its massive size and potential impact, it is useful to look back at the…

-

Dealing in Doubt

Dealing in Doubt (pdf) was authored by Cindy Baxter in 2013. The report describes organized attacks on climate science, scientists and scientific institutions like the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate…

-

How dirty is your data?

“How Dirty Is Your Data?” is the first ever report on the energy choices made by IT companies including Akamai, Amazon.com (Amazon Web Services), Apple, Facebook, Google, HP, IBM, Microsoft,…

-

Taking Stock of Tuna

Tuna is the world’s favorite fish. It can be found from high-end sushi restaurants in Tokyo to family shopping trolleys in North American supermarkets and the dinner plates of Pacific island communities. With the world’s appetite for tuna now greater than what our oceans can sustain, tuna stocks globally are coming under pressure, suffering from…

-

Koch Industries: Secretly Funding the Climate Denial Machine

Download report: Koch Industries: Secretly Funding the Climate Denial Machine (2010) Executive summary: Koch Industries has become a financial kingpin of climate science denial and clean energy opposition. This private, out-of-sight…

-

Green Gadgets: Designing the Future

There is an increasing demand for greener, longer-lasting electronic devices, and the industry has shown progress is possible. When companies apply their know-how and innovative spirit, change can happen, from…

-

Nuclear Reactor Hazards, Ongoing Dangers of Operating Nuclear

A comprehensive assessment of the hazards of operational reactors, new ‘evolutionary’ designs and future reactor concepts and the risks associated with the management of spent nuclear fuel, this report describes…

-

Nuclear Power: a dangerous waste of time

The nuclear power industry is attempting to exploit the climate crisis by aggressively promoting nuclear technology as a “low-carbon” means of generating electricity. Nuclear power claims to be safe, cost-effective,…

-

Slaughtering the Amazon

Download document Executive summary: Zero deforestation is a climate imperative Forests play a vital role in stabilizing the world’s climate by storing large amounts of carbon that would otherwise contribute…

-

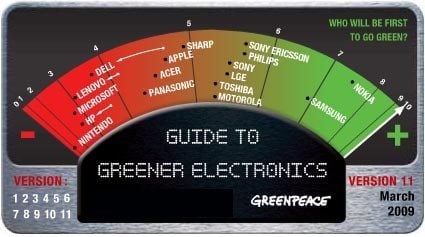

Guide to Greener Electronics – March 2009

The Greener Electronics Guide is our way of getting the electronics industry to take responsibility for the entire life cycle of its products. We want it to face up to…

-

Green Electronics: the search continues…

The results of the Green Electronics Survey 2008.

-

SINAR MAS : Indonesian Palm Oil Menance

Download document Num. pages: 4

-

![Energy [R]evolution: A Sustainable USA Energy Outlook](https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-usa-stateless/2024/11/60533cde-energy-r-evolution-a-sustai.jpg)

Energy [R]evolution: A Sustainable USA Energy Outlook

Download document

-

Amazon Cattle Footprint

Download document Num. pages: 16

-

Amazon Cattle Footprint, Mato Grosso: State of Destruction

Download document Executive summary: Cattle ranching is the primary driver of forest destruction in the Brazilian Amazon, with 79.5% of deforested land used for cattle pasture. Using specialized techniques to…

-

Amazon Deforestation Agreement

Download document

-

The True Cost of Coal

Traditionally considered the cheapest fuel around, the market price for coal ignores its most significant impacts. These so-called “external costs” manifests themselves as damages such as respiratory diseases, mining accidents,…

-

China after the Olympics: Lessons from Beijing

Download document

-

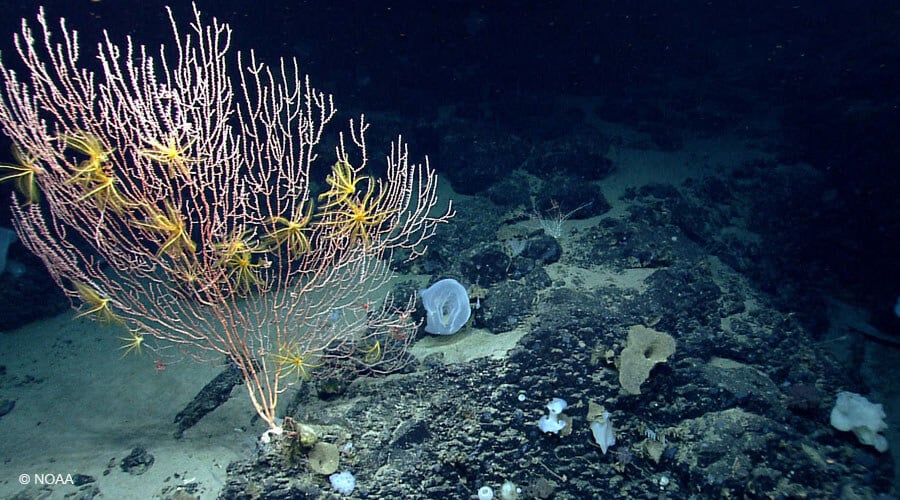

Pushed to the Brink: The oceans and climate change

It is a matter of serious concern that the oceans are being systematically degraded and are in decline. The most immediate and significant threat to the oceans is overfishing and…

-

Canned tuna’s hidden catch

Download document

-

Chemical contamination at e-waste recycling and disposal sites in Accra and Korforidua, Ghana

The global market for electrical and electronic equipment continues to expand, while the lifespan of many products becomes shorter.

-

Playing Dirty

Analysis of hazardous chemicals and materials in games console components.

-

Food Security and Climate Change: The Answer is Biodiversity

Climate change will profoundly affect agriculture worldwide.

-

Greenpeace investigation: Japan’s stolen whale meat scandal

A four-month-long undercover investigation by Greenpeace uncovers some of the whaling industry’s dirtiest secrets — including embezzlement of whale meat from the taxpayer-subsidized program.

-

How Unilever palm oil suppliers are burning up Borneo

New evidence shows expansion by Unilever palm oil suppliers is driving species extinction in Central Kalimantan, and fueling climate change.

-

Executive summary – Turning Up the Heat : Global Warming and the Degradation of Canada’s Boreal Forest

Download document Executive summary: Executive summary Canada’s Boreal Forest is dense with life. Richly populated with plants, birds, animals, and trees; home to hundreds of communities; and a wellspring…

-

Greener Electronics Fujitsu-Siemens Ranking – 7th Edition

Download document

-

Taking tuna out of the can

Tuna is one of the world’s favorite fish. It provides a critical part of the diet for millions of poor people, as well as being at the core of the…

-

Trading Away Our Oceans

Instead of pursuing further liberalization, states should ensure existing international law is implemented fully and establish new rules to ensure sustainable and equitable management of the high seas. Furthermore, developing…

-

![Energy [R]evolution 2010 Executive Summary](https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-usa-stateless/2024/11/e8727821-energy-rev-250px.jpg)

Energy [R]evolution 2010 Executive Summary

The threat of climate change demands nothing short of an Energy Revolution–a transformation that has already started, as renewable energy markets exhibit huge and steady growth. In the first global…

-

Greener Electronics Fujitsu-Siemens Ranking – 6th Edition

Download document

-

Endangered Forests Definition: The Wye River Process

Download document

-

Greener electronics LG Electronics ranking: Fifth Edition

Download document

-

Greener electronics Fujitsu-Siemens ranking: Fifth Edition

Download document

-

Carving up the Congo – Executive Summary

Download document

-

Carving Up The Congo – Part 1

Download document

-

Carving Up The Congo – Part 2

Download document

-

Carving Up The Congo – Part 3

Download document

-

Carving Up The Congo – Part 4

Download document

-

Eating Up the Amazon

Download document

-

An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and Its Implications for US National Security

A world thrown into turmoil by drought, floods, typhoons. Whole countries rendered uninhabitable. The capital of the Netherlands submerged. The borders of the US and Australia patrolled by armies firing into waves of starving boat people desperate to find a new home. Fishing boats armed with cannon to drive off competitors. Demands for access to…

-

An Investigation of Factors Related to Levels of Mercury in Human Hair

Cover Letter: Download document Num. pages: 1 Executive Summary Hair analysis provides a historical record of an individual’s exposure to mercury or methylmercury. In this study hair analysis of mercury…

-

Liquid Natural Gas: A roadblock to a clean energy future

Executive Summary Over the past few years, fueled by rising natural gas prices, some of the world’s largest multinational corporations began searching for new sites for Liquid Natural Gas (LNG)…

-

Forest Crime File: Danzer Group (Revised 2nd Edition)

Download document

-

Impacts of climate change on glaciers around the world

Download document

-

Nuclear Incident at the Davis Besse Power Plant

Documents regarding the fifth-most dangerous nuclear incident in the United States since 1979:

-

Finding Chemo – Toxic Childrenswear by Disney

Executive Summary The results show clear differences in the chemical content of the finished garments. The bad news is that most prints contained high levels of one or other of…

-

Clean Energy Now! Campus Guide

Download document

-

Eco-Certification in the Forest Industry

Download document

-

Denial and Deception: A Chronicle of ExxonMobil’s Efforts to Corrupt the Debate on Global Warming

Throughout the last decade, ExxonMobil has been viewed internationally as the number one company driving the ongoing industry campaign to derail the international agreement to solve global warming.

![Energy [R]evolution](https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-usa-stateless/2018/10/631a4a40-climate-activist.jpg)

![Energy [R]evolution – Introduction](https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-usa-stateless/2024/11/41c1685d-gp0stpta1.jpg)